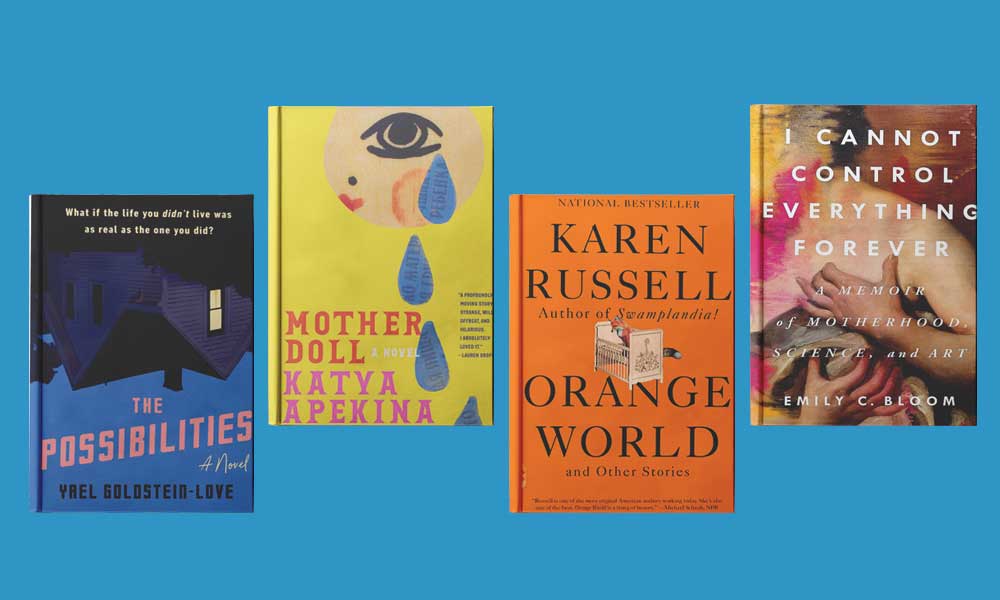

The Possibilities

by Yael Goldstein-Love

Random House, 304 pp.

Mother Doll

by Katya Apekina

Overlook Press, 320 pp.

Orange World and Other Stories

by Karen Russell

Vintage Contemporaries, 288 pp.

I Cannot Control Everything Forever: A Memoir of Motherhood, Science and Art

by Emily C. Bloom

St. Martin’s Press, 352 pp.

Zhenia, a Los Angeles-based aspiring actress who’s the protagonist of Katya Apekina’s Mother Doll, is having a rough pregnancy. Her husband Ben, unready for fatherhood, has left her; worse, her long-dead Russian Jewish great-grandmother, Irina, has contacted her from the Other Side through a medium and insists on long phone calls in which she shares the story, previously unknown in the family, of how she abandoned Zhenia’s beloved grandmother Vera at age 5 in an orphanage in revolutionary Russia. As the pregnancy progresses, so does the haunting; soon Irina has jumped the telephone wires to take up residence in Zhenia’s apartment, and Zhenia, having given birth, must juggle care of her newborn son with the aggressive ghost competing with him for attention and breast milk.

Zhenia has it easy compared with Hannah Bennett, the central character in Yael Goldstein-Love’s The Possibilities, the mother of an eight-month-old son named Jack who nearly died at birth in a difficult Cesarean. He came so close, in fact, that Hannah is tormented by flashes of a false memory in which a solemn nurse carried the still, blue baby away from her across the delivery room. Is she experiencing normal postpartum anxiety and ambivalence (and exasperating her husband Adam, “a goy from Ottawa” who likes things logical), or is there a parallel universe in which her baby died and that split off from hers, multiverse-style, in the moment of crisis? The question would be theoretical, but the alternative timeline seems somehow to be threatening Jack’s safety. It’s hard enough to parent a newborn in one universe; Hannah, it seems, must navigate millions.

