When the left and the right talk about religion in America, they often seem nowadays to be describing different countries. Liberals—in what was till recently mainstream conventional wisdom—will tell you that the American commitment to religious freedom, pluralism and a wall of separation between church and state were among the nation’s founding values and have made it a beacon ever since. To many conservatives, though, concepts such as the church-state wall are recent add-ons to a nation founded by devoutly religious leaders and built on Christian principles, principles now under constant attack from secular elites, contraceptive mandates, gay rights and the “war on Christmas.”

Steven Waldman started writing Sacred Liberty: America’s Long, Bloody, and Ongoing Struggle for Religious Freedom because he wanted to figure out whose story was right. Back when he was editing Beliefnet, a multifaith religious news site he co-founded in 1999, he says, “Nearly every day I would get an email from some advocacy group quoting a Founding Father to prove a point—but they were diametrically opposite points on different days. Sometimes the same quotes. Certainly the same Founding Fathers. I knew the quotes were being manipulated, but I had to figure out how.” His earlier book, Founding Faith, focused on just the Founders and what they believed; this one covers the whole increasingly contested narrative of American religious history. The result is a master narrative that lets readers fit the distortions and misperceptions of both sides—and yes, both sides have some—into informed perspective.

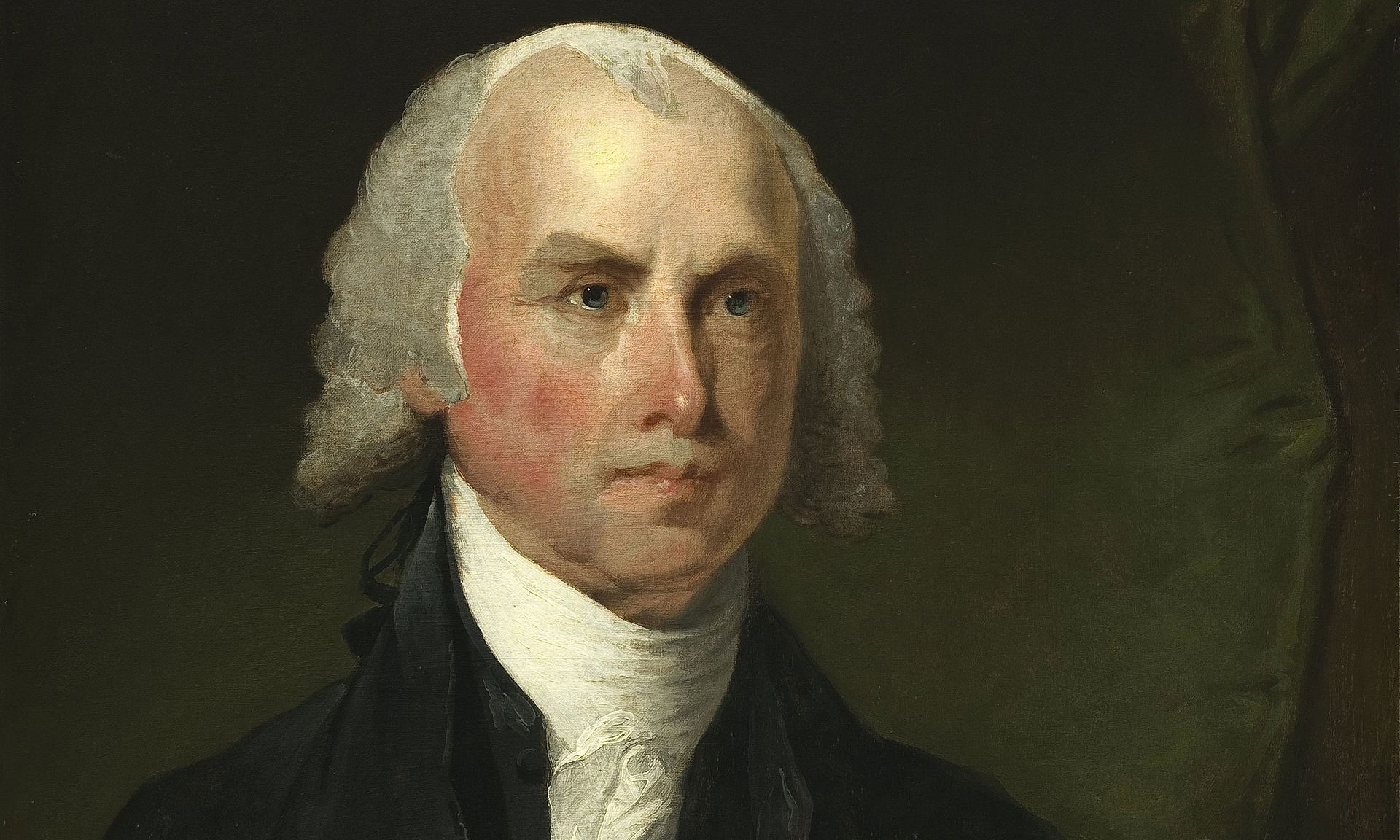

It’s also a narrative filled with surprising nuggets of American history—who knew that Dwight D. Eisenhower was raised a Jehovah’s Witness?—and rich in counterintuitive insights into just how gradual and uphill the struggle against religious bigotry has been. The book opens with the violent repression of a Baptist minister by Anglicans, in the Virginia Colony in 1771, for the crime of preaching in public—just up the road from the home of James Madison, who had known evangelicals at the College of New Jersey (later Princeton) and was deeply influenced by their persecution. Madison devised groundbreaking legal protections for freedom of religion, but even so, Protestants later united to persecute Catholics; Protestants and Catholics were joined in their distaste for Mormons; and not until the ravages of World War II did Christians see Jews as full public partners in “Judeo-Christian” culture.

Most recently, Waldman says he’s alarmed by the level of bigotry faced by Muslims—often unnoticed by those who consider themselves “persecuted” by, say, gay couples wanting wedding cakes, but who see all Muslims as terrorists and oppose the construction of mosques. Moment opinion and books editor Amy E. Schwartz spoke with Waldman about his new book and American religious history.

The idea that so much of American religious history is about anti-Catholic sentiment struck me as fascinating.

Yes—even the settling of the West, it turns out, for many Americans was a fight between Protestants and Catholics as to who would settle it first. And the religious leaders used military metaphors, like, “We have to marshal our forces on the citadel of the Mississippi River to make sure that the Catholics don’t get the high ground.” This continues in various forms up into the 20th century.

