This story is the third-place winner of the 2019 Moment Magazine-Karma Foundation Short Fiction Contest. Founded in 2000, the contest was created to recognize authors of Jewish short fiction. The 2019 stories were judged by American actor and author Max Brooks. Moment Magazine and the Karma Foundation are grateful to Brooks and to all of the writers who took the time to submit their stories. Visit momentmag.com/fiction to learn how to submit a story to the contest.

His children relocated him from the small Greenwich Village apartment where he and his late wife, Susan, had raised their family, to the Scarsdale Sinai Home, for a short time on the assisted living unit and then to the Alzheimer’s floor. There things would have ended, the rabbi scholar receding into the background until the magnetic pull of his condition attracted some illness. He would then slip away like a well-circulated library book, all but forgotten, buried deep in the stacks, tattered and obsolete. That would have been the end, save for what happened on a Sunday morning. On one of his visits, Mankewitz’s son, Aaron, saw a flyer in the lobby welcoming residents to use the Jewish Community Center’s swimming pool.

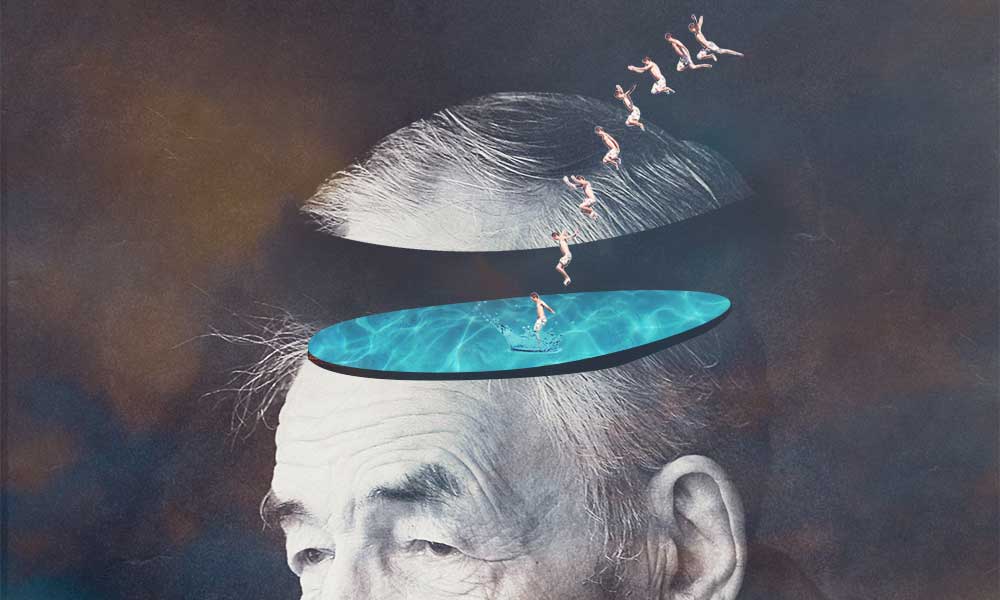

His father had been a swimmer. Daily for an hour he’d swim, dreamily pacing up and back. Sometimes the slow lane would be his alone. Sometimes he’d share it with others in a 25-meter oblong, everyone wrapped in their own watery worlds. This routine benefited his blood sugar. His stomach, which at the beginning hung over his skimpy Speedo like a Dali watch, receded beneath his suit. This regimen concentrated his mind. He’d emerge from his exertions filled with sharpened ideas about Buber, Kant or Flagler, or any other textual issue that occupied his mind that morning.

Mankewitz would declare to the world that his new discipline had brought with it renewed strength, health and a great lucidity of mind. “Swimming made me a smarter, stronger, a healthier Jew. Call me Gefilte,” he’d say, though only one person ever did.

The dementia that attacked Rabbi Doctor Mankewitz’s brain as he neared 60 took its time making its final, debilitating mark. Yet the man who for the better part of three decades had taught Jewish thought at the Seminary for the Study of Judaism finally succumbed. At 63 he retired.

