This post is part of the Israel Vision Project, a series of pieces about where a diverse set of Israelis envision the country going from here. For the rest of the project, click here.

Elsewhere, the bougainvillea bloomed brightly as Israelis went about their lives, including uniformed soldiers who were most at risk of losing them.

Protests continued to draw many and snarl traffic: At a Jerusalem junction a group of ultra-Orthodox waved placards calling for the end of the internet, which they fear will allow outside thinking to corrupt their way of life, and in big-city plazas and on highway overpasses throughout the country, angry, mostly secular demonstrators rallied for the return of the hostages and against the policies of the Israeli government.

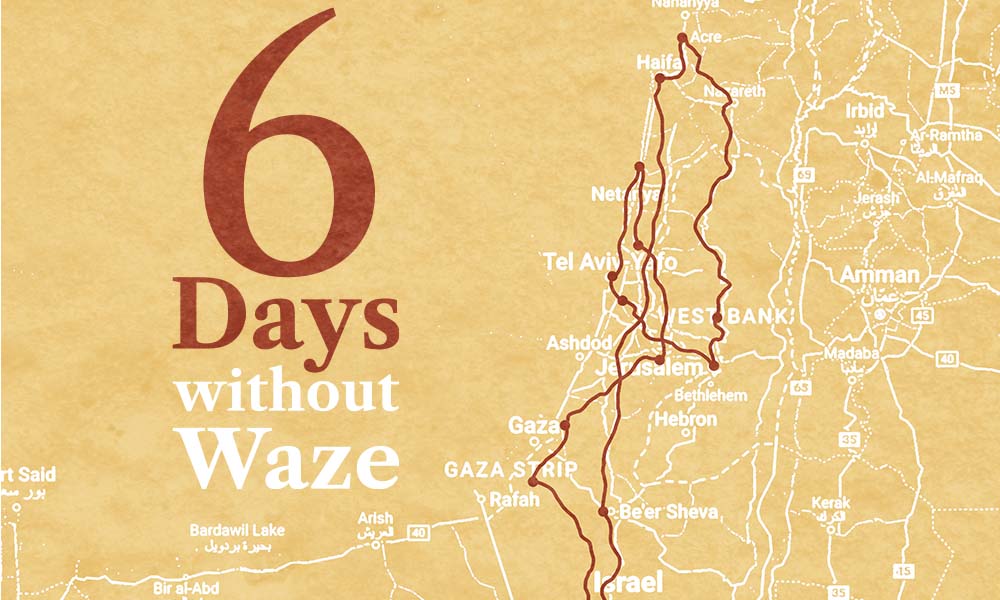

One usually reliable homegrown technology, however, wasn’t working. As if reflecting the loss of a metaphysical North Star, neither Waze nor Google Maps was functioning well. In many parts of the country, GPS identified our location as Beirut and mapped the trip from there, a recurring reminder that Hezbollah fighters were not far away, and the Israeli military was scrambling GPS to make it harder for their guided missiles to find their targets.

This left Moment Israel Editor Eetta Prince-Gibson and me without navigation as we drove from Jerusalem to the West Bank settlement of Ofra, from the Arab-Jewish cities of Akko and Haifa on the coast to Beer Sheva and Sde Boker in the Negev, from the Nova Music Festival site (now a moving memorial to those massacred there, as is the heap of burned-out and bullet-riddled cars a few miles away) to Tel Aviv/Yafo, Zichron Yaakov and Kfar Saba.

As if reflecting the loss of a metaphysical North Star, neither Israel’s Waze nor Google Maps was functioning well.

I had come to ask Israelis of all kinds to articulate their vision of Israel’s future, because, from afar, it was difficult to imagine what they were thinking in a time of tragedy and existential threat. I talked to 70 people in all, and themes gradually began to emerge. The first and most obvious was bottomless despair. A very high-ranking retired government leader whom I visited lamented privately that everything they had worked for was lost. A successful professional who had made aliyah decades ago questioned whether they would have done so now.

A parent who had spent their life building peace was struggling in the face of sending their children to war. A settler was losing hope for a normal life. A former diplomat had seen Israel through many ups and downs but never a “down” like this one. Yahya Sinwar’s brilliant plan had struck right into the souls of all of these Jewish Israelis and exploited their vulnerabilities, regardless of background, age, political or religious leanings.

Mostly I sensed fear, and a kind of vertigo. People were dizzy from not knowing what might come next or even what should.

Many people I spoke with believed the war was justified, but no one knew how it might end or what a plan for Gaza might look like. “The sheer level of open-endedness makes me the most nervous,” a usually composed and cerebral historian admitted. No one I spoke with, not even longtime supporters of Benjamin Netanyahu, had confidence that the Israeli government and military knew what they were doing. “Every morning, I wake up and pray that there is a plan,” a young reservist told me.

