“The silk-hat banker Jacob Schiff, concerned about the conditions on the East Side of New York (and embarrassed by the image it created for New York’s German Jews), pledged half a million dollars in 1906 to the Galveston Project, which helped direct more than ten thousand Eastern European migrants through Galveston into the South and Southeast.” —The Provincials: A History of Jews in the South, by Eli N. Evans.

And who is Jacob Schiff that he should be embarrassed by my Uncle Ben Daynovsky? My father’s family certainly came to Missouri from Eastern Europe around 1908 via the port of Galveston, and, I’ll admit, that route struck me as rather odd every time we read in history class about how all the tired, poor, huddled masses swarmed into this country through Ellis Island. It never occurred to me, though, to explain it all by assuming that Jacob Schiff found my family not only tired and poor and huddled but also embarrassing. I always considered the Galveston passage to be one of those eccentricities of ancestral history that require no explanation—the kind of incident we hear about so often from people who have family trees concocted for themselves by wily English genealogists. (“For some reason, the old boy showed up late for the Battle of Hastings and therefore survived to father the first Duke, and that’s why we’re here to tell the tale.”) I have always been content—pleased, really—to say simply that my grandfather (Uncle Ben’s brother-in-law) happened to land in Galveston and thus made his way up the river (more or less) to St. Joseph, Missouri, leaving only sixty miles or so for my father to travel in order to complete what I had always assumed to be one of the few Kiev-Galveston-St. Jo-Kansas City immigration patterns in the Greater Kansas City area.

The first issue of Moment (1975)

To be absolutely truthful, it occurred to me more than once that my grandfather and Uncle Ben might have caught the wrong boat. I have never heard my mother’s views on the subject, but I have always assumed that she would believe that the use by my father’s family of a port no one else seemed to be using had something to do with the stubborness for which they retain a local renown in St. Jo. As I imagine my mother’s imagining it, my grandfather would have fallen into an argument with some other resident of Kiev (or near Kiev, as it was always described to me, leading me to believe as a child that they came from the suburbs) about where immigrants land in the United States. The other man said Ellis Island; my grandfather said Texas. When the time came to emigrate, my grandfather went fifteen hundred miles out of his way in order to avoid admitting that he was wrong. My grandfather died before I was born, but my Uncle Ben is still living in St. Jo; he has lived there for sixty or seventy years now, without, I hasten to say, a hint of scandal. Stubborn, O.K. But I simply can’t understand how anyone could consider him embarrassing.

This story originally appeared in the May/June 1975 inaugural issue of Moment and is reprinted here in honor of the magazine’s 45th anniversary. Calvin Trillin received Moment’s first Mitchel and Gloria Levitas Literary Journalism Award at Moment’s 2020 gala, “Rising to the Moment.”

“Who is Jacob Schiff that he should be embarrassed by my Uncle Ben Daynovsky?” I said to my wife when I read about the Galveston Project in The Provincials.

“You shouldn’t take it personally,” my wife said. “I’m not taking it personally; I’m taking it for my Uncle Ben,” I said. “Unless you think that Jacob Schiff’s descendants are embarrassed by my moving to New York instead of staying in our assigned area.”

“I’m sure Jacob Schiff’s descendants don’t know anything about this,” my wife said.

“And who are they that they should be embarrassed by my Uncle Ben Daynovsky?” I said. “A bunch of stockbrokers.”

“I think the Schiffs are investment bankers,” my wife said.

“You can say what you want to about my Uncle Ben,” I said, “but he never made his living as a moneylender.”

I always considered the Galveston passage to be one of those eccentricities of ancestral history…It never occurred to me, though, to explain it all by assuming that Jacob Schiff found my family not only tired and poor and huddled but also embarrassing.