So late one Sunday morning Aaron bundled up his father against the February cold and drove him to the JCC to splash around the wading area. He helped his father struggle back into his old Speedo, remarkably still serviceable if slightly tattered, and guided him to the pool. They descended slowly into the warm water of the wading area. Aaron figured he’d help his father through some water exercises, and after 15 or 20 minutes, they’d call it a day and return to Sinai.

But that’s not what happened. Once waist deep, Mankewitz stood up straight and tall, his hands hugging his sides. Looking left, then right, he slogged over to the swimming lanes and ducked beneath the rope. He put his head into the water, kicked off the side and headed down, swimming as in the old days, one lazy stroke after another, legs kicking, head moving, arms rotating. At the other side, he turned around. Again, he kicked hard off the side and swam back to his astonished son and stood, water dripping into his eyes. He looked up at his son and said, “God damn, Aaron, that was great. I’m going again.”

And so he did, back and forth, for five laps. Then he stood once more, breathing hard, eyes red from the chlorine. He looked up at Aaron, who was standing by the pool’s edge.

“My God, man, I feel great. Let’s get a coffee.”

They made their way to the locker room, Mankewitz bouncing with energy. He changed without his son’s assistance. On their way out, he slapped his son on his back and said, “Yes, a skim cappuccino and a bagel with a shmear.”

“Yes, Dad, for sure.”

They made their way to the JCC’s Starbucks, Mankewitz striding vigorously, the son following. When Aaron caught up, he directed his father to one of the tables while he went through the line. He returned with the coffee and bagel, overflowing with questions. But Mankewitz sat staring blankly, his chin resting on his chest. The momentary eruption of clarity had vanished, Mankewitz used up, an old birthday balloon, the helium escaping into the sky.

Aaron and his sister Shira determined to see what would happen during another visit to the pool. Again, Mankewitz took to the water like a young gefilte swimming upstream at springtime, managing this time a 15-minute run, eight laps. He climbed out of the pool, again restored, again demanding coffee and a bagel.

“Sure, Dad,” Aaron said, putting his arm around his father as they hastened to the locker room, Mankewitz speaking about the weather, about philosophy, filled with curiosity about current events. With his pants on, he raised his bathing suit with two hands. “Still fits, eh?” They rushed to the Starbucks where he sat, the sun streaming upon him from the skylight while Aaron bought the food and beverage.

Mankewitz savored the coffee in the white and green cardboard paper cup.

Eyes meeting, the two nodded at each other in silence.

Mankewitz took a bite of his bagel and was transported back to that small Jerusalem bakery where he and Susan would buy challah on Friday afternoons while there on sabbatical. “A shame your mother isn’t here. I would so love a talk with her,” he said, looking at his son, whose eyes were filled with wonder and tears. Mankewitz added, “And you. How are you?”

Aaron wanted to blurt everything at once, about his two young kids, about Shira, about the world, above all about the phenomenon of his father sitting before him resurrected by water like an Old Testament miracle. But the words caught in his throat. For a long moment he couldn’t address the animated person sitting before him. When he did open his mouth to speak, Mankewitz rested his half-finished cup of coffee on the table, and began rocking his head up and down, eyes half-shut, on his way back to the mists.

“Okay, Dad,” Aaron said. “Let’s finish up and I’ll take you back to Sinai.”

Mankewitz gnawed on the bagel and finished the coffee, neither now of particular interest. The two shuffled to the car. Aaron accompanied him to his room, where he took off his father’s shoes and helped him lie down. He kissed his father on his cheek and went home.

Aaron and Shira learned that Mankewitz would return to his old self roughly equal to the amount of time he swam. As the length of time he could swim increased, so, too, did the time he remained Professor Mankewitz, minute for minute, for a maximum of about an hour, no more than three times weekly. For three hours a week, he became the old rabbi doctor, a ferocious conversationalist and intellectual.

Tests showed no change in brain function. Beyond that one test, the family resolved to decline any further testing. Nobody understood this plunge back into reality, yes, but no one was going to understand it, either, if it meant a continuing battery of medical tests that would interrupt these precious moments.

