In the wake of the November 1947 UN vote on the partition of the British Mandate of Palestine, while Jews across the country were celebrating, David Ben-Gurion remained sober. Preoccupied by the imminent struggle to secure Jewish sovereignty in Palestine, he meticulously created a list of necessities for the fledgling state. The country would need an army, an airport, a civil administration and also a name.

A mere two days before the new state declared independence, with hundreds dead from Arab-Jewish violence and enemy armies besieging Jerusalem, the Jewish National Council, then the primary executive body of Jewish Palestine and led by Ben-Gurion, met to create the Declaration of Independence. Among pressing military and logistical concerns, it was incumbent upon the council to come up with a name.

Initially, the most popular name for the would-be state was Judea, which derives from Judah, the fourth son of Jacob. In Genesis, Jacob blesses Judah as the leader of the tribes, before whom his enemies will flee and his brothers submit. This blessing was realized when, after the death of King Solomon and the collapse of the biblical Kingdom of Israel, the Kingdom of Judah emerged as its primary successor. But Judah was eventually invaded by the Babylonian Empire, its Temple destroyed and its people scattered. Some 70 years later, in the 6th century BCE, with the state reforged as Judah and later as the Greco-Roman Judea, Jews built the Second Temple and restored the kingdom. Various incarnations of Judea surfaced throughout the Alexandrian conquests, the Maccabean revolt and ultimately the Jewish-Roman Wars.

Given this storied and emotionally salient history, it made sense that the members of the National Council would consider Judea as a name for their state. Indeed, “most people in the international community thought the name would be Judea because it was the last sovereign Jewish state in antiquity,” notes Martin Kramer, a Middle East historian at Tel Aviv University. However, the name was rejected, primarily on the grounds that it was irredentist—that is, that it advocated for the reclamation of lost historical territory—and that it might inflame an already volatile situation. “Under the partition plan, much of [ancient] Judea was not in the modern state envisioned by the United Nations, and Ben-Gurion was trying to make a vision of Israel as broad as possible,” says Gil Troy, a professor of history at McGill University. Ben-Gurion saw the danger in the territorial claim inherent in the name Judea. Neither he nor the council wished to further antagonize the international community, so they rejected it.

Another popular suggestion for the name of the new state was Zion. The logic was simple: Zionism is the ideological project and political pursuit of establishing a Jewish state, so Zion would be the state. Kramer notes that “in the Bible, Zion sometimes meant all of Israel” but that “Har Tzion, Mount Zion, was outside the Jewish state licensed by the partition plan.” This name was likewise rejected in the interest of avoiding provocation, as the city of Jerusalem, where Mount Zion is located, was designated an international city under the UN partition.

The name Ever was also considered. Derived from Ivri, the Hebrew word for “Hebrew,” Ever had the benefit of not representing a territory. However, writer Moshe Brilliant, in a 1949 Palestine Post article on the National Council’s deliberations, explained that “no one liked it.”

In addition to those names considered by the council, there were also some omitted from the conversation. The most prominent of these was the name Palestine. After the third Judean war and the destruction of the Second Temple, the Romans changed the name of the province of Judea to Syria Palaestina, derived from the Greek name for the region, Philista, meaning “land of the Philistines.” Given that the Philistines were the Israelites’ ancient enemy, it’s unclear whether the Romans merely picked the Greek word for the region or whether the choice was made out of spite. In the following centuries, as the land passed from the Byzantines to the Arabs to the Ottomans, it retained this new name in various incarnations, including “Palestine.”

ISRAEL WAS NOT CONSIDERED AS A NAME FOR THE NEW JEWISH STATE UNTIL LATE IN THE DELIBERATIONS.

In the years before the establishment of the state, when Jews were making aliyah, the common term for the region, even among Jews, was Palestine. Historian Gil Troy notes how the word Palestine “started to have a certain magic to Jews in the 1880s, much more so in the 1920s, and certainly in the 1940s.” The Zionist movement employed the word in a variety of contexts. Theodor Herzl himself, in his 1896 treatise The Jewish State, declared that “Palestine is our ever-memorable historic home. The very name of Palestine would attract our people with a force of marvelous potency.” Despite Herzl’s endorsement, this name may have been viewed as a Roman or imperial designation, having been used by non-Jewish regimes in the region for 2,000 years. In addition, the name Palestine could also have been seen as maximalist by referencing the whole of the British Mandate. Moreover, Ben-Gurion’s conception of Zionism centered on the idea of rebirth, whereas the name Palestine would emphasize continuity.

An obvious and popular option was Eretz Yisrael. Dating back to biblical times, Eretz Yisrael, Hebrew for “the Land of Israel,” has denoted a number of geographical and political entities in the area of modern Israel. During the British Mandate, it was even the country’s official Hebrew name, appearing on letterheads and currency. Given Eretz Yisrael’s historical and religious significance, the council considered it for the name of the state. However, since it had been used as the name for the whole of mandatory Palestine, the name could also have implied territorial maximalist aspirations and so was rejected.

