It’s Friday afternoon kiddush time, pre-October 7, at Halper’s Books on Allenby Street, the weekly pre-Shabbat get-together of friends, customers and any stranger who wanders in. Longtime owner Yosef Halper describes the gathering as South Tel Aviv’s “Parliament” for the city’s English-speaking diaspora.

“We’ve left our families,” says Halper, the 63-year-old New Jersey-born master of ceremonies, as a bunch of regulars swirl around him and his iconic store. “We’ve come here and made our own families. It brings us together.”

Among this afternoon’s more-than-a-minyan crowd are Matthew Morgenstern, professor of Hebrew language at Tel Aviv University (“There aren’t that many great English bookshops left in Israel”) and Hananya Goodman, director of libraries at Shamoon College of Engineering in Ashdod, who made aliyah from Wisconsin in 1983 and now practically counts as a kiddush cohost. (“I love book people…I just decided to plant myself here and bring food, alcohol, cheese.”)

Amid the lox, herring, Jack Daniels, Schweppes and Hellmann’s mayonnaise set on an old wooden table, new regulars include Tal Baron, a 31-year-old international chess grandmaster whose girlfriend, a Missouri native, told him about the shelf of chess books at the store. (They’ve been coming back ever since—he bought six books and donated them to a 100-year-old Tel Aviv chess club.) Another newbie is Oren Kessler, author of the recently published Palestine 1936. (“This is a fairly politics-free zone,” he says, nursing a drink, “but not by design. There’s no rule about it. People just tend to talk books and bullshit, and joke around.”) In fact, you never know who might pop into the 32-year-old used bookstore, 60,000 volumes strong and located down an alley that attracts both browsers and—this is not chi-chi North Tel Aviv—the occasional late-night urinator.

Egyptian Ambassador to Israel Khaled Azmi came by one evening and signed Halper’s guestbook: “To Yosef, Thank you so much for the real treasure and wonderful oasis of knowledge you kindly provide. It was a real pleasure to know you.” The actress Amber Heard stopped by shortly after her Johnny Depp trial, just the latest in a line of celebrity drop-ins who’ve happily graced Halper’s guestbook over the years. (“To Yosef, all of my gratitude and respect. What a gem to find such a beautiful place. Thank you, all my best, Amber Heard, fellow misfit and troublemaker.”)

On an earlier page filmmaker Joel Coen turns up (“Great bookshop!”) and novelists Tova Reich (“Wonderful shop!”), Nicole Krauss (“Looking forward to getting lost and being found here”), Joshua Cohen (“In admiration for the world you have created in your bookstore”) and Jonathan Safran Foer (“My favorite used bookstore in the world”). Nonfiction sign-ins include author and former Israeli Ambassador to the U.S. Michael Oren (“To Yossi, love of Israel, love of books, and love of New Jersey, not necessarily in that order. What more can two humans have in common!”)

The new wrinkle at the old store, however, is that the boss is now a kind of celebrity too. Halper’s first book, The Bibliomaniacs: Tales from a Tel Aviv Bookseller, brings together short stories drawn from his more than three decades of kibitzing with customers. It excited his wide circle of literary and political friends, as well as Israeli critics, who praised his down-to-earth style, his droll streetwise humor and his dead-on grasp of the nuances of Israeli personalities and culture. The bookseller, it turns out, is a rather accomplished storyteller.

“It’s a great book, very well written, very Jewish, very fluent, very colorful, very cinematic,” says Eran Shar, a filmmaker and 20-year customer, hanging out at the kiddush. Shar first came to Halper’s because it was “the only place to find English film books. He has a section for everything.”

“We make war as if there’s no kiddush, and we make the kiddush as if there’s no war.”

“The book’s fantastic!” chimes in Kessler. “I really enjoyed it. It’s so Yosef.” Kessler came to Israel in 2006 right after college, wrote for The Jerusalem Post and Haaretz and is now a Halper’s regular. “Once you know Yosef, you see how reflective of his personality the book is. It’s written the way he talks.”

Indeed, the book is a rambling, funny, occasionally poignant grab bag of experiences, laced with Yiddishkeit that only an American used-bookseller in Israel could collect, and only an American oleh (immigrant) could retell with the sardonic lilt of a Jersey wise guy.

Consider some of the characters: The book-thief professor who admits, “I would kill for books.” Julian the Wild Man, who becomes “the first person ever to openly light up a joint at a table inside an ultra-Orthodox Bnei Brak wedding hall.” The Arab Muslim pair of textile workers, casual friends of the bookstore proprietor, whose reaction to a book of pornography almost causes an explosion. The 80-year-old retired music teacher and horndog from Cleveland, “like a hormonal preteen let loose in a strange city with limitless cash,” who cannot protect his money from hookers or keep his eyes off a shayna tuchas he encounters in Halper’s aisles.