“Tell them to just leave me the hell alone,” he said to Shira, during one of those afternoons at Starbucks. “I’ve not returned from the depths of Sheol to waste my time becoming a medical marvel. Let it remain a mystery.”

When the news got out that Mankewitz became compos mentis after a swim, visitors would join him for coffee—so many they needed to make an appointment. He literally held court, king for an hour.

“It’s the damnedest thing,” he said to Lieberman, the dean of the seminary. “I emerge from a thick fog and into the sunlight, like I’m a mystic encountering enlightenment. Only I’m not in a warm room on some prayer rug in the lotus position, or in a leather chair humming a melody. I’m in a pool halfway down the lane stroking and kicking.”

“Sholom,” said his old friend. “That moment you come back to life, what does it feel like?”

“What’s it like to be sentient in the middle of the bloody pool? Great,“ he said, but then grimaced. “Not immediately. At first it’s terrifying. I’m in the water stroking, dumb as a stone. Then consciousness smacks me head to toe. I have no idea how I got there. Then I remember. I swallow some water, fight off a moment of panic. I calm down and swim for about an hour. Then I come and drink coffee and talk with whoever’s sitting opposite me until I recede into the vapors.”

“What do you remember?” Lieberman asked.

“I see crystal clear my last day at the Seminary saying goodbye. Mankewitz the cabbage head shambling off to the home. All of those sympathetic eyes, maybe a drop of Schadenfreude in one or two.” He sipped his coffee. “Then everything. I remember everything. A strange existence, I can tell you.”

Lieberman nodded at this obvious truth. “And when the hour ends?”

“That’s not gradual. It’s like in the pool, a moment of dis-enlightenment dropping on me like an old blanket. I’m sitting here talking, and it’s gone. Next thing I’m back in the pool, choking on a mouth full of chlorinated water. In between I live in a fog, people moving in and out like ghosts. Occasionally something gets me. Food usually.” He paused and inhaled the aroma of freshly ground coffee beans. “Meatloaf. Believe it or not, meatloaf. Every Tuesday. For five minutes I’m conscious, a slice of meatloaf in front of me,” he said. Then the light left his eyes.

One morning Shira sat at the table, her deep, raven eyes staring at her resurrected father, a jumble of emotions pouring from them.

“So? What’s new?” Mankewitz said.

“Not much. We finalized the divorce last week. I got the house. Henry got the dog. We split the boy.”

“Not down the middle, I hope,” he said, lifting the cardboard cup. “Henry always seemed more attached to the mutt than you.”

“I don’t miss walking her in the winter in the middle of the night. Let Henry go out at midnight when it’s 20 degrees,” she said, looking up at the swirl of gray clouds through the skylight. “I do miss waking up in the morning with the thing in bed. The dog I mean.” She reached into her purse and removed the photograph of a teenage boy, hair akimbo, earring in one ear, dressed in a soccer uniform, smiling like he owned the day. “Teddy’s a senior now. His college applications are out.”

“A senior?” Mankewitz said. “God damn. This disease runs all hell over my sense of time. I barely remember a kid just past his bar mitzvah.”

“You’re sick a while, Dad. When we come to see you, you’re always in another dimension. The last time we found you wandering the halls looking for a repairman for your refrigerator,” she said.

“I always did like keeping my kitchen appliances in good working order.” He sipped some more coffee. “A senior in high school,” he mused. “How’s he doing?”

“The divorce was difficult. Your illness bothers him. He has a hard time visiting your body when your mind’s elsewhere.”

“Where’s he want to go to college?”

“He’d like to go to Yale, but it’ll be a stretch. His grades and scores are on the cusp. His extracurricular work may pull him over. He’s got a couple of applications to some other schools. He likes Emory. Brandeis, too.”

“Nothing wrong with Emory. And Brandeis, of course, there I have a couple of connections. I hope he used my name.”

Shira nodded. “He’s also got an application out to Stony Brook and a couple of other places. He’ll get in somewhere. But a parent worries.”

