This story is the third-place winner of the 2013 Moment Magazine-Karma Foundation Short Fiction Contest. Founded in 2000, the contest was created to recognize authors of Jewish short fiction. The 2013 stories were judged by writer, editor and professor Alan Cheuse. Moment Magazine and the Karma Foundation are grateful to Cheuse and to all of the writers who took the time to submit their stories. Visit momentmag.com/fiction to learn how to submit a story to the contest.

My mother’s hands are red and chapped, crooked from rheumatism, or “ramates,” as she calls it. She’s been to the baths in Birstonas once or twice and the doctor has advised her that if she can’t go to a spa, she should at least soak once or twice a week at home in salted water, especially in winter. But she hasn’t been doing this since I’ve been home on my visit, complaining that it’s too cold and drafty, besides being too much work for my sister Mera to have to haul the zinc tub into the kitchen and then lug and heat enough water to fill it. All of them go to the steam bath instead, as I’ve been doing, but they go only once a week and I go every other day. They laugh at me for being so fastidious for a man, but the truth is, I’ve gotten used to being clean and I’m no longer used to small-town living in Lithuania, with its lack of indoor plumbing. When I lived here, I never noticed how the outhouse smelled, but now I do, and the odor from the chamber pots under our beds at night is also noticeable to me. I miss my landlady’s porcelain bathtub, tiled bathroom, even the gas lamps. Mrs. Horowitz’s hands are smooth and plump, even though she’s 51, my mother’s age exactly. In America, women don’t have hands like my mother’s, at least not that I can remember seeing.

I look at Mera’s hands as she tears bits off her pieces of challah and sops them in the tsholent, the Sabbath stew. She’s sitting on the end of the bench next to our father, her body twisted a little sideways so that she’s almost facing away from us. She’s slumping, with her chin resting on her hand. The look on her face is irritable. Her hands still look all right, though her nails are broken and a little dirty. It’s up to me what her hands will look like when she’s 40, whether they’ll be twisted and spotted like our mother’s or doughy and soft like Mrs. Horowitz’s. Mera doesn’t know about this. At least, I don’t think she knows. The future of her hands is not on her list of all the things she has been deprived of because her little brother has escaped to America. According to her way of thinking, I’ve gotten everything and she’s been left with the dregs of life.

“You don’t want more?” Mother pushes the bowl at me.

“Eat, eat,” my father urges, gesturing with his hand at the bowl. “Only one more week for you and then you won’t have Mama’s dumplings anymore.”

“No, no, thank you,” I say and push my plate away a little. “I’m full. I won’t even be able to eat supper later, I don’t think.” I offer my father a cigarette but he declines; he really doesn’t enjoy anything but his snuff, and even that, he hardly takes. It’s schnapps he prefers and he reaches eagerly for the bottle of Scotch I brought for him as a gift from Massachusetts. He pours shots for me and for himself.