I’m not quite sure how my Uncle Ben did make his living; I always thought of him as retired. As a child, I often saw him during Sunday trips to St. Jo—trips so monopolized by visits to my father’s relatives that I always assumed St. Jo was known for being populated almost entirely by Eastern European immigrants, although I have since learned that it had a collateral fame as the home of the Pony Express. Until a few years ago, Uncle Ben was known for the tomatoes he grew in his backyard and pickled, but I’m certain he never produced them commercially. A few years ago, when he was already in his 80s and definitely retired, Uncle Ben was in his backyard planting tomatoes when a woman lost control of her car a couple of blocks behind his house. The car went down a hill, through a stop sign, over a meridian strip, through a hedge, and into a backyard two houses down from Uncle Ben’s house. Then it took a sharp right turn, crossed the two backyards, and knocked down my Uncle Ben. It took Uncle Ben several weeks to recover from his physical injuries, and even then, I think, he continued to be troubled by the implications of that sharp right turn. One of his sons, my cousin Iz, brought Uncle Ben back from the hospital and said, “Pop, do me a favor: next time you’re in the backyard planting tomatoes, keep an eye out for the traffic.” “First that car makes a mysterious right turn and now he’s being attacked by a gang of stockbrokers,” I said. “It hardly seems fair.”

“There’s something very interesting about the Schiffs listed in Who’s Who,’’ I said to my wife not long after our first conversation about the Galveston Project. “I think you’d better find yourself a hobby,” she said. “As a matter of fact, I’m thinking about taking up genealogy,” I said. “But listen to what’s very interesting about the Schiffs listed in Who’s Who: the Schiffs who sound as if they’re descendants of Jacob Schiff seem to be outnumbered by some Schiffs who were born in Lithuania and now manufacture shoes in Cleveland.”

“What’s so interesting about that?”

“Well, if Jacob Schiff thought people from Kiev were embarrassing, you can imagine how embarrassed he must have been by people from Lithuania.’’

“What’s the matter with people from Lithuania?” she said.

“I’m not sure, but my mother’s mother was from Lithuania and my father always implied that it was nothing to be proud of,” I said. “He always said she had an odd accent in Yiddish. I’m sure he must have been right, because she had an odd accent in English. Anyway, Who’s Who has more Lithuanian Schiffs than German Schiffs, even if you count Dorothy Schiff.”

“Why shouldn’t you count Dorothy Schiff?” my wife said.

“Isn’t she the publisher of the New York Post?’”

“Yes, but why is it that she is publisher of the New York Post?”

“Well, I suppose for the same reason anybody is the publisher of any paper,” my wife said. “She had enough money to buy it.”

“Only partly true,” I said. “She is the publisher of the New York Post because several years ago, during one of the big newspaper strikes, she finked on the other publishers in the New York Publishers Association, settled with the union separately, and therefore saw to it that the Post survived, giving her something to be publisher of.” “Since when did you become such a big defender of the New York Publishers Association?” my wife said. “My Uncle Ben Daynovsky never finked on anybody,” I said.

“Maybe that passage in The Provincials was wrong,” my wife said when she came into the living room one evening and found me reading intently. “Maybe Schiff gave the money to the Galveston Project just because he wanted to help people like your grandfather get settled.”

“I’m glad you brought that up, because I happen to be consulting another source, “ I said, holding up the book I was reading so that she could see it was Our Crowd, which I had checked out of the library that day with the thought of finding some dirt on Jacob Schiff. “Here’s an interesting passage in this book about some of the German-Jewish charity on the Lower East Side: ‘Money was given largely but grudgingly, not out of the great religious principle of tz’dakah, or charity on its highest plane, given out of pure loving kindness, but out of a hard, bitter sense of resentment, and embarrassment and worry over what the neighbors would think.’”

“I don’t see what you hope to gain by finding out unpleasant things about Jacob Schiff,” she said. “Historical perspective,” I said, continuing to flip back and forth between the Jacob Schiff entry in the index and the pages indicated. “Did you know, by the way, that Schiff had a heavy German accent? I suppose when it came time to deal with the threat of my Uncle Ben, he said something like, ‘Zend him to Galveston. Zum of dese foreigners iss embarrassink.’”

When I told her that Schiff used to charge people who made telephone calls from his mansion—local calls; I wouldn’t argue about long distance—she said that rich people were bound to be sensitive about being taken advantage of.

“I never heard you make fun of anybody’s accent before,” my wife said.