It goes all the way back. One thing I really hadn’t thought about was that when the first settlers in America came, it was only 50 years after Martin Luther’s death. We tend to think of America as being pretty long after the Protestant Reformation, but it really wasn’t. It was a proxy fight, and it carried over. You read these quotes from Founding Fathers like John Adams and Alexander Hamilton, who are otherwise eloquent defenders of freedom, and they’re saying Catholics are monsters and calling Catholicism “the whore of Babylon.” How could they not see the disconnect there? I think you have to get into the mindset that they were part of a generation that was in effect still fighting the religious wars.

And then it continues all down through American history. It’s interesting—I had been raised fully aware of the dual loyalty attacks against Jews, but I hadn’t really thought of it as much from the perspective of other religious groups. The language wasn’t quite the same, but in effect, when you think about it, one of the main attacks on Catholics throughout most of American history was a dual loyalty claim.

In the book, you tell a story about a photo of the newly constructed Holland Tunnel in Manhattan in the 1920s.

During the 1928 election campaign, the Ku Klux Klan circulated that photo widely to newspapers, saying that it was the tunnel through which the Pope was going to come and run America if the Catholic candidate, Al Smith, became president. Smith was forced to state his position on every papal encyclical and statement, on the grounds that he would have dual loyalty, that he was going to have to take orders from the Pope.

The anti-Catholic stuff shows up in the strangest places. The biggest surprise to me, and there’s almost a dark humor to it, was the material in my chapter about Native American religion. Most of the chapter is about the horrific discrimination and persecution of Native Americans on religious grounds. Obviously, we know there was persecution of Native Americans, but not so much specifically about this period after the Civil War, when the “good guys,” the reformers, had the idea that instead of exterminating the Indians, we should help them by forcibly Christianizing them. And that the best way to do that would be to take away their children and put them in schools that would immerse them in Christianity, as well as other parts of white culture. So religious institutions were basically assigned tribes. There are lists: The Methodists get these three tribes, the Baptists get these two. So this is chugging along, and there are a lot of horrible things about it, but all the white religious groups have bought into it until the Catholics start to get a disproportionate number of the assignments. And suddenly the Protestants think it’s a terrible idea to have religious groups involved in this. Because they don’t want the Catholics controlling the education of the Indians. And vice versa. There’s money involved, and there’s hysterical religious rhetoric, where they talk about how important it is for the Native Americans to have religious freedom—that is, religious freedom to pick which Christian denomination they’re going to be forced to convert to.

Eventually the whole policy fell apart because of the fight between Protestants and Catholics. It wasn’t as if there was some epiphany that maybe the Native Americans should have something to say about this, or maybe it violates our notions of religious freedom to be stomping out their religion. It wasn’t that. It was that the Protestants and Catholics could no longer agree on who would get to convert them.

