INDEPENDENT

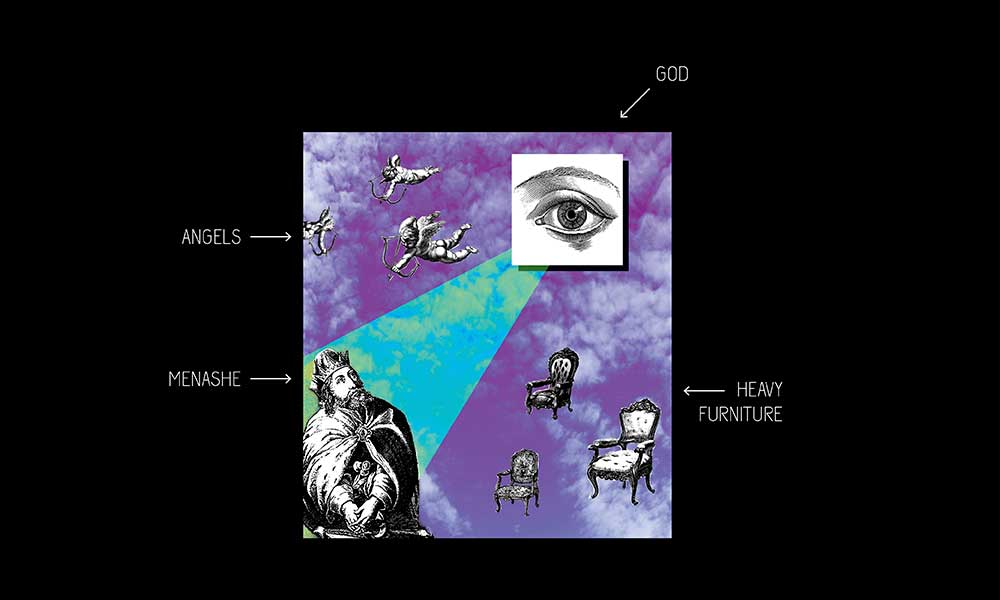

The most unforgivable king in Jewish history was Menashe, son of Hezekiah, who led his kingdom into idolatry. As they carried him off to Babylon in chains, he desperately turned to God for forgiveness. But the angels blocked the heavens with heavy furniture and nailed in extra boards to prevent that mamzer’s plea from being heard. What did God do? While the angels were engaged in choir practice, He bored a tiny hole in the boarded-up heavenly floor so that He could hear Menashe’s plea (Midrash Devarim Rabbah 2:20).

But that’s God’s thing. For us mere mortals, it depends. If someone accidentally bumps a cart into you in the supermarket, you can forgive instantaneously. On the other hand, if someone bumps you with an SUV, you may not be so quick to forgive as they fit your legs, hip and nose with prosthetics—because you’re human, and you hope he loses all of his teeth except one, and that one has a toothache! However, if we do transcend our mortality and forgive the sins committed against us by others, “God in turn will dismiss our sins” (Talmud Bav’li, Rosh Hashanah 17a).

Rabbi Gershon Winkler

Jewish Chaplain, Patton State Hospital

Patton, CA

HUMANIST

Few people have never been mistreated or hurt others. Jewish tradition makes demands of both parties. If we’ve hurt someone, we are required to seek rapprochement, prompted by sincere teshuvah, the recognition of our misdeeds, alongside our resolve not to re-offend. Conversely, when we’re hurt by someone who has sought forgiveness following genuine teshuvah, we are asked to forgive. In most human interactions this is the best path to reconciliation. Humanistic Jews recognize the wisdom of this. Whether through love, empathy or the knowledge that forgiveness is necessary for us to move on, we generally endorse efforts to extend it to others. We realize that the way to a better world is solely a human endeavor, one that must certainly include reconciliation.

But what about those who do not offer remorse, or whose misdeeds are simply too monstrous to forgive? Here, there are no clear answers—in Judaism or in Humanistic teachings. Even a belief that the world requires reconciliation cannot impose a duty to forgive. Ultimately, the decision must be left to individuals as we balance costs and benefits to ourselves and others.

Rabbi Jeffrey Falick

Birmingham Temple Congregation for Humanistic Judaism

Farmington Hills, MI

RENEWAL

It depends on what we mean by “forgive.” Jewish law deemed some acts so heinous that only death atoned, and then only with repentance (Yoma 86a; Hilchot Teshuvah 1:1). And even then, how can we absolve genocide, murder, sex crimes, child abuse and life-destroying lies?

But “forgiveness” isn’t absolution. We can “forgive” even if someone doesn’t deserve it—because we ourselves deserve the peace that can come by releasing pain and grudges. That’s forgiveness. It doesn’t absolve wrongs or withhold justice, but helps us live resiliently amid brokenness. It’s among our most powerful spiritual tools—and sometimes difficult to use.