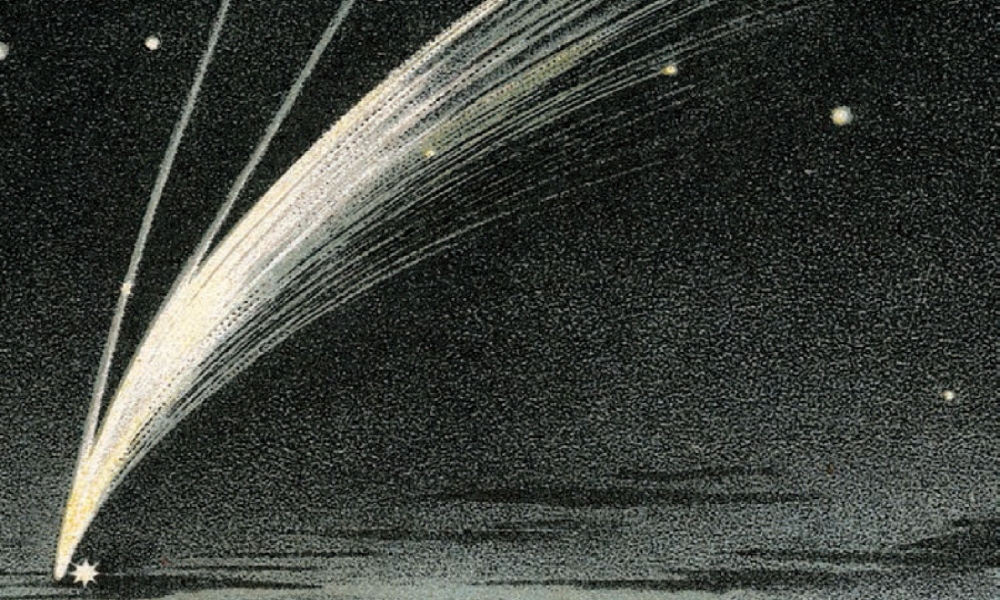

“You can’t put off your return a few more weeks?” my mother frets, frowning at the sight of me smoking on the Sabbath. “Maybe it’s not a good idea to be on the sea during the time of the star. Who knows what could happen?”

I see the shadow of a smirk on Mera’s face. Mother can’t remember the word “comet.”

“Nothing will happen, nothing will happen,” my father waves his hand at Mother, as if shooing a chicken. “Foolish wives’ tales, everything will be fine, don’t get yourself worked up.” He looks apprehensively at her, warning her with his eyes not to fall apart, not to burst into tears. Then he turns to me. “In America, they don’t believe in such nonsense, do they? There, women aren’t running to the graveyard at midnight to marry blind widows to retarded orphans, are they?” He cackles. Some of the more superstitious and older Jews have been going around in a frenzy for months, ever since January when the first comet lit up the evening sky for several nights in a row with its glowing tail. And now there is the second one, which has been visible in the sky over Lithuania for several days. My father has been making fun of his old friend, Pinkhes, for fasting, and pooh-poohs those who quote the passage from the Talmud about the star that comes only once every 70 years and makes ships go off-course.

“I have to go back, Mama,” I say, using my best smile, the one I use to charm lady customers in my store. “I have the ticket already and Louis has been running the business while I’ve been away. When I come back, it’s his turn for a vacation, to visit his parents. He has steamship tickets for June 1.”

My mother sighs and begins to stack the dishes on the table, looking distressed. As I get up to put my jacket on, I kiss the top of her Sabbath cap, crocheted and mulberry-colored. “Why don’t you wear the hat I brought you from America?” I ask her. I’m annoyed. She’s been wearing this same cap since I was a little boy.

“It’s too good for ordinary Sabbaths, my dearest,” she says. “I’m saving it for weddings or other celebrations.” When she says “weddings,” she looks meaningfully, first at me, and then at Mera. I know she realizes that if I ever do get married it will be far away in America and she won’t be there to see it. And Mera is already an old maid, with dwindling prospects. But my mother clings to her fantasies.

At the mention of weddings, Mera gives me a black look. I return her gaze defiantly. It’s not my fault that she missed the boat when it came to marriage, and that when she was younger, I was still struggling to gain a foothold in the golden land and couldn’t send much money for her dowry.

After lunch, I stroll over to the bench outside Meylekh’s store, where a few of the young men in town sun themselves and smoke. Of course, only the modern ones, the free thinkers, do this. The more religious men wouldn’t dream of lighting a cigarette on the Sabbath. I never did before I went to America. What my father accepts now, he would have smacked me in the face for back then.

There aren’t too many of my friends left now. Almost everyone, like me, has gone to America to escape the draft. I run into plenty of boys from our town over there. Those who didn’t leave got exempted for medical reasons, or through bribes, or are off in the regiments now, serving the tsar. But I don’t have to worry about being hauled off as a draft-dodger. We’ve paid off the constable to ignore my presence here during my short visit.

When I get to the bench, I see that Benya is among the small group sitting there. He doesn’t look up or greet me, and I don’t try to catch his eye. I notice he’s wearing work clothes even though it’s the Sabbath.

Benya and I were pretty close when we were children, our fathers both being cattle dealers. They took us along on market days when we were still little, and we got up to plenty of mischief together. His blond hair and blue eyes made Benya particularly popular with the peasants, especially the women, who would pinch his cheeks and give him a handful of nuts or an apple slice. They weren’t so interested in me—I was just an ordinary dark-haired little Jewish boy.