“They started it.” “My Uncle Ben never associated with robber barons like Gould and Harriman,” I said to my wife a few days later. “When it comes to nineteenth-century rapacious capitalism, my family’s hands are clean.” My wife didn’t say anything. I had begun thinking that it was important that she share my views of Jacob Schiff, but she was hard to convince. She didn’t seem shocked at all when I informed her, from my research in Our Crowd, that Schiff had a private Pullman car, something that anyone in my family would have considered ostentatious. When I told her that Schiff used to charge people who made telephone calls from his mansion local calls; I wouldn’t argue about long distance—she said that rich people were bound to be sensitive about being taken advantage of. “One time, he was called upon to give a toast to the Emperor of Japan, and he said, ‘First in war, first in peace, first in the hearts of his countrymen,’” I said.

“It’s always hard to know what to say to foreigners, “ she said.

“What about the checks?” I said one evening.

“What checks?” she said.

“The checks Schiff had framed on the wall of his office,” I said.

“I can’t believe he had checks framed on the wall of his office,” my wife said.

“I refer you to page one hundred fifty-nine of Our Crowd,” I said. “Schiff had made two particularly large advances to the Pennsylvania Railroad, and he had the cancelled checks framed on his wall.” “Did he really?” she said, showing some interest. “One of them was for $49,098,000,” I said.

“That was kind of crude,” she said.

“Not as crude as the other one,” I said. “It was for $62,075,000.”

“I think that’s rather embarrassing,” she said.

“I would say so,” I said, putting away the book. “I just hope that no one in St. Jo hears about it. My Uncle Ben would be mortified.”

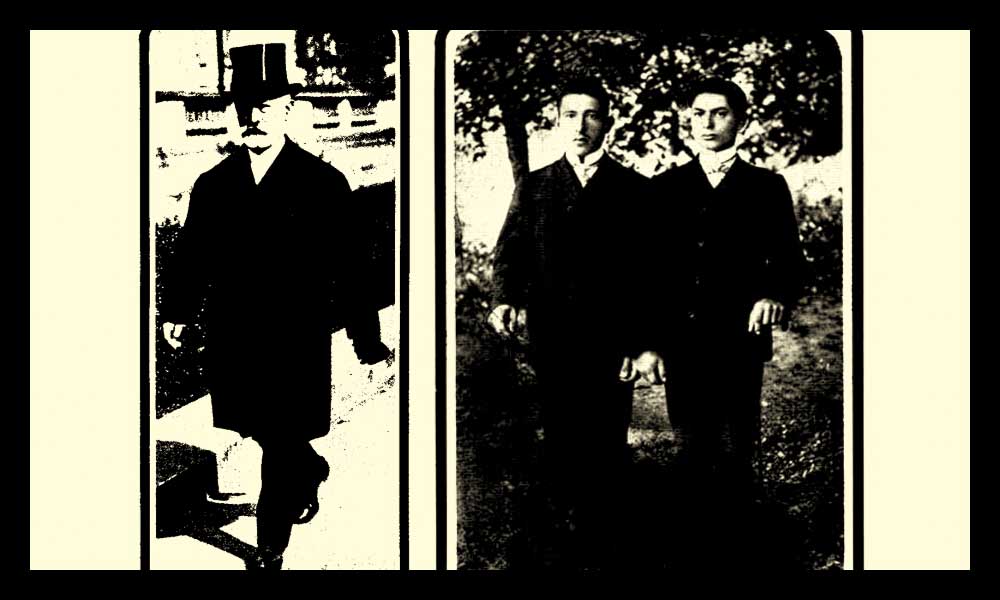

Opening picture: (From left): Jacob Schiff; Ben Daynovsky and another family member. (Photo credit: Courtesy of Calvin Trillin, NY Public Library)

Moment Magazine participates in the Amazon Associates program and earns money from qualifying purchases.

Puerto Rico had a Jacob Schiff that no one likes to talk about because he was thought of as a great man.

Luis Munoz Marin was the first native Puerto Rican elected to the office of governor on the Island. He copied FDR’s New Deal and helped modernize and industrialize Puerto Rico. He solved a self-identified over population problem on the Island by helping companies hire laborers for farms and factories. Companies would transport workers from the Island to farms and factories in the urban northeast, industrial midwest and growers of lettuce, apples etc.

He was hailed as a visionary, but like Schiff he wanted to remove people in his own community who he considered to be an embarrassment. The corruption and abuse underlying Marin’s program of pushing people to leave their homes and families has not been fully exposed.

Kudos to Mr. Trillin for bring Schiff down a peg and then some.