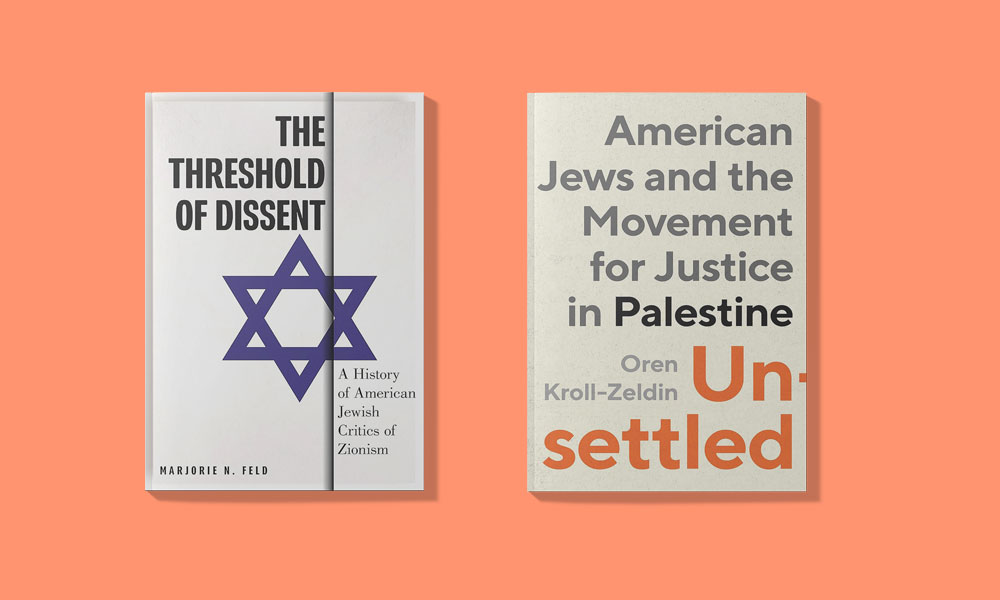

The Threshold of Dissent: A History of American Jewish Critics of Zionism

By Marjorie H. Feld

New York University Press. 288 pp.

Unsettled: American Jews and the Movement for Justice in Palestine

By Oren Kroll-Zeldin

New York University Press. 269 pp.

Anti-Zionist Jewish scholars are on a roll. The recent publication of The Threshold of Dissent: A History of American Jewish Critics of Zionism by Babson College history professor Marjorie Feld follows quickly on Emory University professor Geoffrey Levin’s more narrowly focused Our Palestine Question: Israel and American Jewish Dissent, 1948-1978 (Yale University Press, 2023).

Meanwhile, Unsettled: American Jews and the Movement for Justice in Palestine by University of San Francisco Assistant Professor Oren Kroll-Zeldin picks up the tough tone of Dartmouth Professor of Jewish Studies Shaul Magid’s The Necessity of Exile (Ayin Press, 2023). That book asserted that the “Zionist narrative”—not to mention Israeli policy generally—“cultivates an exclusivity and proprietary ethos that too easily slides into ethnonational chauvinism.”

With friends like these, Zionism hardly needs outsiders to tear it apart. But these scholars, like Israeli New Historians such as Benny Morris and Ilan Pappe of a few decades ago, represent a cadre of like-minded colleagues who appear to be creating an academic movement. Members of the group hang together. Magid blurbs Feld’s book as “excellent” and “much needed,” while Kroll-Zeldin blurbs Feld’s book as “fascinating” and “brilliantly” argued, then thanks Feld in his acknowledgments for helping to “shape this book.” Feld offers special appreciation to Levin for “talking over ideas.” Levin thanks Feld and Magid.

Yet even if these scholars amount to what critic Harold Rosenberg famously dubbed a “herd of independent minds,” both supporters and critics of Israel—in fact, everyone troubled by the exploding generational polarization of American Jews and other Americans over the Israel-Hamas war—should read and absorb the two latest entries in the “anti-Zionist” genre. They powerfully demonstrate useful truths about the clash between Zionists and anti-Zionists.

Both books provide strong reportage, adding to one’s literacy about Zionism’s reception in the United States. Feld indefatigably quotes, describes and contextualizes the leading American anti-Zionist critics over some 125 years. Her findings include the undisputed ways mainstream American pro-Zionist Jewish organizations, as well as Israeli diplomats, sought to muzzle anti-Zionist critiques.

Shouldn’t scholarly books arguing for anti-Zionism address pro-Zionist counterarguments?

Kroll-Zeldin, who proudly declares that he’s an “embattled participant” in anti-Zionist activism himself, in turn interviews an array of young people he awkwardly describes as “Jewish American Palestine solidarity activists.” They explain, often at great length, how they got involved in anti-Zionist and anti-Israel organizations.