One night, at an event held under the stars at a winery in the Negev, I sat next to Rinat Galily, a survivor of Kibbutz Nirim.

Her quiet pain reverberated as she recounted her experience to me. Rinat and her husband had survived only because their neighbors, who were killed, owned a golf cart. The cart had distracted the terrorists, who had taken off in it and, as a result, missed their house. Galily is a marriage and family therapist, and after October 7, she helped other Kibbutz Nirim survivors find therapists, then sought help herself.

“Some of my clients and some of the therapists I was mentoring were slaughtered with their families,” she told me. In the beforetimes, she had led workshops in Gaza, and in 2022 she had traveled to the Polish border to train Ukrainian psychologists to work with internally displaced Ukrainians traumatized by Russian brutality.

She was stunned that she, her family and kibbutz-mates were now displaced and wrestling with similar trauma. Galily is troubled that government funds for therapy are drying up, because she has no idea when, or if, the pain will recede.

When I asked people to look forward, they often slipped into rewind mode to recount what and who was to blame.

The blame list is long and varied. Hamas. Iran. The current Israeli government. Bibi. Jews who have betrayed the Jewish vision. The United States. Biden. Internal divisions. Fragmented society. The ultra-Orthodox not serving in the army and not contributing to the economy. The settlements. The settlers. The Palestinian Authority. Mediocre political elites. Colonialism. The Ashkenazi-Mizrahi divide. Not enough Judaism. Too much Judaism. Segregated schools (ultra-Orthodox, Arab, secular, religious) that prevent integration. Too much capitalism. Not enough capitalism. A weak state. An all-too-powerful state. Social media and the awful discourse emboldened by it. Jihadists. Arrogance. Naivete. Evil.

Isaac Bentwich, CEO of Quris, an AI innovator; Meron Rapoport, A Land for All cofounder; Daniel Chamovitz, Ben-Gurion University president. (Photos by Nadine Epstein)

Yet in almost the next breath, everyone recognized the overarching need for internal unity. Many confided that the silver lining of October 7 was that it had brought Israelis together. Again and again, I heard that with the government paralyzed after the attack, Israelis of all backgrounds had stepped up to root out the terrorists and to aid the survivors. At least three secular Israelis told me this had led them to make a conscious decision to be less judgmental of the nation’s religious Jews.

The majority of people I spoke with told me that coming together as a nation is Israel’s first, and most daunting, task.

Although I’d love to be wrong, it quickly became clear to me that while people genuinely long for unity, the fences that divide them are so high that only a few people can see over them. When I spoke with Naomi Ragen, a novelist and Moment columnist whose views largely lean right, she told me that the brutality of Hamas had resolved the issues that had been tearing the Jewish people apart: Well-meaning people on the left “now saw the great error of their ways in trying to make peace with jihadists” and had come to share the views of the right, she said.

Ragen, who is Modern Orthodox, has only contempt for the concept of “land for peace,” which in her opinion misses the real reasons for the conflict, which are cultural and religious. In contrast, several people I met on the left were equally certain that all Israelis now clearly understood there was no choice but to embark on a path to establish a separate Palestinian state.

Israelis on both the left and right had inched toward the political center, but among the more partisan, there was no missing the different lessons drawn from the same events.

Yehuda Glick, an American-born Orthodox rabbi I spoke with in Jerusalem, is frustrated that the sense of unity was short-lived. “I was hoping that what we went through would cause people to be a little more aware of the diverse society we’re living in, but unfortunately, we see the same arguments that existed before, just with different pawns on the table,” said the rabbi, a former Likud member of the Knesset who leads the push for Jews to pray on Jerusalem’s Temple Mount.

“People refer to themselves as Messiahs and the other side as Satan, and vice versa. Everybody’s sure that they know exactly what’s right and the only problem is the other side.”

There were subjects almost everyone I spoke with did agree on. Despite calls from the far right for Israel to “go it alone,” including from some members of the current coalition government, most people believe that external intervention is a must.

Eyes are on the United States, Europe and the Sunni Arab world. Israelis on both the left and right see the Abraham Accords as a lifeline; they have set the stage for a new Middle East, the one where the economic engine of the “start-up nation” aligns with Sunni nations against Iran, and where people live good lives (fueled by cutting-edge technological advances, including those that make life in dry climes sustainable), generate wealth, and transcend the region’s troubled history.

Saudi Arabia is viewed as holding the keys to peace in the region, since it controls a high proportion of the wealth in the Arab world and, as guardian of the two holiest places in Islam, can confer legitimacy.