Now Benya’s no longer blond, but brown-haired, with a short beard. His skin is reddish and his nose a little swollen. He’s my age, 27, but looks older, like his late father, as a matter of fact.

“How are you, Shmuel? Good Shabbos,” Hershel greets me. “Grab a seat.” He slides over and makes room for me on the bench between him and Peysekh. “That is, if you’re not afraid to get a splinter in your fine trousers.”

I wave my hand at him dismissively, but remain standing, leaning on my walking stick. It’s true that I’ve tried to maintain my standards during my visit, that I shave every day. The men here, even the ones who are beardless, shave only once a week or so, and go around with stubble on their cheeks.

“What’s new?” I ask, adopting Hershel’s lightly mocking tone. “Who’s gone bankrupt or run away from the army? Has Golde Rivke’s Moyshe’s cow given birth to a two-headed calf?”

“They say that we’ll all be poisoned by the comet,” Peysekh pipes up. “I read in the Russian newspaper from Vilna that the comet will brush the earth with its tail and that it will shower cyanogen upon us.” He stumbles over the word “cyanogen,” saying “soynedzhenen” and looks quite anxious. I hope that my mother doesn’t hear about this; I can only imagine her hysteria.

“They wrote about this long ago in the American newspapers,” I say, laughing. “The scientists say that nothing catastrophic will happen, that there is really no need to panic.”

I feel sorry for them. They have only the primitive Russian newspapers and the stray Hebrew journal which comes months late with old news and which half of them aren’t educated enough to read anyway. We used to think Peysekh was a brilliant young man but now I imagine him standing in the streets of Lynn, Massachusetts, and gaping at quite ordinary things: paved streets, the corner mailbox, the cars. I wonder if after he stopped being a greenhorn, he would become brilliant again? Or maybe he could only be brilliant at one time and one place and that time is now over forever for him? Look at him sitting on the bench like that, his brow furrowed from too many days spent worrying about the price of flour.

But they’re all staring at me with respect, with big eyes, waiting to hear what I’ll say next. I’ve been good entertainment for them this past month. They question me closely about my life in America, especially about my store and how business is conducted in Massachusetts, a word they have a great deal of trouble pronouncing. Only Benya says nothing, just grinds out his cigarette in the dirt. In a little while, he excuses himself and leaves, clumping his way off in the direction of his house.

After I’ve spent a little while with the fellows, I say goodbye and that I’m going for a stroll. Hershel smirks at me but I don’t let on that I’ve seen. As I leave the marketplace, I am keenly aware of their eyes on me and know that they’ll start talking about me as soon as I’m out of earshot. I feel a stiffness in my back and I feel as if I’m walking unnaturally, until I turn down one of the side lanes, out of their view. I relax and swing my walking stick from time to time. I’ve been called porets, nobleman, for this. Here, only the old and lame walk with a cane, not dandy young men.

Everything looks familiar and yet unfamiliar at the same time: the low wooden houses, the dirty porch railings, the unpaved streets. These seemed so unremarkable to me when I was growing up here, but now they seem quite outlandish. The whole town seems small, not like the place I’ve thought about during my lonely nights in America. At night in my bed, all this seemed life-sized to me, not the way it looks to me now: tiny, like one of those small snapshots taken with a Brownie. Now that I’ve come back, nothing seems real to me. And even Lynn now seems unreal, like a dream, something I maybe made up.

When I get to the last house on the street, I notice that all the windows are open. A grayish white kitten sits on one of the windowsills, licking its paw, squinting at me amiably. Why do cats and goats have similar eyes, I wonder. Both have slits for pupils but goats’ are sideways and the cats are straight up and down. I never have these sorts of thoughts in Lynn; it’s too busy there. And there aren’t any goats. It seems odd, somehow, that there are cats both here and where I now live, but not goats. Why one and not the other? I know that there is a perfectly logical reason for this, but for the moment I can’t think of it.

I whistle one of the jingles that were popular during the last American election, “Get on a Raft with Taft,” and sidle over to the window. Esther is there in the room, sitting before a mirror, putting some pins into her hair. Because of the whistling, she already knows I’m there but pretends to have just caught sight of me in the mirror. She bursts into giggles.

