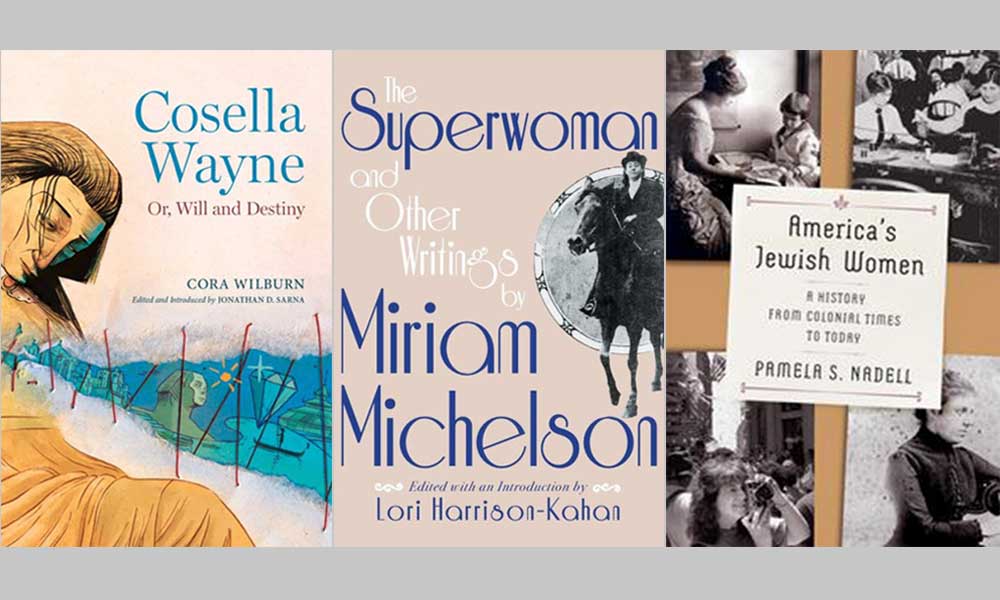

Cosella Wayne: Or, Will and Destiny

By Cora Wilburn

Edited and Introduced by

Jonathan D. Sarna

U. of Alabama Press, 336 pp, $29.95

The Superwoman and Other Writings

By Miriam Michelson

Edited with an Introduction by

Lori Harrison-Kahan

Wayne State U. Press, 400 pp, $36.99

America’s Jewish Women: A History from Colonial Times to Today

By Pamela S. Nadell

W. W. Norton, 336 pp., $17.95

The larger-than-life figure of Wonder Woman strode back into popular culture in 2017 in the person of Gal Gadot, her red, white and blue costume augmented by gold power-bracelets and a weaponized gold tiara, thrilling Jews around the world with her unmistakable Israeli accent. She seemed like a completely new type of feminist hero, and a Jewish one to boot. The former Israel Defense Forces soldier, transformed into a universal superhero—with a professional day job, no less—may be the most telegenic Amazonian yet to conquer Western culture.

But in fact, neither the concept of a utopian, feminist superhero nor her connection to Jewish heritage is a new development. It only seems that way because the real-life women who imagined such figures or inspired their creators have been forgotten, their adventures and accomplishments unrecorded—like so many women throughout history. The original 1940s-era creators of Wonder Woman, William Moulton Marston and his two female companions, his wife Elizabeth Marston and their joint life partner Olive Byrne, were inspired by a wide constellation of female achievers and rule-breakers: by the characters in late 19th- and early 20th-century feminist novels, by female political activists such as Planned Parenthood founder Margaret Sanger, and by the unorthodox living arrangements in their own home and in that of several friends. The Marstons and Byrne projected from their own experience a world in which gender roles and responsibilities did not need to be completely traditional. Little did they know, however, that many of the qualities they wished society to emulate had been lived and pioneered by some remarkable American Jewish women whose stories are only now coming to light.

Two new books revive such forgotten women, both of whom could be considered feminist Jewish superheroes in their own right. Lori Harrison-Kahan, who teaches English at Boston College, trains her spotlight on the muckraking journalist and novelist Miriam Michelson, who fought for progressive causes and penned a utopian novel about “superwomen” at the turn of the 20th century. Even more improbably, Brandeis historian Jonathan D. Sarna has restored to us the writer/adventurer Cora Wilburn—as it turns out, the first Jewish American novelist—whose forgotten 1860 cliffhanger, Cosella Wayne: Or, Will and Destiny, is a hair-raising tale of a Jewish woman’s adventures in a largely unfamiliar world.

Sarna rediscovered Cosella Wayne in the archives of the publication in which it was originally serialized, a spiritualist journal of the era called Banner of Light: A Weekly Journal of Romance Literature and General Intelligence. He has also extensively researched its author’s life, augmenting the novel with a scholarly introduction. Sarna describes the detective work that led to his discovery of Wilburn and his amazement upon identifying a novel depicting Jewish life written nearly half a century before American Jewish fiction was thought to have commenced. Its author shattered preconceptions in other ways as well. Born in Europe in 1824 as Henrietta Pulfermacher, Wilburn led a life that defied convention—she traveled the world, suffered (and wrote about) abuse at the hands of her father and converted briefly to Catholicism.