Some passages in the book seem aimed at scrambling people’s conceptions, particularly evangelicals’. For instance, you suggest that conservative Christians worried that America is too secular should logically support increased immigration, and specifically illegal immigration, because immigrants tend to be more religious than the native-born.

I wanted to get people out of their grooves and thinking about these issues in more intellectually honest ways. Everything is such a team sport now. You’re given a set of ideas, and if you believe X, you also have to believe Y. And now that package includes your whole sense of history and what happened in the 19th century. There’s a progressive version and a conservative version of all of American history.

I try to overturn those. For instance, I say in the book that no group has done more to advance religious freedom than evangelical Christians. Which is, through modern eyes, a shocking thing to say, because of their political positions in the last 30 years. But it’s true. The nature of religious freedom in America drew in part from the evangelical understanding of the Bible. It was very important to them to establish a personal relationship with God, to use the modern lingo, and in the 18th-century context, that meant a diminishing of the authority of clergy, of religious institutions and of government.

Part of why I emphasize this, besides its being genuinely important and interesting, is that it challenges both left and right. It challenges modern evangelicals to rethink their approach to church and state and to religious pluralism. The debate I would love to see is not between a modern evangelical and a modern atheist, it’s between a modern evangelical and an 19th century evangelical.

But it also challenges the left, because there’s a tendency on the left, especially on the secular left, to think that evangelicals are to the core of their being anti-freedom, anti-justice and anti-tolerance, and that it’s almost baked into their religion. And that’s really not true. It’s not their self-image, either. And I guess I have a little bit of hope that if we could agree on that bit of history, it would create a platform for some common-ground discussion between the groups.

Have you found evangelical audiences receptive to that idea?

Well, I do find that when I’m talking to evangelical groups, the fact that I am so genuinely respectful and admiring of their role in this story, and their role in what I call America’s greatest invention, makes them much more open to then hearing my criticisms about their modern approach to Islam.

You present a very nuanced view of some issues important to the Christian right, such as the conflict between religious freedom and gay marriage.

That was the hardest issue to me, because I totally see both sides. Obviously, the gay marriage side is more straightforward. Same-sex marriage is a Constitutional right. You can’t use your religious freedom to violate other people’s rights. So in that sense, it’s very clear-cut. There’s some legitimacy to the analogy with interracial dating: Some people used to use biblical justification to ban interracial dating, and then we as a society said, no, you can’t do that anymore; that’s discriminatory, and it doesn’t really matter if you have a biblical justification for banning it. So by analogy, with same-sex marriage, you don’t get to have a religious justification to oppose what is now a constitutional right.

On the other hand, from spending a lot of time talking to and reading conservative evangelicals, and it could be true for conservative religious people of a wide variety, I can see that when you’ve spent your whole life being taught that something is a righteous position, and then relatively overnight, in the scheme of religious evolution, it goes from being a sign of piety to being a sign of bigotry, that’s a seismic cultural change. It’s very, very fast. What evangelicals’ real fear is, at this point, is not anymore that same-sex marriage is going to stay. They’ve given up on that. It’s that they won’t be able to have some safe spaces where they can continue to say what they’ve been taught their whole lives. That to me is a more legitimate concern. For instance, people would often ask in talking to me, should Christian colleges be allowed to still teach against same-sex marriage without losing their accreditation? That’s a live question. In the 1970s, the IRS took away the tax-exempt status of Bob Jones University because of its policy against interracial dating. They never enforced it—they won their court case, but then they backed off because of the political implications. But logically, the same thing absolutely could happen to Christian colleges on same-sex marriage. It wasn’t true before the Supreme Court’s Obergefell decision, because then it was a public policy matter, but now same-sex marriage is a constitutional right.

It connects for me to what is the hardest aspect of modern religious freedom jurisprudence to explain, or even to understand—what you might call the accommodation revolution. Starting around World War II, we went from viewing religious freedom primarily as the absence of persecution, or the absence of state-sanctioned discrimination against religions, to a much more expansive view, where the government and society as a whole said the government should bend over backwards to make accommodations for people’s religious lives, that we should try to minimize the instances where people are forced to choose between the law and their faith. It can be blue laws that pressure Jews or Seventh Day Adventists to work on Saturdays instead of Sundays. It can be exempting a nun who works in a hospital from involvement in an abortion, or allowing Quakers to be conscientious objectors and not serve in the military. Those are examples most of us would agree on. But when you think about it, the negative way of describing accommodations is that we’re exempting people from the law. We’re saying you don’t have to obey this law because of your religion. And it privileges religion, because in a lot of these cases, if you say, “I can’t work on Saturday because I want to visit my mom in the nursing home,” that is not a legally valid excuse. If you say, “I can’t work because that’s my Sabbath,” it is a legally valid excuse.