In fact, many of my interviewees spoke of Saudi Arabia as if it were Israel’s knight in shining armor. Those who don’t believe peace with Palestinians is possible hope the Saudis will help clean up the mess in Gaza and ensure Israel’s long-term future without the creation of a Palestinian state.

Those who want a cease-fire now, or not too far in the future, hope the Saudis will help stabilize Gaza in the short term, then stand at Israel’s side as the process of Palestinian statehood unfolds. I heard completely different versions of what Saudi Arabia wants, depending on where people stood politically. Some argued a Palestinian state or at least a path toward it was a requirement for the Saudis, while others said the Saudis couldn’t give a fig about a Palestinian state or about the Palestinians themselves. One person told me that Saudi Arabia would lose respect for Israel if it folded to pressure to end the war before Hamas was vanquished. There was much M.B.S. (Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman) mind reading, and a propensity to project political views onto Saudi Arabia’s white sands.

The geopolitical shift brought about by the Abraham Accords is very real. I experienced it firsthand. Since October 7, many airlines have suspended service in and out of Israel, and in April, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan announced that one of the biggest carriers, Turkish Airlines, would stop flying into Ben-Gurion. So there weren’t many flights to choose from when United Airlines canceled my return flight to Washington. I reticketed via Dubai on Dubai Airlines, which is owned by The Emirates Group, which in turn is owned by the Dubai government.

I could do this because The Emirates Group has not pulled out of Israel despite the Israel-Hamas war and the international backlash against Israel. The plane was filled to capacity with Israelis, some in religious garb, who, when we arrived, blended into the multitudes at the Dubai International Airport.

It’s far easier for Israelis to pin their hopes on geopolitical realignment in the Middle East than on their own government.

Criticism of Israel’s longest-serving prime minister came from more directions than I had expected. I didn’t penetrate far into the insular ultra-Orthodox world or into cities in Israel’s periphery where many of the 25 to 32 percent of Israelis who still support Bibi are said to reside, but I did talk to a range of people on the right.

Naomi Ragen, for one, said Bibi had lost her vote since October 7 had occurred on his watch. Ran Baratz, founding editor of the Hebrew-language conservative news site Mida and a former director of communications for Netanyahu, said he was proud of the prime minister’s many accomplishments but questioned whether he had the Churchillian qualities required to lead the nation through a war. Even the Israelis I spoke with who lived in West Bank settlements thought Netanyahu’s brand of politics had become too toxic. One settler said she would still support Netanyahu, at least for now—not because she trusts him (she doesn’t) but because for the time being she thinks his personal goals are aligned with those of the country, and that makes her feel safe.

Not that it matters. Except for wishful thinkers on the left, no one really thinks there will be an election until after the war, whenever that is. The ultra-Orthodox parties (which represent 13 percent of the population and have the highest voter turnout) have no other real allies and are unlikely to abandon Netanyahu, who remains their best hope of keeping their young men out of the army.

And when the time comes, no one thinks Netanyahu will go quietly; realists expect many grueling election cycles before any new leaders emerge. Wherever I went, I heard disdain for Israel’s political parties and fear for its political system. I also listened to divergent interpretations of what democracy is and should be. Critics of the government’s recent efforts to curtail the powers of Israel’s Supreme Court believe that the country’s democracy is heading down a slippery slope where minority rights will be curtailed and the party in control of the Knesset will govern unchecked. Supporters of the overhaul blame decades of judicial activism by the Court for undermining Israel’s democracy by wresting power from both the legislative and executive branches.

With politics frozen for the foreseeable future, and ultra-Orthodox and religious Zionist parties holding the reins of power, many of those I interviewed, from left to center right, are putting their faith in an ecosystem of social movements, NGOs and civic initiatives. Organized through social media, listservs, WhatsApp and the like, they may fade away once the political system becomes less stagnant, but for now, they are a national obsession. As the leader of one explained, movements “are the one thing that can provide the public with different options and different political ideas they can choose from.” Best known is the massive anti-judicial reform protest that mobilized the left—and some of the center—before October 7. This movement was made up of groups such as Brothers in Arms (reservists and former military), Black Flags (led by physicist Shikma Bressler and her siblings) and the Kaplan groups, named for the Tel Aviv street where demonstrations in that city are held.