“Sam!” The way she says my American name sounds like Sem. “What’s wrong with you? Don’t you know it’s not appropriate to look into a lady’s boudoir?” But she isn’t offended, not really. In fact, she gets up and comes over to the window and leans over the sill so that her face is only about a foot away from mine.

“What are you accusing me of, Esther?” I pretend to be offended. “Really, I was just passing by and suddenly realized that this was your house, and I wondered if you were at home.”

She plays along with the joke and leans further over the sill, her raisin-like eyes smiling into mine. I’m still not sure what I see in her, why I’m so drawn to someone who, objectively speaking, is not even as pretty as some of the girls I’ve gone with in Lynn. But she teases like an American girl and has some style. She reads Russian, and some German and French too, supposedly. Snobbish and stuck-up, Mera calls her, sneering at her habit of using French words, like “adieu,” instead of “goodbye.”

Yes, I muse, “adieu” won’t go over in America either, and then I catch myself. It’s not as if I’ve made up my mind to give her father a steamship ticket for her to join me in America. Maybe, after all, I should just go and leave her to Benya. It’s not as if she has a huge dowry to offer. It’s been a terrible year for grain and despite Esther’s ruffles and gloves, the family can’t be doing all that well. I heard that Kalmen had to sell the plot in Jesna he had been leasing to a peasant.

Meanwhile she’s twinkling knowingly at me, perhaps taking my silence to mean that I’m shy and tongue-tied in her presence. I lightly flick my finger at a wisp of her hair that has escaped the pins, eliciting more giggles. She slaps at my hand and soon we are grappling with each other over the windowsill like ten-year-old children, like a brother and sister. It seems that Esther doesn’t mind acting silly. I can picture her in a fine parlor in Lynn, laughing merrily at the witticisms of a group of gentlemen.

With a final push of her hands, Esther moves away from me and back from the window. I take a step back, too, doff my hat, and bow. Then I get to what, after all, was the purpose of my visit. “Are you coming to the river tonight, Esther?” I ask. During the past week, groups of townspeople, mostly young men, have been going out to a spot on the riverbank to look at the comet.

Esther can’t stop the smile from spreading on her face. “I don’t know. I’ll have to ask my father.”

“You’re not afraid, are you?” I gently mock her. “You’re not one of those who are afraid that the comet means the world is going to end?”

“Of course, not, Sam,” she says, suddenly looking uncertain. “I’m not old-fashioned like that. And if you say there’s nothing to fear, then I trust you. My father trusts you, too. In fact, just the other day, he was telling my brother what a clever man you’ve become and that he hopes that Leyzer will grow up to be as successful as you are. But I’ll have to get his permission to go out in the nighttime. There are non-Jews there, too, I hear.”

“Well, I hope I’ll see you there,” I say, giving her my most serious look. “I’ll be there for certain and would be happy to escort you home safely afterwards.”

I know that she will run to ask her father as soon as he wakes up from his nap and that there will be no problem getting him to let her go. In fact, I can picture Kalmen’s glee that things are progressing this way. He will pat himself on the back for allowing Esther to all but break off her engagement to Benya. He thinks, now he won’t have to settle for a lame cattle dealer as a son-in-law, but instead, will have in the family a wealthy man, a store owner.

I say goodbye and walk off, thinking ahead to the evening. I picture myself embracing Esther and kissing her and it excites me. Then my fantasy shifts to an image of Esther looking deep into my eyes and I feel nervous for some reason. I’ve known Esther since she was a baby and I was a young boy. But what is “since”? Does it exist when you haven’t known each other continuously, when there is no passage between the breaks in time? Enough of these silly questions to myself, I think, shaking my head. Since I’ve been back I’ve been like a crazy person, always talking to myself, though at least I’m not doing it out loud.

Mother wails and buries her face in her apron. “God in heaven, don’t do it! I warn you, children, don’t do it!” She collapses onto the settee, sobbing hysterically.

This is how she reacts on hearing that not only I, but also Mera, are leaving to go out to the riverbank to join the crowd of comet-watchers.

“It’s bad luck, it will bring no good!” she all but shrieks.