Feld the researcher nicely brings back to life the voices of America’s leading anti-Zionists and proto-anti-Zionists, starting way back with the Reform leaders who issued the Pittsburgh Platform of 1885 that rejected the goal of a Jewish state. She offers rich portraits of Rabbi Elmer Berger, cofounder of the anti-Zionist American Council for Judaism (ACJ); two of the ACJ’s other key figures, Rabbi Morris Lazaron and Lessing Rosenwald; Henry Hurwitz and his Menorah Journal; and the sardonic journalist William Zukerman (1885-1961), whose trenchant critiques of Zionism still reward close reading.

Feld equally provides full portraits of anti-Zionist organizations and publications: the ACJ, the Free Jewish Club, Breira, the Jewish Newsletter and Jewish Voice for Peace. Along the way she does a fine job of recounting the concerns of classical anti-Zionism, from the fear that a Jewish state would raise questions of dual loyalty in the diaspora to belief that “Zionism would drain money and leadership talent away from thriving Jewish communities outside of the future Jewish state.”

Kroll-Zeldin, for his part, takes us inside such organizations as Jewish Voice for Peace, the millennial- and Gen-Z-fueled IfNotNow, the Center for Jewish Nonviolence, All That’s Left: Anti-Occupation Collective, and Judaism On Our Own Terms, delineating subtle distinctions among them. He describes his own 180-degree switch from Los Angeles-raised Reform Jew and “unquestioning” Zionist to Palestinian solidarity activist.

Kroll-Zeldin the reporter nicely details the rebellions in recent years of some young Palestine solidarity activists against Birthright tours and offers what’s likely the most sympathetic account you’ll find in print of the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement. His aim? To convince self-styled “progressives” on every other issue that they can’t be “progressive except for Palestine.”

They need to begin “unlearning Zionism” and its “myths,” he argues, to train themselves in the best tactics for “liberating Judaism from Zionism.” If you’re still a Zionist, it’s enormously eye-opening to take in how a passionate anti-Zionist thinks.

But there are two more reasons to read these books beyond their solid reportage. First, contrary to what Feld and Kroll-Zeldin believe they’re demonstrating, their books show and document (as did Levin’s) that anti-Zionist criticism, even as major Jewish organizations opposed it, has been alive and well and accessible in the United States since Zionism’s beginnings.

Second, these books, truth be told, amount to a gift to Zionists—because they almost completely lack any critical analysis of Zionist arguments for Israel. Rather, and particularly in the case of Kroll-Zeldin, they’re rife with a drink-the-KoolAid simplicity whenever they shift from reportage to sharing their ideological commitments.

Neither Feld nor Kroll-Zeldin contends, even at the length of a full paragraph, with Zionist arguments. They barely describe them. Both simply assume from the outset that Jewish “social justice” values contradict Zionism and Israeli policy. In their views, anti-Zionists and “progressives” (so-called) are always on the side of “justice”—a concept never remotely unpacked by either—as well as of equality, freedom and the angels.

Zionists, in contrast, line up with the wrongheaded and, sometimes, the devil. To Feld, Zionist arguments are simply “Zionist propagandizing,” a phrase she repeats more than once. By my count, she describes Zionism in America as a “forced consensus” or “imposed consensus” or “manufactured consensus” or “painstakingly enforced” consensus 28 times. But she provides no evidence that support for Zionism was either “forced,” “imposed” or “manufactured.” Rather, by her own account, after anti-Zionists made their points and launched their organizations, the great majority of major Jewish organizations rejected and opposed those points, and so did the great majority of Jewish Americans. Most American Jews simply opposed the anti-Zionist critique.

Similarly, for Kroll-Zeldin, Zionist arguments are just smokescreens propagated by the “American Jewish Establishment” to hide Israel’s “racist violence,” its “occupation and apartheid,” its “human rights abuses” and its “morally reprehensible” behavior, particularly given the “increasingly fascist nature of Israel’s rightwing government.”

The irony of both books is that they replicate the intellectual sins they ascribe to Zionists—one-sided descriptions of Israeli actions, lack of self-criticism, closed-mindedness and suffocating certainty.

Shouldn’t scholarly books arguing for anti-Zionism address pro-Zionist counterarguments? Let me count the ways Zionists might differ.

In the early 20th century, many Arabs from other countries themselves immigrated to Palestine to take advantage of economic opportunities, wealth and jobs created by the Zionists. But when Arabs, in the face of growing Jewish immigration, initiated violence as the tool for resisting Jewish aspirations, Zionist leaders concluded that only a Jewish state, with a Jewish majority, could protect the Jews of Palestine—and later incoming refugees from the Holocaust—from Arab violence.