Consider the 2015 Charleston church shooting—domestic terrorism targeting innocents. The triggerman confessed to wanting a race war. How does anyone “forgive” that? But the victims’ families found the inner power to forgive—not to inhibit justice, but to seek peace for themselves. Such forgiveness evokes grace—in Hebrew, chein, one of the Thirteen Attributes of God’s self-revelation to Moses after he shattered the first tablets on seeing the Golden Calf (Exodus 34:6). Grace can’t be deserved: It’s a spiritual gift we receive because we are. And this same God of chein was also a God of justice. We can forgive in that same way—in God’s grace, after the shattering, to seek peace.

Rabbi David Evan Markus

Temple Beth El

City Island, NY

RECONSTRUCTIONIST

Most forgiveness is partial. Our lives are lived on slippery slopes, in gray zones. Tradition posits a hypothetical rasha gamur, entirely evil person, and tzadik gamur, entirely righteous one—with 36 of the latter mythically roaming around. But the rest of us are in between—maybe perched right on the fulcrum, where our next altruistic or selfish act could tip the entire personal and cosmic scale. We’ve all done “unforgivable” things, and we’ve all been at least partially forgiven, with further chances to yet make good. Consider climate change: Carbon from the gas I burned driving to visit the sick endures in the atmosphere “even unto the third and fourth generation.” Endangered species, coastal dwellers and our own grandchildren can scarcely “forgive” us for our short-sighted emissions and slowness to change—yet every positive change measurably moves the needle, limits further suffering and bends the arc (slightly yet truly) back toward sustainability and justice. In short: Can we be fully forgiven for past sins? No, some damage done is permanent. Should we move forward, measuring our deeds, trying harder, doing better? Heck yes. That’s the gift of these coming holidays; Shanah Tovah.

Rabbi Fred Scherlinder Dobb

Adat Shalom Reconstructionist Congregation

Bethesda, MD

REFORM

Only a wronged person can grant forgiveness, so only he or she can answer. One might consider three questions. First: When wounded physically, spiritually, psychologically or materially by another, we must face the basic humanity of that person with all their faults, failings, prejudices and imperfections. Jewish tradition recognizes that we all have flaws and make mistakes. No matter how egregious the wrong, are we ready to see the wrongdoer’s humanity?

Second: Has justice been served? According to Jewish law, it is appropriate to ask for recompense from the wrongdoer. This may be as simple as a sincere apology, or it may involve facing legal or material consequences for one’s actions. We should not be cruel by withholding forgiveness from those who have made amends.

Third: how might forgiving or withholding forgiveness help me? The Talmud’s rabbis noted the social, emotional, spiritual or even health benefits of forgiveness; we should too. If we find ourselves wrapped in clouds of stress, resentment, anger or intolerance, then finding a way to move toward forgiveness would be to our benefit.

Rabbi Dr. Laura Novak Winer

Fresno, CA

CONSERVATIVE

Jewish tradition instructs us to forgive those who have wronged us if they make restitution and apologize. If they don’t, each individual has to decide the limits, if any, of forgiveness.

Eva Mozes Kor, who died in July at age 85, challenged me to think about this question. Kor was in Auschwitz and was among the 1,500 sets of twins upon whom the Nazi doctor Josef Mengele conducted horrific experiments. Kor publicly forgave those who had tortured her and all who had participated in the genocide. When I first learned of this, I was shocked that a survivor could forgive any Nazi, ever. I do not think one person could or should absolve all those who participated. And I do not like the public nature of Kor’s behavior. But I now recognize a certain wisdom in Kor’s action. One forgives not to ease the offender’s conscience but to let go of the anger and hurt. Never to forgive is ultimately to allow those who wronged us to continue hurting us. It hurts only the victim.

As for forgetting—we really can’t. There’s no delete button for the brain. We don’t forget the pain, we just learn to live with it.

Rabbi Amy Wallk Katz

Temple Beth El

Springfield, MA

MODERN ORTHODOX

I am very resistant to the idea of any sin being beyond forgiveness. I would like to think that given God’s loving nature and “compassion for all of God’s creatures” (Psalms 145:9) no bad action is beyond being overcome by God’s infinite goodness. However, in sins between one human being and another, the Talmud says that God won’t forgive unless/until the sinner regrets and repents, returns what was stolen or damaged and wins forgiveness from the victim. For murder, there can be no forgiveness, because the victim cannot be made whole or asked for forgiveness.