“Khaya, what is with you?” My father pleads. While my mother is emotional and often cries, it is usually quietly. Never before has she broken down this way. “What is this foolishness? Nothing will happen to the children for gazing at a star.”

“You’re wrong! You’re wrong!” She refuses to be consoled. “I’ll never see him again; this is it!”

I wonder if she is becoming senile, if she is confusing me going out this evening with my departure in a week. Of course, then it will actually be true: She probably won’t ever see me again. She and my father aren’t that young; their health isn’t that good. It’s not easy making the trip back home and this was the first time I’ve managed it in the almost ten years I’ve been gone.

“Pull yourself together, my dear,” my father says. “I’d go myself to see God’s wonder but I’m too old to go sit on a damp riverbank so late at night. Let the young people go. Go!” He waves his hand at us. “I’ll stay here and take care of Mama.”

Mother still has her head buried in the settee and all she does is moan.

“Mama, don’t worry,” I say, as nonchalantly as possible. “I’ll keep an eye on Mera, make sure that she doesn’t get into any trouble.”

Mera shoots me an enraged look but she clamps her lips shut, looking as if she’s swallowing what she really wants to say. She knows that if it wasn’t for me, she wouldn’t be going out tonight. Though she’s 30 years old, she’s still an unmarried girl, and my father is only letting her go out to such a risqué gathering because her little brother, the man of the world, will be with her.

As we pick our way over the rutted street, I can feel her seething beside me. I look over at her, and though it’s getting dark, I can see her scowl. “Come on, Mera,” I say. “Don’t spoil everything. Let’s have a good time tonight.”

“A good time!” she sputters. “You can have a good time. But for me there will never be a good time!”

“So all times are bad for you, have always been bad for you, and will always be bad for you.” I sigh. These are the sorts of outbursts that I’ve been treated to for weeks now, a live version of the bitter letters she’s been sending me for years. I’ve been avoiding just this conversation with her since I came home. “What can I do about it?”

“What can you do about it, what can you do about it,” she repeats. “A decent person would have done something long ago.”

“Come on now,” I say, once again trying to reason with her. “How can I bring you over to America? Maybe before, when our parents were younger, but you didn’t want to go then. Now, there’s no one else to stay here and take care of them. I can’t bring you all over. I just opened the store and besides, Mama won’t go. She’s terrified of the voyage.”

There is nothing she can say to this, I think, and I’m grateful that it’s now dark enough so that I can’t see the look on her face. I should leave it at that, but then I hear myself continuing, “And you think it was easy to be over there all alone in a strange land without my parents when I was young? It was terrible, I thought I’d kill myself.” There is a catch in my voice that surprises me.

“But what could we do?” Mera sounds surprised. Now, it’s her on the defensive. “Otherwise, you would have had to go serve.”

“Other people’s fathers managed to buy them out.” My teeth are clenched and I can hear my heart start to beat faster. “It’s not so terrible to have your mother and father with you, you know.”

I hear Mera stumble over something next to me in the dark. We both stop walking. In the gloom, I can hardly see her face, and in fact, it doesn’t seem like a face at all. It’s like when we were children in a dark room and her face would change until it didn’t look human. I would see a goat’s head in place of her face, or a demon’s. Whoever this family was that I longed for as a homesick teenager, I don’t know them now. “Why did you call off the match?” I ask her. They had written me about the last match, the one to Shmerl Berl’s son Moyshe and then that it had been called off, but not the reason why.

“He smelled bad,” Mera says flatly. “Like cheese, spoiled cheese.”

I giggle. “What! Like cheese. After all, he was a dairy man,” I tease.

I feel Mera smiling in the dark. “Yes, but it was something worse than that; I don’t know. He also breathed loudly through his mouth and his nose was stuffed up all the time.”

I laugh. “Good! I’m glad I don’t have a smelly cheese as a brother-in-law.” We’re back on the surface now; I’ve bubbled my way back up from the grief. We’re both giggling.

Her giggles trail off. “You don’t have any brother-in-law,” she says, sounding sour again. “Would I be able to find a husband in America at my age?”

“Probably not,” I answer her, noticing that we’re almost at the river now. Before she can say anything in return, I bound off, heading for noise and light. She stumbles behind me. Life has passed her by, and it isn’t my fault.