One reviewer wrote that the only false sentence in the book was the one that claims it is fiction. Halper acknowledges that some of the stories, such as “How I Became a Bookseller,” keep close to his factual past, but explains that he embellished a lot in other tales, changing names, massaging some facts and, like any fiction writer, protecting the guilty.

He’s in no danger of running out of material. As Halper talks, anecdotes spill out. The time the mailing address of an order for a book on Danish royalty turned out to be Buckingham Palace. He checked—it was for real. (“I stuck a whole bunch of my store magnets inside, hoping the Queen would stick one on her refrigerator.”) The books in German he almost rejected from a young man wanting to dump his great-uncle’s library until the man mentioned that his great-uncle had studied with a famous Swiss psychiatrist (the one book signed by Carl Jung brought Halper $2,300). The letters from Ben-Gurion he found inside a box of donations. The $900 Waterford pen left in another box by a wealthy donor.

The backstory of Halper’s aliyah to Israel and rise to becoming a Tel Aviv institution includes some unusual twists and turns, but it’s also a familiar oleh tale—attraction, uncertainty, commitment, evolution—the tale of becoming an Israeli while remaining an American.

By the time he was a teenager, James Charles Halper already felt Israel seeping into his bones and soul—a 1968 family trip and weeks in 1976 at the Ben Shemen Youth Village among his early experiences. In 1983, after graduating from Yeshiva University, he made aliyah, served in the IDF’s prestigious Nahal Brigade (where he met his Iranian-Israeli wife) and started a family that now boasts three daughters and a son.

In 1991, with the lease on his Jerusalem apartment expiring, he returned to the refurbished basement of his parents’ home in Springfield, New Jersey, with his wife and two babies as the young couple contemplated their future. In his mind, however, remained the idea of starting a bookstore in Israel, a thought first triggered by a “For Sale” sign on Sefer ve Sefel, the old used-bookstore down a Jerusalem alley that Halper considered a kind of paradise on earth.

After a short period hawking books on Sixth Avenue in New York City—at the well-known Greenwich Village sidewalk mall near the basketball courts south of Eighth Street—and with the Gulf War coming, Halper and his wife made their decision. They belonged in Israel. They moved back in 1991 to the city of Petah Tikva near Tel Aviv. “I believed in this country,” Halper says, and at first he became seriously observant.

True to his dream, he rented a space down an alley on Tel Aviv’s grubby Allenby Street, then full of the seedy resonance he associated with Manhattan’s now departed used-bookstore strips on lower Broadway and Fourth Avenue. (Allenby at the time featured a fair number of prostitutes across the street by the Great Synagogue, a porno theater, and street people galore.) After a struggle to reclaim the many books he’d mailed from the United States—a tale told in “How I Became a Bookseller”—Halper’s Books was born in November 1991.

Thirty-two years later, Halper’s 33- year-old son, Yehuda, helps out at the store on most days, picking up donations in his van and trying to create order in the back storerooms crammed with yet more books, mostly for sale through AbeBooks, the online used-book clearing house.

“It’s a mess, a mess,” says Yehuda, working hard even as his father glad-hands visitors to the kiddush. “But I love it. I like the mess.”

Will he eventually take over? His mother and three sisters rarely come to the store, though some of his mom’s paintings hang over the front desk. “I’m not like my dad,” says Yehuda. “He is more of a book person. He’s literary. I read, but not the same way. But I’ll help him as long as he needs me. Hopefully he’s going to be here as long as he can.”

On the morning of Saturday, October 7, Halper woke up very early, around 6:30 a.m., without an alarm. Normally on Shabbat he disconnects from the world. He wasn’t sure if the distant booms he heard from the direction of Ashdod and Ashkelon were the reason. He had a flight to Newark at midnight and much to do. Doctors had diagnosed his mother in Boca Raton with an irregular heartbeat, and he was headed there to help. He also planned to do some bookstore readings of The Biblomaniacs in the United States. He turned on the radio.

As the news got progressively worse, Halper understood that he might not be leaving. Then Yehuda called, a rarity on Shabbat. He’d been staying with his wife’s ultra-Orthodox family in a Haredi neighborhood in Jerusalem. Yehuda was phoning from his car. He and most of his friends and cousins had been called up as reservists—he needed to grab his duffel bag and head to his infantry unit at the Lebanese border. Like his father, Yehuda served in the Nahal Brigade. Halper canceled his plane ticket and found himself in and out of his bomb shelter all day.

By late Saturday, as the scale of the Hamas attack became clear, others checked in. Halper’s friend Hananya, on the front line of the rocket barrages in Ashdod in his upper-level apartment, spent much of Saturday in his stairwell before racing to close friends near his daughter’s home in Jerusalem.