“We worried about you and Aaron.” He took the photograph and looked closely. “Handsome boy.” He leaned, considering the picture. “He’ll do fine,” Mankewitz said. “Does he have any idea what he wants to study?”

“He’s strong in STEM, but he also loves literature and writing about it.”

“I remember his bar mitzvah speech like it was yesterday.” Mankewitz snorted. “For me it was yesterday.”

Shira smiled, but her tear ducts were filling.

“An excellent speech,” he said. “He wrote about the Flood like a graduate student, a deep analysis of the language and the themes, not very good as a speech, actually. Too complicated for a crowd ignorant of the challenges of the story. He understood something deep about Noah and the Ark, what Noah must have felt like, surviving the destruction of the world. Never thought a boy could get the pain of the story. ”

“You helped him,” his daughter said.

“Sure, I asked him a couple of hard questions, corrected some grammar. But the work was his. He had brains and he had empathy. At the end of the service, he thanked me. Called me Grandpa Gefilte. Man, I loved that.” Mankewitz smiled. “He could do worse than studying literature. Reading great books changes a fellow. It’s true, literature majors often wind up managing a McDonald’s if they don’t have a plan, ” he said. “Yeah, forget it. Make him do science and think seriously about becoming a doctor. Like you. Books he can read on the side.”

“Your grandson the doctor,” she said. “Maybe. He’s got time.”

“Send him by. I’d love to see him.”

“I’ll send him next week.”

“It’ll seem like a couple of hours to me. Five minutes. The meatloaf minutes.” Mankewitz took a bite of his bagel and nodded off, dreaming, perhaps, of a parade of broken kitchen appliances. The next time, Teddy was his guest. Now over six feet, he towered over his grandfather. He had his mother’s raven eyes. The boy shifted from one leg to another. Mankewitz beamed. “I’m elated you came, Teddy.” He gestured toward the chair. “Sit down.” Teddy sat but did not speak.

Mankewitz saw something in the boy’s face.

“What’s up, kid?” he asked. “Spill.”

Teddy bit his lower lip and said, “Every time I visit you at the home, you keep calling me Bernard. Never Max or Louie. Always Bernard.” “You know there’s something wrong in my brain,” he said. “Sometimes I say the darnedest things.” “I get that your brain doesn’t work right. But calling me Bernard all the time, it bugs me.” “Why?” “You seem so certain when you say it, like you’re really talking to someone named Bernard, not someone random, and not me.” “I’m not calling you Bernard now, am I, Teddy?” “Obviously not. Now you’re, like, normal.”

“I’m a defective light bulb, blinking off then on, mostly off. Now I’m okay, but any minute I’ll switch off and become my lesser self.”

The air filled with the noise of baristas steaming milk for expensive coffee drinks.

“Who is Bernard?” asked Teddy. Mankewitz’s time holding court should not have included dredging up the past. He sighed. “Bernard and I studied at Brandeis together. Smartest person I ever knew.” He looked down at the table. “He wasn’t the happiest person I ever knew. Or the best dressed. I think he owned two pairs of jeans, maybe four sweaters, a couple of tee shirts.” Mankewitz thought back to the building on the top of Brandeis’s campus where most of his department’s classes met.

“Bernard understood the interior of a text. Any text. He could drill into the author’s mind. Then he could tie that text to all the texts that had any kind of relationship to it, going back centuries and forward to the present. He had a brilliant future.” Mankewitz sighed. A tear streamed down his face. It nearly broke Teddy’s heart.

“What happened?”

“For as long as I knew him he suffered from depression. The year we sat for our orals, his depression worsened. Not everyone knew. Most people saw only a great intensity. He could sublimate it in class, focus on the discussion, which he usually dominated.”

“I have people like that in my classes. I hate them,” Teddy said.

“When you’re older, you’ll find the strength to admire those people. There’ll always be someone smarter than you. I overcame my envy of Bernard and I just admired the hell out of him. I loved watching him think.”

“Maybe,” Teddy said.

“That fourth year the depression grew worse. Most of fall semester he stayed in his place studying. Hardly ever left except for class. He owned this old clunky VW Beetle. Green. Barely worked. Sometimes I’d see him chugging up the hill in the middle of campus, and I’d wonder if he’d make it.”

