Interviews by Amy E. Schwartz

DEBATERS

Charles Asher Small is the founding director of the Institute for the Study of Global Antisemitism and Policy.

Harvey Silverglate is a lawyer and cofounder of the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression.

INTERVIEW WITH CHARLES ASHER SMALL

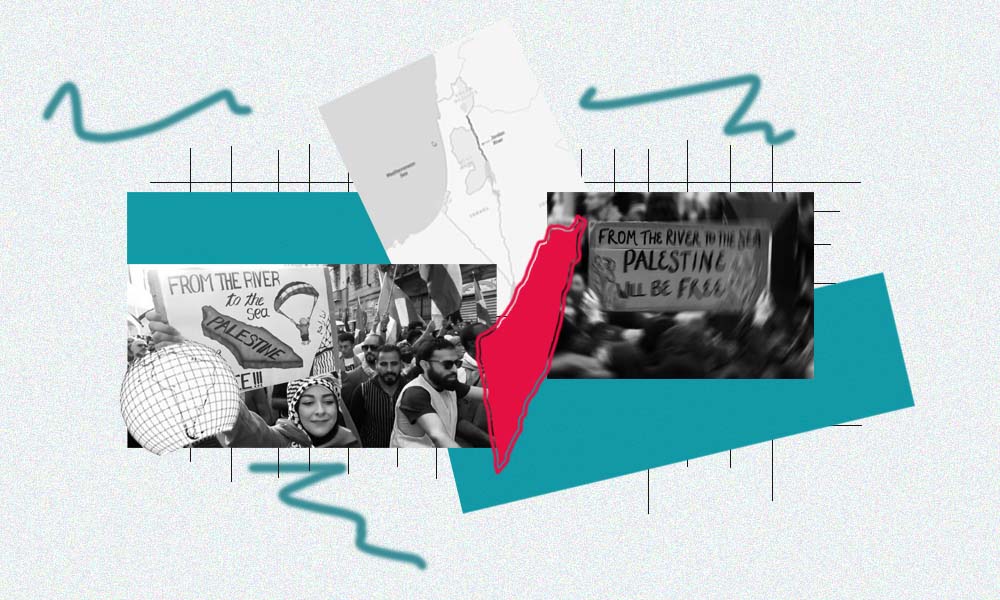

Should Students Be Disciplined for Chanting “From the River to the Sea”? | Yes

Should students be disciplined for chanting “From the river to the sea”?

Yes. Absolutely. I understand the importance of the First Amendment and academic freedom, but even with those rights, there are limitations. You cannot yell fire in a crowded theater. In the current environment, radical leftists and political Islamists are intent on killing Jews and dismantling the State of Israel through violent means. There are intellectuals supporting the genocidal program of Hamas and the Muslim Brotherhood at our best institutions.

At a teach-in at the School of Social Work at Columbia a few weeks ago, I heard very intelligent PhD students citing Edward Said and postcolonial studies, saying resistance to occupation is justified by any means—they literally justified the pogrom that took place on October 7. It’s repugnant to blame the victim of any form of hate and violence. One poll found 70 percent of Jewish students in the United States have experienced antisemitism in the last two months. It’s incumbent on everyone at universities to put an end to this.

Does this specific chant call for genocide?

The Jewish community and political commentators have articulated clearly that it does. Many European countries have sought to ban demonstrations using this chant, including France and Germany. Under the UN’s Convention for the Prevention and Punishment of Genocide, Article 4, incitement to genocide is a crime, but under some interpretations of U.S. law, the speech only becomes incitement in retrospect if the genocide was carried out. But any call for genocide that’s backed up by threats, violence and intimidation needs to be stopped, particularly at a university, where young people learn to be citizens.

What kind of official response, if any, is appropriate?

Universities should ban intimidation of any student, especially based on any form of hate and racism. There should be federal and internal investigations into the impact of universities’ receiving billions of dollars from Qatar, whose government supports the goals of Hamas. Anyone who is overtly racist, sexist or antisemitic, and articulates it in a way that excludes any member of the community from functioning as a full and equal member, needs to be disciplined. The leaders of groups like Students for Justice in Palestine, who define themselves as not just supporting the struggle but part of the struggle, should be expelled. Those who are maybe more naive but still engaged in organized antisemitism should be put on probation and given more education. Universities need to adopt the IHRA definition of antisemitism and implement it effectively.

Universities should ban intimidation of any student.