Post-October 7, the anti-judicial reform movement metamorphosed to call for the release of the hostages, and new groups emerged to lead it. The largest is the Hostage and Missing Families Forum, which holds demonstrations every Saturday night outside the Tel Aviv Museum of Art (in what is now popularly referred to as Hostage Square) and coordinates international efforts to free the hostages. Another group meets earlier on Saturday outside Tel Aviv’s Habima Theater to demonstrate on behalf of the hostages, but more broadly against the government. And lest you think only the left and center are out on the streets, the right-leaning Tikvah Forum also organizes protests on behalf of families of hostages that support Netanyahu’s policies.

With left and center parties largely sidelined since 2009, various initiatives have filled the vacuum in that part of the political spectrum. One is Blue White Future, which was founded that year to grow support for a two-state solution, and later threw its weight behind the judicial reform protests. Its cofounder, Orni Petruschka, is a fighter pilot turned engineer who made his fortune as a high-tech entrepreneur in the alternative energy field. In order to preserve Israel as a Jewish and democratic state, he told me, “it’s necessary to have two states, so that Israel is Jewish, with holidays that stem from the roots of the Jewish people that are celebrated, but not with a rabbinate that has control over anyone.” Religion, Petruschka said, “should be a matter of choice.” He envisions a demilitarized Palestinian state in conjunction with Israel being accepted within the region.

I met Sally Abed, a young Palestinian Israeli, at a café in downtown Haifa. She’s one of the leaders of Standing Together, a small movement founded in 2015 of Jewish and Palestinian Israelis who want to change how the country’s citizens talk and think about peace. “Very few people are actually willing or able to imagine that kind of future right now,” she told me. “It’s our job as a grassroots movement to create the political imagination so that more people will see it, to make the idea of safety and security and a prosperous future accessible. Then we can work on the details.” Abed, who was born in the western Galilee Arab village of Mi’ilya, won a seat on the Haifa City Council last year.

The details could start with two states, a confederation or one state, but in the long run, Standing Together’s vision is not for a Jewish state but for Israel’s nationalities living side by side in freedom and safety. “We are just so consumed with surviving and fighting for a right to not die that we don’t dare to dream about lives that are prosperous and joyful,” she said. “We live in one of the most beautiful spots on earth. I want to be happy. I want to be safe economically and socially. I want to be safe personally on the streets. And I want everyone around me to prosper in a country that has a state and a government that serves us, that exists to serve its people and their safety in the deepest sense. When we say safety, it’s gotten reduced to national security. Right now, the vast majority of Jewish Israelis believe we have to control five million people and be wary of 20 percent of our own citizens to be safe. I want us to be past that. I see that not just as a Palestinian. I see that as an Israeli citizen.”

No one completely ruled out a Palestinian state in the future, but no one thought it was closer than many years, even generations, away.

In Yafo, I talked with Meron Rapoport, one of the founders of A Land for All, a group on the left that advocates for a confederation of two states, one Jewish, one Palestinian. “You can call it a confederation, or you can call it a union that allows for the things that are shared to be shared, and the things that should be run separately to be separate,” he said. “It sounds a little bit abstract, but take the example of the European Union, or the resolution of other conflicts since World War II such as the one in Northern Ireland. It’s not all roses, but it works. People don’t forget the past so fast, but sharing power is the best guarantee for peace, stability and eventual reconciliation.”

I visited the West Bank settlement of Ofra. It’s less than 20 miles from Jerusalem via a road that intentionally bypasses Palestinian communities, but they are long miles through barren hills spotted with olive groves and, always, a security apparatus that is both visible and invisible. There I met Netzach Brodt, an international tax lawyer, and his family. He told me about an initiative that inspires him called The Fourth Quarter.

Founded by historian Yoav Heller in 2022, its mission is to build a broad alliance of Israelis, focus on forward-thinking solutions rather than victories, and foster a politics of humility. “There’s a feeling that we have reached a critical time in the history of Israel and the situation is fragile,” Brodt said. Twice in the history of the Jewish people, following the reigns of King Solomon and the Hasmonean Queen Shlomtzion, Jewish kingdoms collapsed as they entered the fourth quarter of the first century of their existence, falling into civil wars after having lost touch with their foundational values. Brodt said people from all the “name tags” of Israel—including the ultra-Orthodox and the secular, Jews and Arabs—have joined The Fourth Quarter; they believe that 70 percent of the population agrees on 70 percent of the issues and that these areas of broad agreement should be “laid out as the fundamental infrastructure for the next generation to be successful.”

Brodt has been serving in the reserves since October 7 and told me he wished Israeli society could be modeled on the integrated and supportive culture of reserve units.