Teddy smiled. He knew that hill from his visit to Brandeis.

“At the end of the semester he took off to New Jersey to visit his folks.

The Mass Pike was icy. Somewhere past Palmer, the car skidded off the road into a ditch. He didn’t have his seat belt on—schmuck never wore his seat belt.” Mankewitz looked aside for a moment and coughed. “I’ve always suspected he turned the wheel and took himself down that ditch. All of that brilliance just rolled over and over.” Teddy reached across the table and grasped his grandfather’s forearm. “What an awful story.” “I lent him 40 bucks for the gas and tolls. Bastard still owes me 40 bucks.” He looked hard at his grandson and again he sighed. “But that was a long time ago. The work he would have done.”

Teddy’s face suggested he understood something deep and melancholy about his grandfather.

“He had eyes like yours,” Mankewitz said.

The now familiar blankness filled his face.

Some months after his resurrection, in the middle of a conversation with an old student, a powerful sensation rose and crashed down on Mankewitz, a wave at high tide.

“The Flagler book,” he whispered.

“What?” his companion asked.

“Flagler. My book. Get it,” he said with rare harshness.

Mankewitz was talking about his unfinished manuscript on the writings of Ludwig Flagler. He’d devoted untold hours, thousands of hours, to this project, his effort to give Flagler the hearing he deserved. Rabbi Ludwig Flagler (1898-1944) had joined a small group of German Jews struggling to renew Judaism in light of the challenges posed by modern thought. He believed the Hebrew Bible to be the product of the ancient Israelite genius for connecting with the Divine Mind. The complexity of the Bible’s language and ideas demonstrated, Flagler argued, a union that provoked the creation of great spiritual literature unlike anything seen before or since.

Secondary sources would mention Flagler as a minor character in the drama of the Jewish intellectual renaissance in Germany. Obscure he remained to Mankewitz until one day he was perusing the closed stacks in the Seminary’s library. He came across Flagler’s magnum opus, Torah and the Israelite Mind. Curious, he pulled the book from the shelf and paged through as he did occasionally with little-known books. Usually, he’d read a page or two in the middle and return it to the shelf, willing to let what had been forgotten return to obscurity.

But Flagler’s book captured his attention. The book’s thesis impressed him, that the ancient Israelites possessed a genius for meeting the Mind of God. Mankewitz had a sabbatical coming. He resolved to have a closer look.

Out of that sabbatical study emerged Mankewitz’s commitment to write the first book-length analysis of Ludwig Flagler’s thought. In three years he’d translated the book. He’d written several articles on Flagler’s theology, linguistics, hermeneutics, on his sources, fully expecting to produce that final book. The Flagler project, however, ceased when dementia robbed Mankewitz of his mind. The Flagler notes resided on a flash drive that lay in a brown envelope in one box among several holding collected Flagler materials along with hard copies of Mankewitz’s articles and what he had written thus far on him. From then on, Mankewitz spent his waking hours on Flagler. Meetings with friends or family nearly ceased. After his swim, he’d come to his table, a MacBook plugged in awaiting his arrival. He’d sip coffee, listen to jazz from Spotify and absorb himself in his notes. Mankewitz continued hoping he’d resurrect Flagler and bring him to the audience he believed was in need of his central idea, that at one time a small group of humans in a desert locale conversed with the Infinite and the Infinite responded.

On one such morning Mankewitz looked up from his computer to see Teddy, Frappucino in hand, face lit up like the eighth day of Hanukkah. Mankewitz’s first impulse was to say, go away, boy, can’t you see I’m working? But this was Teddy. He closed the computer and smiled.

“Hi, Gefilte,” the boy said. By the way his grandson was vibrating he knew something big had happened.

“Get to it, boy.”

“I got into Yale.” He ran his fingers through his hair. “I didn’t think I would, but I got in. Awesome, right?”

Mankewitz grinned at the young man, pride filling his chest.