What is it about motherhood, especially early motherhood, that has been propelling novelists lately toward the surreal and the supernatural? Is it the exhaustion, the intensity, the seemingly sky-high stakes of every moment’s choice? Or just a backlash from the apple-pie centuries, when the only acceptably shared feelings about bearing and rearing children (from the mother’s point of view, anyway) were best expressed with hearts and flowers? Those centuries seem increasingly distant at a time when the political discourse, post-Dobbs, understandably stresses notions of pregnancy and motherhood as states so intense and costly to the mother that forcing a woman to undergo them should be unthinkable. (Despite a recent spatter of conservative commentary suggesting that narratives like this suggest a feminist aversion to motherhood, I’d say these kinds of depictions, far from condemning the experience, are just giving it its due.)

What is it about motherhood, especially early motherhood, that has been propelling novelists lately toward the surreal and the supernatural?

Whatever the cause, you can take your pick of recent novels—particularly, though not exclusively, by writers who are also Jewish mothers—that portray motherhood not only as a raw and primal experience (leaky incisions, leaky breasts, sleeplessness, obsessive fear, obsessive love) but as one that is so intense and extreme that it breaks the bounds of realist fiction to encompass monsters, demons and other odd visitations. These aren’t genre thrillers or supermarket Gothics, either, but mainstream literary works by established novelists; they make claims to say something true about life, and they deliver. To do justice in serious fiction to the reality of having a baby under a year old, apparently, you need a touch of the impossible.

For Zhenia, in Mother Doll, the supernatural dimension flows from her relationship with her grandmother, Vera, who has helped raise her while barely remaining civil with her own daughter, Zhenia’s mother Marina. (When an interviewer with the online magazine Kveller asked Apekina about her “obsession” with “intergenerational matrilinear trauma,” the novelist responded, “That is my beat, for sure.”) Zhenia knows her husband hates the idea of having a child, but she can’t give up on the (unplanned) pregnancy. “You’re disappearing and this baby is appearing,” she tells the comatose Vera over the phone, “and the two feel connected to me.”

Part of the delight of these wacky stories is the way they plumb the near-unconscious memories of something that strained reality at the time.

Vera dies soon after. Alas, it’s not she but the spectral great-grandmother, Irina, who makes her presence known when Zhenia goes into labor: “Zhenia felt like her body was becoming a portal and something deep inside was being pried apart. ‘Not just my cervix, but like, something in another dimension.’” And it’s Irina’s presence that has to be resolved, first by Zhenia taking in the full, catastrophic story of Irina’s maternal failure and what happened between her and Vera, and then, more concretely, through a purely physical, hilariously motherhood-flavored form of exorcism.

Irina’s tormented self-questioning about whether she did the right thing for her child—so intense that it allows her to bridge the gap from the dead to the living—is echoed in the passionate emotions that power Hannah’s travels between worlds in Goldstein-Love’s The Possibilities. Is it good old Jewish-mother guilt, that notoriously powerful force, or something more purposeful? At first, Hannah is merely preoccupied with the false memory that Jack died at birth. Then, when he disappears from his crib, those feelings merge with a conviction that it’s all her fault: “I was aware that it made no sense…there couldn’t possibly be any connection between my missing child and what my insurance reimbursement claims called adjustment disorder with postpartum onset and Adam called Jewish Mother Overdrive and I called the car-swerve feeling,” the sense that she could dip at any moment into a baleful alternate reality. “Fear was my mother tongue,” she muses, “but this level of fear right now, these past eight months, every second since the moment Jack was born…was something altogether different, something that broke open the rules of how the world worked.”

That kind of fear, which most parents will recognize without difficulty, becomes the force on which Hannah “rides the possibilities” from world to world, seeking a Jack who seems sometimes lost to her, sometimes close enough that her milk leaks. To find him, she has to sink deep into the intense physicality of motherhood, “breast milk, spit-up, soiled diapers; shrieks of displeasure that felt like the world ending, that I myself would end if I couldn’t soothe his fury and his pain; a little mouth sucking voraciously, skin against skin, wet and devouring, a confusing swirl of annihilation and contentment.” As with Zhenia, a big part of the answer turns out to be intergenerational, with Hannah’s own impaired and absent mother becoming her guide through the dimensions. Another piece of it is the surreal blending of identities that can make the mother/baby dyad in real life so destabilizing to the sense of reality.