The Holocaust struck me as unforgivable, and for 50-plus years, I would never buy a German product nor set foot in Germany, lest my actions profit one of the perpetrators. In the late 1990s, I told myself that those who had carried out this monstrous crime were mostly gone, and children should not be punished for the (unforgiven) sins of their fathers (Deuteronomy 24:16). I relaxed my boycott and traveled to Germany for a conference on Jewish-Christian relations. It helped that the German government had taken responsibility for the Shoah and paid significant reparations (albeit no amount of money can make whole the losses). Germany had also become the most dependable, supportive ally of Israel in Europe out of a sense of accountability for Nazi crimes. This does not constitute forgiveness. But it paves the way for new generations to work together to prevent recurrences of the unforgivable sin.

Rabbi Yitzhak Greenberg

Riverdale, NY

ORTHODOX

The Talmud speaks lovingly about the power of forgiveness; it’s not mandatory, but almost. When people are asked, they should do the right thing and forgive. But there are two caveats. Forgiveness is not a pro forma declaration of “OK, you’re forgiven.” It means the person actually forgives—which is not so easy to do. Also, the Talmud says certain things do not demand forgiveness. After physical injury—some commentators extend this to emotional injury—it may still be admirable to forgive if asked, but the expectation is not there.

The Talmud says God Himself cannot forgive transgressions between people. If Reuven harms Shimon, and Reuven repents sincerely but doesn’t ask Shimon to forgive him, God cannot grant that forgiveness. In a famous incident recounted by Simon Wiesenthal in The Sunflower, Wiesenthal, a prisoner in the camps, was called to an infirmary where an SS officer lay dying. The officer wanted to confess and ask forgiveness for his crimes against Jews. In his last moments, he asked Wiesenthal to forgive him, as a surrogate for the Jewish people. Wiesenthal exited the room. He subsequently wrote that while he felt the urge to forgive, those who were actually in a position to forgive were not there, so he couldn’t do it.

Rabbi Yitzchok Adlerstein

CrossCurrents

Los Angeles, CA

SEPHARDIC

There are! But they are not the same for everyone. One person might be unable to forgive parental apathy, but another might empathize with the apathetic parent. That latter person might not forgive a child who escaped from home, while the first one will forgive and embrace even his own child who did so.

If we search for an objective answer, we should first ask if regret was expressed. If not, forgiving is more like letting go of a grudge and forgiving oneself. If regret was expressed, we should ask: 1. Was the apology sincere? 2. Would others of my culture and upbringing consider the act an offense? (If the person committing the offense might see it differently, maybe there’s room for forgiveness.) If most people would agree it was an offense, and you feel it is unforgivable, then it should not be forgiven. I think most people would agree that crimes such as murder, rape, sexual assault or criminal negligence that caused irreparable damage to body or soul fall in this category. True, there are programs that bring together victims’ relatives and murderers, which reportedly provide some closure for the relatives and generate remorse. But the relatives can forgive only for what they have endured, not for what the victim has suffered. Finally, some crimes should not be forgiven, by individuals or society, to deter potential criminals.

Rabbi Haim Ovadia

Potomac, MD

CHABAD

“What is crooked will not be able to be straightened, and what is missing will not be able to be counted” (Ecclesiastes 1:15). Some misdeeds have severe, irreversible effects and are seemingly beyond forgiveness. At the same time, at the core of Judaism is forgiveness. We are taught to emulate G-d and forgive, just as G-d is all-forgiving.

How do we reconcile these apparently contradictory ideas? We sometimes find ourselves in situations where the betrayal and pain are so great that we are justified in not forgiving. At those times, we need to remember the saying that “Not forgiving someone is like drinking poison and expecting the other person to die.”

Forgiveness does more for the provider than the recipient. It does not magically make the pain go away, but it allows one to move past the hurt and begin healing. Not forgiving amplifies the consequences of a misdeed and perpetuates its negative effects. Better to forgive and move on to a brighter future than hold on to an unforgivable offense and be stuck in a dark past.

Rabbi Simcha Backman

Chabad Jewish Center of Glendale and the Foothill Communities

Glendale, CA

If murder is unforgivable, then Moses and King David are unforgiven. David Berkowitz, the mass murderer, is in life imprisonment (last I heard) and has been forgiven by God for his murders. If he can be forgiven, then can’t we all be? Of course, as in his case, it requires repentance. In the New Testament, Jesus equates hatred in the heart with murder. That includes just about all of us. As they say, to err is human, to forgive divine. It takes a spiritual transformation to receive that “Divine forgiveness.”

First.. I don’t know what the word ‘SIN”‘ is, means or anything … I know the transgression definition, but that is too vague.. Forgiveness ???? I’m sorry ?… , restitution ?? meaningless phrases..

forgiveness is forgiving yourself … not for the transgressed

Forgiving murderers is called misplaced compassion there is no forgiveness for evil people!!

Can God save someone convicted of treason by the government? Can they be forgiven and go to heaven?