“Very awesome,” he said. “But no surprise. A great head rests at the tip of your body. You’ve got your mother’s eyes and your father’s height and both their brains. You got brains of your own, too.

Hell, maybe they’re mostly yours.”

Brandeis would have been fine. Nothing wrong with Stony Brook or Emory. But Yale, that was an achievement. Mankewitz went over to his grandson, hugged and kissed him on the cheek.

“Have a seat, man,” he said, pointing to the chair.

Eyeing the mass arrayed before his grandfather, Teddy said, “You’ve got a big pile of stuff here.” He picked up a loose paper and looked it over. “How’s it going?” Mankewitz took the paper and returned it to its pile. “I don’t know,” he said, surveying the material. “I really don’t know. I’ve written pages and pages. Three days a week I sit on my throne, organizing and reorganizing my notes, writing and rewriting an hour at a time.” He let out a hard sigh with such force that a couple of pages rose and glided down the table. “Something’s missing,” he said as he collected the pages. “I’m worried I’ve lost the heart of the project.” He raised the lid of the computer and read what he’d written that day. “I’m afraid I’m not going to make it.”

Ted found a place on the table to rest his drink.

“What do you think the heart of the project is?” he asked.

Mankewitz took a breath and said, “Sometimes things lie behind the actual words. I’m trying to reach that thing behind the words, Flagler’s and mine.”

“I don’t understand.“

“No, of course not. It’s my own mishegos. Let me explain.“

He closed his eyes.

“A lot of writing about God is abstract. Sometimes someone writes about God from a totally disinterested view. He’s analyzing some theologian’s ideas, of course, but he doesn’t believe a word of it. Flagler, Flagler was up to something new and immediate. He thought he’d found a pathway beyond the world that returned to the world.”

“I don’t get it.”

“Okay,” said Mankewitz, slipping into professor mode. “There’s this story. Moses is receiving the Torah on Mount Sinai. The entire Five Books from Genesis to Deuteronomy. The Israelites, you know, were a mess. Three months before they’d been slaves, ignorant through centuries of servitude,” Mankewitz said. “What could they possibly know from a Jewish text?”

Ted grinned at his grandfather. “You never think of these things. You figure the Israelites are the ancient Jews, and Jews are smart, right? But how can you be smart when you’ve been a slave all your life?” Teddy said.

“Moses says to God, ‘Master of the universe, these people they’re a simple lot. Yesterday they were slaves and today you’re asking them to understand what it means when You tell them You created the world. What good is your Torah, if no one can understand it?’”

The room filled with the familiar hissing of milk-steaming machines, grinding beans, the sounds of commerce.

“And what did God say?” asked Ted.

“Well, God says to his prophet, ‘Then let them read between the lines until they can read the lines. And once they can read the lines, let them read between the lines again.’”

Teddy rubbed the back of his head. “Okay, Gefilte, what in the world does that mean?”

Gefilte looked at him and silently counted to ten. “You’re the one going to Yale, boy. You tell me.”

But the discussion that morning ceased. The meter on Mankewitz’s hour had expired. The light faded from his eyes as he rejoined the deep fog.

The next time Mankewitz arrived for his coffee, bagel and bout with Flagler, there stood Ted, Frappuccino in hand.

“I think I know what the story means,” he said with all the excitement possible for a teenager. Placing his coffee on his corner of the table, he sat down. “And,” he added, “I think I can help.”

At the moment he’d re-entered consciousness mid-stroke in the pool Mankewitz recalled that last conversation. He’d hoped Teddy would be there at the table.

“So?” he asked.

“It’s simple, really. That story’s about what’s between the lines the first time and what’s between the lines the second time. The spaces are always the same, but they’re also different.” Mankewitz nodded. He wasn’t surprised. This was the young man who at his bar mitzvah taught something profound about Noah and the Ark, about the unfathomable sadness of the end of the world by water. “Maybe you’re getting it, kid.” Teddy said, “The first time the Israelites put their noses in the Torah, they saw lines of text but couldn’t understand a thing. So when they looked at the spaces in-between, it gave them something that comforted them.” “Right,” said Mankewitz. “Knowing that sufficed. When they could understand the words during their wanderings, the spaces in between allowed them to explain the words.” “What do you mean?” asked Teddy. “I mean that when you dig between the lines, you play out the changing and deepening meaning of the words.”