When do rallies and protests rise to the level of a Title VI violation? I’m not a lawyer, but I met many students at New York University and Columbia who received death threats to their faces, young women whose fellow students went up to them saying they would be murdered and raped like the people in southern Israel. I knew this stuff intellectually, but hearing from a young woman who stays in her dorm knowing she’ll fail her classes, because her fellow students are calling her a child-killer—it was stomach-turning. A brilliant student I mentored at Oxford, an Israeli-American Jewish woman, left Oxford because she didn’t feel safe. So there’s a real toll to this intimidation.

Does it matter if students know which river and which sea? When somebody commits a crime naively or out of ignorance, they still commit the crime, but the punishment should be lenient. If it’s premeditated and conscious, punishment should be more significant. We’re all responsible for our actions and nonactions.

How can universities encourage civility on campus?

Emmanuel Levinas, the great Jewish philosopher, said two powerful things that inform my work. First, he said that in Jewish ethics, the moment we see our own face in the face of the Other is the moment we become human. He also taught that if any ideology dehumanizes and objectifies a group of people, you can’t tolerate that ideology or negotiate with it. To protect the space for learning, faculty and administrators need to engage in serious study and conversation about the state of antisemitism and antidemocratic ideologies in the university. If they’re willing to have more classes, programs and research on contemporary antisemitism, not to blame Israel or Jews for the problem but to understand the depth of it, that would be something positive.

What would a healthy public square look like? What would students be chanting?

Where all parties are on a quest to strengthen democratic principles and notions of citizenship, dignity, respect and equality, let them chant loudly and argue with vigor. But if anyone is arguing for racism, demonization, antidemocratic values or the elimination of any group, that crosses a clear line.

INTERVIEW WITH HARVEY SILVERGLATE

Should Students Be Disciplined for Chanting “From the River to the Sea”? | No

Should students be disciplined for chanting “From the river to the sea”?

No. Two words: Academic freedom. The U.S. Supreme Court in both its liberal and conservative iterations has agreed on very few things, but they’ve agreed on free speech issues. The parameters of free speech are extraordinarily broad and have been consistent for decades: In the wider society, speech, no matter how offensive, is allowed, except for a few narrow categories: libel, slander, defamation, threats. Most people think you can’t yell fire in a crowded theater, but that’s wrong; you can’t falsely yell fire in a crowded theater. Of course you can yell it if there’s a fire. In the written arena, you can be sued for copyright violation, and if you’re a university president, as we’ve learned, you can be dismissed for plagiarism. So speech protections are very broad, and the things Palestinian students and their supporters have been saying on campus, tough and unpleasing to a lot of people including myself, are 100 percent protected and should be allowed.

I’ve been in hostile environments. I went to Princeton in 1964, and it was a hostile environment for a Jewish kid. Someone asked me how I could stand the antisemitic taunts. I decided then that I prefer loud antisemites to quiet antisemites. I find it very useful to know who hates me. It’s more important to protect hate speech than love speech. And the most important arenas for free speech are the academy and the press.

Does this specific chant call for genocide?

You’re allowed to call for genocide. You just can’t take steps to actually commit it. I personally want to know who’s calling for genocide of Jews. If they’re not allowed to say it, I won’t know. People think the First Amendment is theoretical, but it’s actually a practical tool for surviving in a free society.

You can encourage civility, but you can’t enforce it.

What kind of official response, if any, is appropriate? The job of the university is to provide a forum where all kinds of points of view can be expressed safely. I don’t think they should make pronouncements from on high with regard to public issues. Claudine Gay could have saved herself a lot of aggravation if that had been her policy.

When do rallies and protests rise to the level of a Title VI violation?

When they stop people from entering a building, when they’re so loud they stop people from hearing or studying. A rally is not allowed to be disruptive of the educational enterprise. The Supreme Court has settled that, just as it has settled the parameters for rallies in the street. There are close cases. The protest at Harvard’s Widener Library, where students did not speak but took every seat in the main reading room and quietly hung banners with Free Palestine slogans, was disruptive to people who wanted to study there, but it’s hard to prove that as a factual matter. There are ways—you could set time limits on using a seat without studying, and enforce that with monitors—but you need leadership that can think its way out of a paper bag.

Does it matter whether students know which river and which sea?

If you required that every demonstrator know what he or she is talking about, you’d have to do intelligence tests on some of the stupidest people in the world. We don’t educate our children very well, so we produce a lot of people who are unsophisticated about what the world is like. If you’re familiar with world history, you’re very careful before you call for genocide. It’s Santayana: Those who forget history are condemned to repeat it. It would be better if students could argue these issues out, but we’ve created an atmosphere in academia that is not friendly to the true expression of one’s beliefs because university officials may claim that something you say constitutes hate speech. Well, it doesn’t. There’s no such thing as hate speech. There’s hateful language, but it’s 100 percent protected. College administrators with nothing else to do have invented rules and kangaroo courts and this idea of enforced civility, which is impossible. You can encourage civility, but you can’t enforce it.