Not all his neighbors in Ofra, a long-established and relatively close-in settlement, hold such conciliatory views. One analyst told me that the settlements and their councils, which lead the expansion into the West Bank, themselves are social movements. These movements include extremist, violent settler groups such as the Hilltop Youth and follow the increasingly popular ideology of Meir Kahane, who believed that Palestinians are “raping the Holy Land” and must be expelled. The movements on the far right don’t waste any time giving lip service to consensus and democracy; their mission is to hold onto land they believe belongs to the Jewish people and to safeguard Jewish identity as they see it. These views are echoed to varying degrees by more mainstream right-wing advocacy and watchdog NGOs, which have become as numerous as human rights groups on the left.

Throughout my journey, I listened to wildly different thoughts about the Israeli-Palestinian future. I didn’t personally meet anyone who explicitly called for one state only—either for Palestinians or for Jews—though obviously there are such people.

And no one completely ruled out a Palestinian state in the future, but conversely, no one thought it was closer than many years, even generations, away, given the radicalization of the West Bank and Gaza. Ran Baratz, Netanyahu’s former director of communications, shared what has become the official position of the Likud Party: First, a Palestinian state won’t happen until “the Palestinians reach the point that they want to have their own state living side by side in peace with Israel.” Second, a Palestinian state is not relevant to the Israeli-Sunni alliance needed to contain Iran.

There was one last thing pretty much everyone was betting on: Israel’s unique ability to continue to generate growth far beyond its size. This is itself a form of Zionism, explained Isaac Bentwich, whom I met in the hip Tel Aviv quarters of his company Quris, an artificial intelligence innovator that seeks to transform the drug development process. Once “we manage to collectively pass through these dire straits,” said Bentwich, “the business synergies between us and the surrounding countries will change the world.” I heard talk that academic boycotts and frightened investors could inflict damage, and already were doing so to some extent, but there was optimism that Israel would power through. Dan Blumberg, the head of the Israeli Space Program, predicted that in five years Israel would be generating more technology than ever, including more agile, streamlined and affordable satellites. The challenge, he told me, is an internal one: The ultra-Orthodox need to learn math and English. “Torah learning has never stopped people from working, from going into industry and from going to new places of work,” he said, noting that religious scholars such as Rashi often held jobs.

One morning in the Negev, the desert region that Israel’s founding prime minister David Ben-Gurion hoped would supercharge Israel’s growth, I had breakfast with Daniel Chamovitz, the president of Ben-Gurion University and a plant scientist. We met in a crowded hotel restaurant in Sde Boker, just yards from the modest kibbutz home to which Ben-Gurion and his wife retired in 1970. Given the university’s location in the south, a high proportion of its students were killed or taken hostage on October 7, and Chamovitz shared that he had made 37 shiva calls since then.

Overall, he said, the country’s millennials and Gen Z are bearing the brunt of the war with Hamas in terms of numbers captured, injured and killed. “After what happened on October 7, the younger generation, ages 18 to 35, who we thought were superficial and criticized as the TikTok generation, have proven themselves to be the strongest generation ever in the history of Israel,” he told me. “And that’s saying a lot. They’re fighting the hardest war, they’re dealing with greater losses than ever before, and they’ve had to leave jobs where they were making very good money. What brings me hope is that this generation now has to take on the mantle of leadership.

My generation, the generation that came of age after 1973, has failed.”

Not surprisingly, young Israelis I spoke with wholeheartedly agree, whether they are left, right or somewhere in between. Some said that they are finding ways to peek over the walls that separate Israelis and, although they have as many policy disagreements as their elders, are more willing, and even excited, to work together. One 29-year-old who described himself as a secular “center-left Zionist” has been extending his hand to Orthodox and ultra-Orthodox Jews in his age group. “A lot of other young Israelis want peace, but we’re in the minority; most young Israelis are more right-wing and right-leaning and more conservative and religious,” said Nadav Salzberger, a leader of Change Generation. That group has developed a detailed plan for a revamped government, including expanding the Knesset and creating a separate high court to review Israel’s Basic Laws. But its main purpose is to connect young people—using texts, social media and video talks that employ humor and outrage—from across the political and religious spectrum. The goal, said Salzberger, is to make them realize that the current government doesn’t have a realistic vision for Israel and to move them a step to the left. “Some [ultra-Orthodox] came into our tents during the protests,” he told me, “and although we didn’t see eye to eye, there was a lot of exchange going on.”

Salzberger is convinced that there are young ultra-Orthodox who are searching for ways to be part of the larger society, or who are at least curious. “They are going through processes that are hidden from our eyes,” he said. As his grandfather, the writer Amos Oz, once told him, “Unlike books, people can change…people can surprise those around them and even themselves.”

Despite the despair, wishful thinking and the occasional delusion, I came away from Israel hopeful. Without Waze (one of the great technologies invented in Israel), I managed to find my way around. I’m betting that Israelis will find their way too.