You don’t actually need to look to supernatural fiction for evidence of that feeling. A straightforward version turns up in a new nonfiction memoir by literary scholar Emily C. Bloom about learning to tend to her diabetic and hearing-impaired baby: “Motherhood…is itself an experience that troubles the distinction between self and other.”

The maternal-surrealism genre has been building for a while. I first noticed it in a non-Jewish context when my New Yorker feed served up a short story that first ran in 2018, Karen Russell’s “Orange World” (later anthologized in a volume of the same title). The haunted new mother in this case is Rae, who was told during pregnancy that she had a high statistical risk of a negative genetic outcome, panicked, and made a deal with a creature she believed to be the devil. The baby was born healthy, so Rae is stuck serving the devil, and serve him she does. Anything to protect her child.

Rae isn’t Jewish, probably, and as Jewish mothers go, these other mothers aren’t particularly Jewish, either—when asked whether she’ll circumcise her new son, Zhenia in Mother Doll responds, “No, people don’t do that anymore”—but in one sense they embrace a view of motherhood that’s bound up in Jewish culture, the idea of the mother not as an angel in the house but as a sometimes terrifying bastion of strength and toughness. That stereotype may have been the butt of a generation of Jewish comedians, but these novels are in communication with it, albeit from the other side of the equation. Philip Roth’s nightmare Jewish mother isn’t someone you’d want to be, but you wouldn’t mind having her on your side if you got stuck between universes, or in an unfortunate contract requiring you to breastfeed the devil.

And community and female solidarity—admitting the unspeakable, facing it, drawing support from other beleaguered mothers—turns out to be the final element that saves these moms from the supernatural menaces with whom, or which, they’ve become entangled. When Hannah needs to “ride the possibilities” to the scariest emotional place of all, where she can connect with her lost mother, she asks her babies-and-new-moms group to sit with her and hold her hands—and they do, not even asking her to explain. The funniest moment in “Orange World” is when Rae finally admits to Yvette, an older, more experienced mom in her support group, that she’s not just having “trouble with night feedings,” as she said in the sharing circle; actually, she’s sneaking out every night at 4 a.m. to crawl into a gutter and nurse a satanic rodent. She “watches Yvette’s face and awaits her reassignment, from weary stranger to dangerous lunatic,” but instead “a look of naked exasperation flashes across [Yvette’s] carefully made-up face and she responds, ‘That fucking thing. It’s been coming south of Powell?’”

It turns out that the junior-grade devil lies in wait for any member of the support group whose fear for her child has become sharp enough so that she’s willing to bargain. Having mutually fessed up, the moms band together for an exorcism—this one, in line with the suburban surrealist vibe, involves a minivan and a cat carrier.

I once asked a woman I think of as one of the ultimate Jewish mothers—a rabbi, no less, who raised five boys—what the early years had been like. “To be honest,” she replied, “I don’t really remember a thing about it.” Every mom I’ve quoted this to has laughed with recognition. Part of the delight of these wacky stories is the way they plumb the near-unconscious memories of something that strained reality at the time. It’s taken literature a while to catch up with the idea that “motherhood” is an experience undergone by terrified human beings in all their quirkiness, not a sentimental abstraction.

So mighty is the Jewish mother stereotype laid atop this abstraction that it’s a surprise to find what lurks beneath when it’s peeled away. In fact, the fears and truths here resonate well with the Jewish mother’s understanding of the world: The world is a scary place, a narrow bridge over profound insecurity and uncertainty, and having children in it is the scariest thing of all; moms are strong, and if necessary they can fight demons and monsters and the laws of physics; moms are on a hero quest that verges on the improbable. And when it all seems too much, and reality and parenting are too hard to bear, the best way to get through it is coming together with your community.

Amy E. Schwartz is Moment’s opinion and book review editor.