How can universities encourage civility on campus?

They can sponsor programs where civil libertarians come in and speak about the parameters of protected speech, and they can teach that civility, though optional, is an important adjunct of education, because we have to listen to and learn from one another. If you want to be an educated person, you should voluntarily undertake to listen to people who don’t agree with you. If you haven’t changed your mind about something in four years, you’ve wasted your money. It’s particularly important here, in the most diverse country in the world.

What would a healthy public square look like? What would students be chanting?

Whatever they believe.

I agree with Harvey Silvergate.

We are seeing all kinds of hand-wringing about First Amendment speech on college campuses. For all practical purposes, colleges and universities acknowledge that the First Amendment applies to private institutions, even though private institutions might challenge that concept (citing one of my cases, Rendell-Baker v. Kohn, 457 U.S. 830 (1982)). Accepting the principle that the First Amendment applies, the First Amendment cases provide the guidelines for the exercise of free speech on campuses. Aside from defamation and other well-known exceptions (e.g. shouting fire in a crowded theater that is false), three cases should provide guidance: Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire (1942), Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969) and Snyder v. Phelps (2011), all of which establish the proposition that speech that incites imminent danger can be prohibited. The question in each instance is what constitutes “imminent” danger. I think the task of colleges and universities should be to develop guidelines that implement the First Amendment protections, not limit them.

And, arguments that colleges and universities should keep silent about the issues of the day fall flat with me; it is overreaching and they are “people” too (Citizens United). But if they are to exercise their First Amendment rights, they have to take special care that those who disagree with their views can state their own, safely, and without retribution for disagreement. Whatever happened to “teach-ins” that were used to debate the Vietnam War when I was a student?

For me, the application of these rules should be straightforward. Colleges and universities should permit speakers of all views to speak and students and others have a right to listen to those views, or not, but they do not have a right to shout down the speaker. I remember that, as a college student, the American Nazi, George Lincoln Rockwell, came to the Ohio University campus. I was one of a group handing out leaflets to urge people not to attend, for his views were well-known and abhorrent. I chose not to attend; others decided otherwise, which was their right. He spoke and the university is still there and continues to be a “marketplace of ideas.”

P. S. to my comments above. For anyone wanting to know how the content of speech was in the early and developing years of our Republic, I invite you to read the late New York Times columnist, Anthony Lewis’s book, Freedom for the Thoughts That we Hate. The title of the book is taken from a dissent by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes in United States v. Schwimmer, 279 U.S. 644 (1929). I used this book in teaching constitutional law and reading this book will help people understand the issues of today more clearly.

We should stop treating the U.S. Constitution as if it is the greatest guide in the world to a free and democratic society. There are many things wrong with the Constitution (recognition of slavery. lifetime appointment for SCOTUS, etc.) and the Bill of Rights (see the confused and irrational 2nd Amendment). There are other democratic countries where hate speech is restricted. The First Amendment and Academic Freedom have become a slogan, while arbitrary decisions are made on other grounds about what is tolerated and what is not, while proclaiming allegiance to these principles. All public speech that express, propose or incite hatred or violence on the basis of identity should be restricted. That doesn’t mean people cannot utter their thoughts in private, or confess their prejudices in a forum. It doesn’t mean certain members of a self-identified group cannot be called out for an offense. It means that people are restricted from using public forums, whether a campus, a newspaper or an Internet site, from promoting the idea that a certain group of people should be detested based on their identity. Allowing hate speech in public can make large numbers of people more susceptible to bigoted ideas, including participating in or condoning violence or repression. It therefore represents a tangible danger to the identified persons.

BTW I taught on college campuses for 16 years. I believe in academic freedom. It does not need to include the right to characterize Muslims as “terrorists”, Israeli Jews as “settlers”, or other ethnic slurs, in order to keep the campus a lively place where many ideas contend. There is no value in allowing ideas that contradict the most basic humanitarian values to enter into that environment; they are not what academic freedom is intended to protect.

Since last October 7, many people have miscast the nature of debates as involving free speech. Intimidation is not protected speech. Within a university setting, actions that impede students’ right to study effectively do not deserve protection. Intentional, propagandistic lying has no place within a university. To paraphrase what a Supreme Court Justice said decades ago: the First Amendment is not a suicide pact.

I agree with my law school classmate Harvey Silvergate and admire his longstanding vigorous advocacy for academic freedom. But while I disagree with Messrs Small and Alterman, I understand where they are coming from. In my senior year of high school (1959-60), shortly after I made my first donation to the ACLU, I signed a petition to have the City of New York ban a Nazi demonstration in Central Park.