The chorus of “Born to Be Wild” ascended from Teddy’s shirt pocket. He looked at the screen. “It’s my girlfriend.” “Girlfriend?” Mankewitz said, raising an eyebrow. “Nice. By all means take it.”

Teddy walked a few feet away and returned quickly.

“So what’s her name?”

“Tamara.”

“She’s Jewish?”

“Yes, Gefilte,” he said in an irritated tone. “She’s Jewish. I’m meeting her when we finish.”

“You’ll be out of here in less than an hour. You can set your watch by it.”

“No rush. I am in a hurry to get back to our discussion.”

“Here it is. On Monday the Israelites were slaves. On Tuesday they’re heading out of town, terrified Egyptians throwing jewelry at them like candy. Wednesday they’re across the sea, the Egyptians all good and drowned. A great story. But what’s the meaning of that moment beyond the moment? That meaning shouts out time and again from between the lines of what God said amidst all that smoke and thunder.”

Mankewitz stopped. The old professor hadn’t intended a speech, but an academic rabbi cannot hold back. He must hold forth. Teddy said, “I know what you mean. The meaning of freedom lies between the actual words.” “We always have to rethink what freedom means,” Mankewitz said. “The meaning’s always slightly different, rooted in the moment.”

“Something new rises?”

“Constantly from between the lines.”

“But what’s all this got to do with the heart of your project?”

“What do you think, Yale boy?”

Teddy stroked his chin like he had a beard. “Maybe it’s like this. Flagler had this idea that the Bible comes from the intersection of God and the Israelites.”

“You’ve read my stuff?”

“You gave a lecture at some conference. I found it online.”

“God bless the internet,” Mankewitz said.

“Those texts in the Bible, even they’re sort of between the lines, right? The books are not from God. They’re some version of God.”

“Very good, Teddy. The text’s dynamic. It always will be. It has to be.”

“So if you know that, what did you lose, Gefilte?”

“That dynamic. I’ve lost that sense of how to renew. That’s what Flagler tried to teach us,” Mankewitz said. “I write page after page, but none of it’s right. The cord between Flagler and me has been severed. I can’t reconnect Flagler to the world.” Teddy walked to his grandfather and massaged his shoulders. “Maybe I can help.” The offer startled Mankewitz. Flagler had always been a solitary task. Writing was always a private matter, alone in a room. Like swimming, writing was a private occupation. Maybe Teddy could help. “A capital idea. Let me think about it.” But Mankewitz’s head drooped. The day’s run was over. He returned to the home and Teddy met up with his Jewish girlfriend.

Next time Gefilte awoke in the pool, he recalled his grandson’s proposal. He spent the remainder of his time in the pool contemplating the possibilities. He thought of that old Hebrew chestnut, l’dor va’dor, the passage of tradition to the next generation for them to seize it, adapt it and change it. He’d lost his thread to Flagler’s ideas, but perhaps Teddy could find it and make his own. Give the job of finding what’s hidden between the lines to a 17-year-old kid with an earring and a Jewish girlfriend. What’s there to lose? Mankewitz arrived to the coffee shop pumped up from the swim. Teddy was sitting among the Flagler materials, a large, half-finished frappuccino resting on the table before him, wearing a grin as wide as a river.

“Hi, Gefilte. I’ve come to help. I’m not taking no for an answer.”

“You’re smiling.”

“I came to see you during the week. You called me Teddy.”

“Must have been having a good day,” said Mankewitz. The old professor sipped his coffee and regarded the young man over the rim of the cup. “Let’s begin, then, shall we?” he said.

Phil M. Cohen is an award-winning novelist and short-story writer and an ordained rabbi who holds a Ph.D. in Jewish thought and an MFA in fiction. He is the author of more than 20 published stories and of the eBook Lucky 13. Cohen lives in Greensboro, North Carolina with his wife Betsy and two dogs.