At the river, there is quite a crowd, as if the whole town has come out. We’re in the spot called “Kiril’s Inn,” though who Kiril was and when there was ever an inn here, no one remembers—it was probably centuries ago. There are several bonfires and those who stand near them are lit up by the glow, tinted brownish orange like expensive portrait photographs. Sparks whirl festively around them.

I spot Esther whispering to another young woman but don’t immediately go over to her. I study her, take a good look at her, in a way that I can’t do when she knows I’m looking at her. How she holds her head, what her profile looks like, and her body, of course, the way her corsets define her bust and waist and her skirts drape over her hips. Having worked in the garment industry so long, I’m an expert in women’s clothes and I mentally redress her in what the best women in Lynn have been wearing this year.

Suddenly, I feel someone’s eyes on me. Looking to the left I meet the eyes of Benya, who is standing away from the fire, in the shadows. He’s gazing steadily at me; he’s been watching me watch Esther. There’s no expression in his eyes, or if there is, I can’t read it. I drop his gaze and look off to my right. There is Mera, standing about 20 feet away with her arms crossed, glowering at me. The two of them stand still like the angels and the flaming sword in Bereyshis, Genesis, who would not let Adam and Eve back into the Garden of Eden to eat of the Tree of Life. The light from the fire flickers in their eyes.

We all stand like this for a few seconds. Then I take off, walking calmly away toward the river, where I see some of the men sitting on the big laundry rock, and where the sound of glasses and bottles clinking can be heard. Perhaps Hershel and Peysekh are there. But halfway there, I stop and light a cigarette. The sky is quite dark now, and people are beginning to point at the bright streak in the sky. It’s a moonless night, so the stars are particularly bright. I feel the cool, damp air of the river settle on my jacket, and the heat of the fire and of Benya and Mera’s hatred fade away behind me.

I walk back toward where Esther is standing. She’s not looking at the sky, is still whispering with her friend.

“Miss Esther.” I stop and bow. “May I have the pleasure of accompanying you on a stroll to the river?”

Her friend backs off, all at once, like a skittish animal. She doesn’t stay to be introduced to me, just goggles at me from a distance. No doubt she’s thinking, so this is the famous Sem I’ve been hearing about.

For once, Esther is quiet and doesn’t offer a witticism in response to my bow. Her eyes shine, but she also looks a little scared as she gives me her arm and we walk toward an empty patch of riverbank in full sight of Benya and Mera. And they’re not the only ones who notice us.

When we get to the river away from the crowd, it’s quieter. The comet is quite bright now, hanging in the sky to our north, its tail slightly curving like a smirk. I wonder how it can be moving when it looks so still.

“Just think,” Esther says, “the next time it visits, we won’t be around to see it. Or we’ll be very old.”

“Who can imagine 70 years from now?” I say lightly, as I lead her down to the shore behind a small hill that hides us from view. She murmurs in agreement and picks her way gracefully in her kid shoes over the grass and sand and rests her hand lightly on my forearm.

When we are out of sight of the townspeople, I take her by the shoulders gently and turn her to face me. “Esther,” I sigh and kiss her on the lips. I’m pleased that she closes her eyes, that she has a proper sense of romance, not staring into my eyes intensely as I had feared. She’s playing her part quite well.

And now comes the moment when I should play mine, when I should ask her to marry me, to come back with me to America or to follow me in a couple of months. What will she be when we emerge from behind this rock, a lucky girl on the way to America, or a disgrace, who will be shunned and snickered about? As we say at weddings, siman tov and mazel tov, may this be a good omen and may the stars grant us good fortune. Whether I play my part or not, I have nonetheless created a legend, made Esther the girl of the comet. Seventy years from now, will they still be talking about us here? “Esther,” I say, and then I stop. The next 70 years hang in the air between us and the comet remains frozen in the sky.

Roberta Newman lives in New York and is a writer and scholar specializing in Jewish history and culture, who has served as a researcher for many documentary film, exhibition and book projects. She is Director of Digital Initiatives at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research and is the co-author, with Alice Nakhimovsky, of Dear Mendl, Dear Reyzl: Yiddish Letter Manuals from Russia and America (Indiana University Press, 2014).