And on balance, I like this system. I think this is part of what gives Americans the American system of religious freedom, robustness and vitality that’s stronger than in the rest of the world. But it does create all sorts of dilemmas.

You also talk about the argument over contraception.

That was a fascinating case for all sorts of reasons. First, in the initial round the Obama administration really did mess it up, because they required religious organizations to arrange for contraception. But then Obama capitulated, almost entirely, and the administration came out with a second version that I looked at and thought, okay, they worked that out. But it was too good an issue for the right. So even though it had been fixed, it became this rallying cry where Trump was saying, “I am going to end the attacks on the Sisters of the Poor” and calling it an egregious attack on religious freedom. And you step back and ask, what is this egregious attack on religious freedom? Religious institutions, even religious organizations, don’t have to participate in this. If they don’t want to participate, they have to sign a form saying so and then it will be taken care of by someone else. That was the level of the burden. It was a teeny-tiny little burden, and this was the central religious freedom conflict of several years.

And it just shows how weaponized religious freedom as a concept has become. That’s certainly true. But I think it also shows that some of the religious freedom issues today are small relative to past history, because we’ve actually been pretty successful at working out the big ones. So we’re down to the harder cases, and that’s good news.

That’s why when I really tried to step back and say, “What are the big problems in religious freedom today?” I turned in a different direction and wrote about the attacks on Islam and the way we’re dealing with American Muslims.

You’ve said that the structure of religious freedom is fine today but you feel as if the foundations are soaked in gasoline.

We’ve had 10 years of a pervasive, persistent demonization of Muslims and their religion in the conservative, far-right social media world, talk radio world and Fox. I mean, the whole book is about attacks on religious groups, many worse than anything that’s happened to Muslims in America. But we’ve never had a presidential candidate make an attack on a single religion a central part of his campaign and win, and we’ve never had a media system like Fox News promote it so pervasively and for so long. Father Coughlin had his anti-Semitic radio show in the 1930s, but it went away eventually, and he was just one person. And Henry Ford had his Dearborn Independent, which was an incredibly anti-Semitic publication by a beloved American. It had hundreds of thousands of readers. So it’s not that media has not been a factor in promoting discrimination. But this is different. This isn’t a media outlet, this is an entire system of reinforcing attacks over 10 years or more, and I think that’s why you wind up with these horrifying opinion polls, like one in which only half of Republicans said they believe Islam should be legal in America. How do you get to that? You get to that because you’ve had a decade of these ideas being pushed. So that’s why I feel that we don’t know how bad it is, and we won’t unless, to continue the metaphor, there’s some kind of spark.

That’s a scary thought.

There is some good news: Even when President Trump announced the first travel ban, you had people flooding the airports and fighting against it, and you had Jonathan Greenblatt at the ADL saying, “If they establish a registry for Muslims, I will register as a Muslim.” And there were some court victories. The initial proposal got beaten back. You could look at the way that played out and see a real silver lining. It’s sick and sad that there is now a law on the books that was upheld by the Supreme Court, the origins of which were a blatant discriminatory move against Muslims. But the reality is, they did have to change it to make it seem less like that.

That’s one sign that the superstructure of laws and values and institutions that have developed to support religious freedom may be strong enough to withstand the next attacks.

One of the things that struck me as interesting about this narrative in the book is how little of it is really about Jews. They’re not really major players.

It surprised me a little bit. It turns out that relatively speaking, for the first 150 years, the level of persecution against Jews was minor compared to other religions. Maybe that’s a low bar. There was plenty of legalized anti-Semitism. In 1776, I think, nine of the 13 colonies banned Jews and Catholics from holding office, and 11 of the 13 banned Jews. So it’s not as if Jews had equal rights or anything close to them. But there were so few of them that they were not viewed as a threat, and so the level of hostility against Jews was more subdued compared to the hostility against Catholics.

That all changed after the massive wave of Jewish immigration at the turn of the 20th century, which changed the role of Jews in America and the attitude of America toward them. They were viewed more negatively. And then around World War II, things pivoted and tri-faith religious tolerance—among Jews, Catholics and Protestants—became an important American public value.

The Holocaust had the effect of cementing tri-faith religious tolerance because there was just more sympathy for Jews. But then subsequently, the Holocaust seems to have changed the Jewish approach to church-state issues as well. The American Jewish community, which to some degree had been partly sublimating Jewish demands in the service of multi-faith harmony—like, we want to try to build bridges with Catholics and Protestants, and that’s the primary goal, so if there are conflicts or things where we disagree, we’ll suppress those a little bit—after the war there was more of a sense that Jews could not afford to do that. That was the period when Jewish groups started to become really active in church-state cases, which they hadn’t been before then. They became strong advocates for separation of church and state and started to have conflicts with Catholics and Protestants on some of those issues.