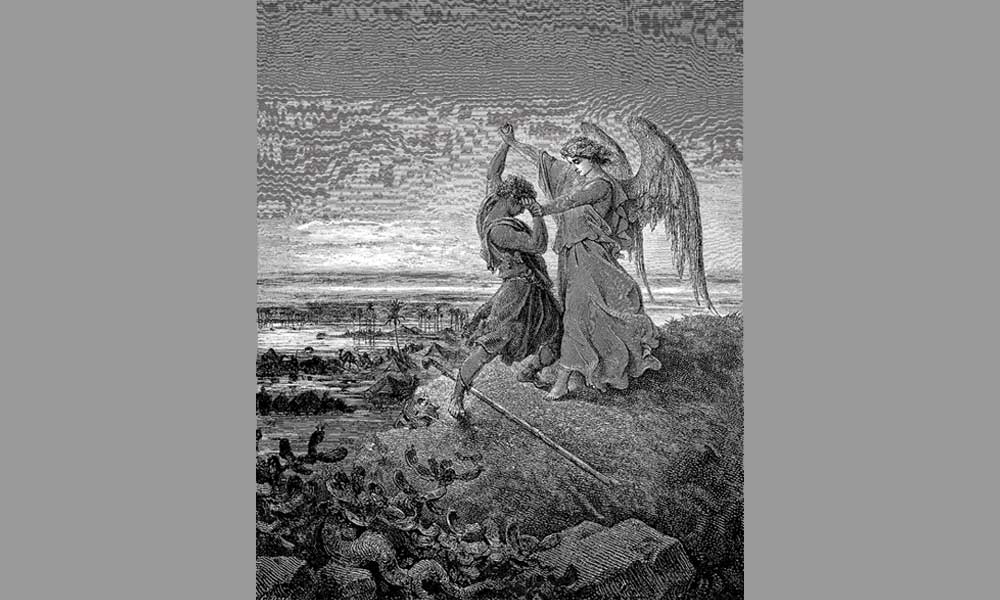

Distinct from the concept of Eretz Yisrael is Bnei Yisrael, the children of Israel. And while never considered for the name of the state itself, Bnei Yisrael, rather than Eretz Yisrael, is the origin of the word Israel that would be used as the state’s name. Israel’s foundational biblical narrative describes how Jacob, after wrestling with and overcoming an angel, convinces God to confer upon him the name of Yisrael, or Israel. Just what exactly that name means is a matter of no small theological and etymological debate, although most often it is translated as “struggle” or “struggles with God.” According to Jack Bemporad, rabbi and professor of interreligious studies at the Pontifical University in Rome, “Jacob has contended with God and with man and has overcome, and therefore he is called Israel. But from then on, it’s basically given to the descendants of Jacob, in other words, the children of Israel.” And indeed, most subsequent biblical invocations of the word Israel refer to the children of Israel, Bnei Yisrael, rather than either Eretz Yisrael or the patriarch himself. “Israel appears about 2,400 times in the Bible, but the Land of Israel only a few times,” notes Kramer. “Israel in the Bible means the people or house or children of Israel—the people.”

Israel was not considered as a name for the new Jewish state until late in the deliberations. Partially as a result of its historical ambiguity, Ben-Gurion and the members of the National Council saw Medinat Yisrael, the State of Israel, as a relatively benign choice. “Israel had the benefit of referencing the people, not the land,” says Kramer. Future Labor Minister Ze’ev Sharef, in Brilliant’s 1949 article, explained that the councilors didn’t particularly like the name; they found it to be clunky and aesthetically displeasing. Regardless, the end of the mandate was imminent, and the council had more pressing matters to attend to. In his book Three Days, Sharef recounts how, “by a majority vote and in the absence of any other suggestion,” the council approved the name. Two days later, at the Tel Aviv Museum, Ben-Gurion declared the independence of the state of the Jewish people, the State of Israel.

The significance of the word Israel has changed over time as its use has proliferated. Legendary Israeli writer Amos Oz once noted, “Israelites belonged to the land of Israel, but Jews, from the very beginning of this collective title, inhabited a wider world.” And while diaspora Jews spent millennia as Bnei Yisrael, with the realization of Zionism and the return to Eretz Yisrael, this process has, in many ways, reversed itself and become more like Oz’s description. Today, more often than not, Israel does not mean the people of Israel, but the people and the State of Israel. And while, in the 75 years since Ben-Gurion and the National Council selected the name, the relative ideological relationship between Israel as a people and a territory has waxed and waned, the fundamental tension between the two has remained the same. What the next 75 years will bring remains to be seen.

“The preparations of the heart belong to man, but the answer of the tongue is from the Lord.” & “A man’s heart plans his way, but the Lord directs his steps.” (Proverbs 16:1, 9) The Lord had it all planned out. After all, He is sovereign!

Thank you for this excellent article.

Thank you for the history of the name of our homeland, I learned a lot, and thank G-d both the Land and People arear Bin known as Israel.

No small coincidence that my name is Yisrael bar Ben Yamin.

CORRECTION for a Typo

Thank you for the history of the name of our homeland, I learned a lot, and thank G-d both the Land and People are known as Israel. No small coincidence that my name is Yisrael bar BenYamin.