A rich, vibrant melodrama, the story follows protagonist Cosella (whose initials echo the author’s) through a checkered life as she is stolen as a baby and undergoes countless trials and tribulations. Readers accustomed to more contemporary writing may need to adjust to Wilburn’s prose, which, true to its era, delights in excessive adjectives and gender and other stereotypes, and which often channels the dreamlike imagery of the spiritualist movement that inspired the author. The fictional Cosella’s action-packed life and her confrontations with scurrilous characters rival the most colorful travel narratives of Jewish men writing in America, Germany, Prague and elsewhere in the 19th- and 20th-century world. What might have been a dismal, dystopian reflection on the challenges confronting Jewish women instead becomes—with a little magic transcendentalist dust—a triumph for its female Jewish unmarried heroine.

Nearly as obscured by time are the life and career of Miriam Michaelson, a successful journalist and fiction writer who chronicled Jewish and gender issues in the American West. Born in 1870, she spent most of her life in California; although not traditionally observant, she was interested in the West Coast Jewish community. Literary scholar Harrison-Kahan has done an important service in collecting some of Michelson’s best short stories, her most fascinating and controversial journalism and her 1912 feminist utopian novella The Superwoman in a single volume. The novella tells the story of the hapless Mr. Wellburn (a cognate for “well-born”), a shipwrecked millionaire and ladies’ man who is rescued by members of a female-dominated, pre-modern utopia. His adventures lack subtlety—as Wellburn angrily defends his entitled lifestyle and conventional notions—but they provide food for thought.

In her collected journalistic pieces, painstakingly excavated by Harrison-Kahan from a variety of publications, Michelson’s coverage of such contemporary issues as women’s suffrage, the fight for Hawaiian independence, the transformation of modern marriage, race and class tensions, women’s role in the national economy, and even transgender rights is a bracing entrée into the complex and sometimes openly contentious politics of the era’s progressive causes. She exposes the rivalries, anti-Semitism and racism of many advocates in those movements, although she occasionally carries her own prejudices into the ring as well. Her greatest personal rivalry adds a fascinating coda about late-19th-century female social commentators: She alternately skewers and admires the work of Charlotte Perkins Gilman, author of the pioneering text Women and Economics, the chilling short story “The Yellow Wallpaper” and the feminist utopian novel Herland. The last of these titles, sometimes cited as an inspiration for Wonder Woman’s Amazonia, finds its twin in Michelson’s The Superwoman, although the two books were supposedly published without knowledge of each other.

Neither the concept of a utopian, feminist superhero nor her connection to Jewish heritage is a new development.

Harrison-Kahan introduces us not only to Michelson’s strikingly modern life and career but also to the social and political issues of the day, many of which remain timely. She sets Michelson alongside other unconventional examples of Jewish women in the same region—from Rachel (Ray) Frank, the so-called “girl rabbi” who, though not ordained, preached from Western pulpits throughout the 1890s, to Josephine Sarah Marcus Earp, the Jewish wife of famed lawman and gunslinger Wyatt Earp, who lived (often on the run) in the Wild West of the late 19th and early 20th century. The examples of such women stretch the boundaries of many popular images not only of women but also of Jews, but they have been mostly forgotten.

Fortunately, a spate of recently published novels, short stories, biographies, collections of vintage newspaper articles and scholarly works have revived interest in the study of American Jewish women’s lives and work. Jewish women writers in particular are being studied more, following decades of scholarly focus on the well-known Jewish male writers who monopolized not only American Jewish but all American writing in the mid-to-late 20th century.

Michelson and Wilburn are only two of many examples. New scholarship is also filling in the context around them: Pamela S. Nadell’s 2019 America’s Jewish Women: A History From Colonial Times to Today amasses the stories of myriad American Jewish women, addressing their lives, creativity and activism across the generations, from Colonial New Yorker Abigail Levy Franks to poet Emma Lazarus, from labor leader Clara Lemlich to Second Wave feminist author Betty Friedan.

Nadell includes many women who had been virtually unknown—testament not just to the author’s tenacity, but to the scholarship that has expanded the field in recent years. From a handful of scholars a mere 40 years ago, American Jewish women’s history today boasts scores of published books, journal articles, conferences and doctoral dissertations and has sparked the rediscovery of literature written by Jewish women in English, Yiddish, Hebrew, Spanish and other languages. And the internet has expanded the accessibility and size of the most extensive resource in Jewish women’s history to date, the online Jewish Women’s Encyclopedia published by the Jewish Women’s Archive (jwa.org), which already has more than 2,200 biographical entries and is currently being expanded for a major relaunch.

In her classic essay “Why Have There Been No Great Woman Artists?” the late art historian Linda Nochlin posed a sardonic rhetorical question, highlighting a deeper problem. The answer, of course, is that there have been many important, pioneering and, yes, great women artists—and that their lack of recognition teaches us more about society’s limited imagination than about the artists themselves. The same is true in abundance about women writers, including those who have lived and written about American Jewish women’s experiences. Sweatshop girls, journalists, world travelers, politicians, suffragists, stage performers and even brothel madams are being brought to life as we watch. The aggregate of their work and biographies should ensure that we never again encounter the indefensible answer to Nochlin’s question: “Because they didn’t exist.”

Lauren B. Strauss is a professor of modern Jewish history and literature at The American University in Washington, DC.

Moment Magazine participates in the Amazon Associates program and earns money from qualifying purchases.