There was a feeling that you had to pursue these things so as not to let down your relatives who died in the Holocaust?

Exactly. But there wasn’t much written about that element of it—at least that I could find. I bet there are probably people alive out there, maybe Moment readers, who know more about it.

It’s funny, though. I did an event for the book with a group of about 20 rabbis, and I kept wondering whether their questions would be about Jews or about religious freedom more generally. And almost none of the questions were about Jews, Judaism or the Jewish role in religious freedom. I thought that said something about how deeply the notions of religious freedom are ingrained in Judaism. It’s so pervasive that they just thought of religious freedom as a Jewish topic. It was obvious that even when the story of religious liberty wasn’t about Jews, it had a profound impact on Jews in America.

A theme in your book is that when previously persecuted groups show intolerance toward unfamiliar religions, they seem like hypocrites, but they get around it by saying the group in question isn’t really a religion, it’s something else.

Yes. In a way, the fact that people are forced to come up with that ridiculous construct is a sign that people have bought into the idea of religious freedom, really. That is the optimist’s way of looking at it, because it at least is verboten to say, “Yeah, that’s a religion, but it shouldn’t have freedom.” You can’t say that. So the way to keep the cognitive dissonance from making your head explode is to say it must not be a religion. We saw it over and over again, with Catholics, with Mormons, with Jehovah’s Witnesses, and now it’s happening with Muslims.

You point out that we are a nation of people descended from religious minorities.

That’s right. I actually did the math on this. The religious majority at the point of the founding was a combination of Congregationalists and Episcopalians. Those were the dominant groups in America. And those two groups together now represent 1.6 percent of the American population. Everyone else comes from a group that was persecuted at one point or another. I mean, everyone else was a religious minority, and most of them are descended from religious minorities that were persecuted, just because that was what happened.

Each one’s on the outs, and then eventually they’re inside, shooting outward.

Yes. It’s a sad recurring theme, the extent to which the folks that were persecuted then turn around and attack others. I guess that’s why we write history, to try to get people to maybe not do that.

Fascinating Interview and answers.

I am not coming from a vantage point of religion bashing…that is not my purpose or experience. I do, however, want to make a point of reference from my own unique experience. My encounter with the Living God ( He is One, Echad, the God of Israel, known through the Judeo/Christian Bible) gave me understanding that is not complicated, it is very simple. God is not about “religion”…that is truly a human construct. He is about Himself, as Creator of humans and all life. He reveals Himself through His creation (people, nature, animals, the heavens) and has made Himself known in a written record. He is the original author of Creation and the Word spoken and written. Everything recorded in His written record of the Bible explains who He is and what He wants us to know. All else is speculation. Humankind, in his/her fallen, less than perfect state, can distort to his/her advantage, and by his/her personal prejudices that recorded Word. And so he does. However, God’s purposes and written declarations will not ultimately be thwarted by human error. All that is contained in His Book is valid, whether we accept, reject or embrace it wholeheartedly. Deuteronomy 29:29: “The secret things belong to the Lord our God, but the things revealed belong to us and to our sons forever, that we may observe all the words of the law.” “Religious tolerance” can be fear-based, as well as religious bigotry. God is not about religion. He is about TRUTH in LOVE. As flawed human beings, we do not express this easily.

Religious freedom permits you to both believe that, and to state it without repercussion from the government. In earlier times, before the renaissance, using natural events were explained in terms of god, and god’s will. Today, we understand much more of nature and do not need to resort to god. Religion also provided early moral codes, rules of behavior. Today, we have laws to enforce behavior. In short, the reason for looking to religion for answers is declining.

Anti-Muslim sentiment is legitimately based on the orthodoxy of Islam, that it lacks or seems to lack any liberal/reform movements, and would gladly impose its religious laws on others; it does not conform at all to Western values, and is a threat to them. It is comparable to the opposition to Jehovah’s Witnesses and other cult-like religions. If you are going to talk about bigotry, you have to filter the differences between what is based on ignorance, fear, dislike, distaste, and what has much deeper and legitimate roots. When you have no limits on your values, you are formless, shapeless and lack integrity. Nothing is blanket. Opening the door to Gay Rights did NOT open the door to any kind of sexual rights. Opening the door to legal immigrants does NOT open the door to illegals and migrants. Inclusion does NOT mean including anybody and everybody no matter what. Grow up.