Soon Zionist militias such as the Irgun and Lehi turned to violence as well, against the British and Arabs. Once the Jewish-Arab civil war began in 1947, followed by the 1948 war of five Arab nations against Israel after Arabs resisted the UN’s two-state partition, the cycle of violence was off and running. So was a practical truth of world geography—you start an aggressive war and are defeated, you lose territory as a matter of justice.

What’s the anti-Zionist rejoinder?

Neither Feld nor Kroll-Zeldin ever mentions Arab violence against Jews. Nothing about Arab massacres of Jews, Arab terrorism or the intifadas as justifications more recently for the Separation Wall, for checkpoints and for the hardening of Israeli sentiment against Arabs. Add October 7, hostage-taking and murder of Jews in the West Bank to the equation. Shouldn’t anti-Zionist scholars address the common-sense argument one hears from Israelis who increasingly express limited sympathy toward Gazans since October 7? In short, “They started it.”

There’s more that anti-Zionists might take on. More objective scholarship has established that Arab intransigence from the 1930s on toward any solution short of full Arab sovereignty over all of Mandatory Palestine, “from the river to the sea,” has foiled multiple attempts to solve the conflict. So does the claim that a right of return for those Arabs “dispossessed” of their homes in 1948 and 1967—usually estimated at 750,000—now includes 7 million Arabs, a unique designation supported by the UN. What’s the anti-Zionist rejoinder?

Many anti-Zionists, to be sure, have replies to these points. Israeli Jews, like Palestinian Arabs, have at times been guilty of brutal behavior and massacres. But it serves no one, and certainly not readers, to avoid the back and forth in one’s book. Yes, one side’s “ethnic cleansing” is another’s “exchange of populations” (once a widely accepted geopolitical strategy for ending inter-ethnic violence, as in early 20th-century Turkey and in mid-20th-century India). Yes, one side’s “settler colonialism” is another’s “return from exile.” Scholars must take on such challenges.

Also open to question is the axiomatic assumption by both Feld and Kroll-Zeldin that progressive values of justice and of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) behoove young Jews to become anti-Zionist. Zionists might ask a simple question in return. How does the existence of one Jewish state in a world with 22 nations under Arab sovereignty (members of the Arab League) and 57 Muslim states (members of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation) not count as a step toward diversity, equity, inclusion and justice? Especially after the expulsion of an estimated 850,000 Jews from their homes in Arab and Muslim countries, many taken in by Israel? What’s the anti-Zionist rejoinder?

Finally, a last two homework assignments for anti-Zionists. “Progressives” usually support migrants and the right of people to leave their homelands and move to a better place, even if illegally.

Why, then, was early 20th-century immigration by Jews to Palestine so evil, especially since many Arabs also immigrated, and some segments of Arab society welcomed it and sold land to Jews?

Anti-Zionist scholars, on the evidence of these books, simply ignore counterarguments to their assumed positions. Although they’re not as benighted as pro-Palestinian college protesters who can’t name the river or the sea they’re chanting about, they share the hypocrisy of attacking Zionism as imperialism and colonialism from their safe spots in the United States. That United States is, after all, a country founded and developed through genocide by Europeans who, unlike Zionists emigrating to Israel, had no previous multi-millennial attachment to the land. Anti-Zionists might come off a little more sympathetically if they began their books with those dedications now so common before book talks on college campuses: “I acknowledge that this book was written on Lenape land, stolen from its rightful proprietors…”

It’s bad enough when students and hyped-up protesters can’t see a wisp of the rationales behind actions they protest. But when PhDs in Jewish studies and Middle East history, privileged to hold professorial positions, can’t do so either, and when their bibliographies cite only scholars who agree with them, we’ve reached a particular low point of academic mediocrity. If The Threshold of Dissent and Unsettled represent the quality of today’s anti-Zionist scholarship, Zionism should survive just fine.

Carlin Romano, Moment’s Critic-at-Large, teaches philosophy and media theory at the University of Pennsylvania.

Moment Magazine participates in the Amazon Associates program and earns money from qualifying purchases.

In the early 20th century, many Arabs from other countries themselves immigrated to Palestine to take advantage of economic opportunities, wealth and jobs created by the Zionists.”

Of course, but the nonjewish communities mentioned in the Balfour Declaration ( for example) were the majority of Palestine with other without Jews.

Feld’s book focuses a lot of attention on the non- or anti-Zionism in Reform Judaism’s 1885 Pittsburgh Platform, which pined for assimilation. She notes that by 1947, mainstream Judaism, including Reform Judaism reversed and rejected those tenets. Something must have happened in those intervening 62 years. But what? What could possibly have happened??