Halper’s Friday kiddush crew. (Photo credit: Courtesy of Mathew Morgenstern)

The following days brought more difficult news. October 7 seemed to touch everyone. Kessler notified Halper and friends that Tomer Shoham, the son of his cousin Michal and the commander of an elite spearhead Nahal platoon—soldiers who often go into dangerous situations first—had been killed battling terrorists at Kibbutz Kerem Shalom near Gaza. A friend of Halper’s youngest daughter had been shot in the stomach and killed, along with hundreds of others, at the music festival.

Like many store owners in the aftermath of October 7, Halper kept his shop closed, staying glued to the TV, radio and internet. A part-time assistant went to the store two days later but left after two hours, telling Halper there weren’t “even flies buzzing” on Allenby.

Halper returned to the store on Wednesday, October 10. He reopened for a full day. “I’d had it with 18-hour-straight news binges in front of the television each day,” he says. “I would flip Hamas the bird, and open as an act of defiance—feigned normalcy, with a blitzed London in mind.”

Business that first Wednesday proved slow. Most stores on Allenby remained shuttered. But it gave Halper a good feeling that the hummus guy in the front of the building had returned, along with the taxi drivers, who were sitting around arguing about how much blame Netanyahu bore for the disaster. Then the Persian dress shop reopened. And the watchmaker.

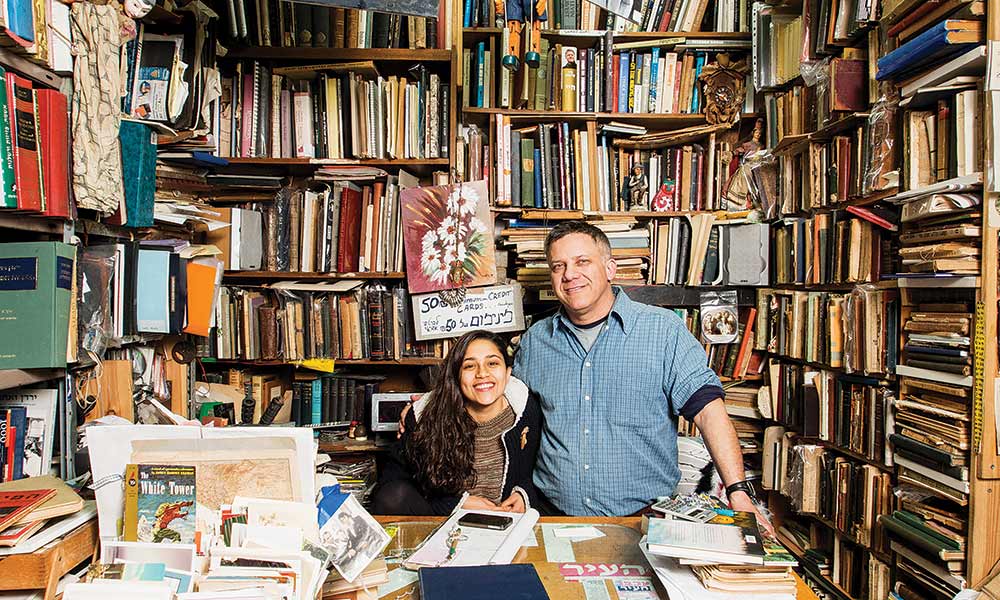

Halper and his son Yehuda. (Photo credit: Courtesy of Yosef Halper)

Pedestrians started appearing on Thursday, but the sirens two or three times a day, the “massive wall-shaking booms of the Iron Dome missiles knocking Hamas missiles out of the sky,” and the runs to the “dusty, musty, claustrophobic” bomb shelter in his building’s basement hardly made for normal days. “By 4:30 in the afternoon,” Halper says, “it’s like a ghost town.” He decided not to go to the bomb shelter anymore, to stay in the stairwell during siren times.

A week later, Halper was back to a third or half of his normal sales. On the first two Fridays after October 7, he decided to revive the kiddush. “We make war as if there’s no kiddush,” he says, “and we make the kiddush as if there’s no war.” A few regulars, like Professor Morgenstern and Hananya, came. “We polished off a bottle of Chivas Regal that I found in an old apartment,” one of the many, he says, where he goes to pick up used books. “Great stuff.”

Some new folks showed up too. One was a “stand-up British army veteran who used to be married to an Israeli.”

“He writes and edits,” says Halper, “but he’s evasive when asked his family name. We already have him slotted as a deeply embedded MI6 plant in Israel. A good lad, though, and a key addition to our group.”

By mid-December, Halper’s Books’ identity as a “politics-free zone” had ended. “Almost everybody in Israel has served in the army,” Halper explains, “which makes everybody an expert on defense issues, second-guessing the generals and politicians on both strategic and tactical points. Conversations in the store reflect this as well now. Even if people are much more civil to each other than before.”

Other changes have come to post-October 7 South Tel Aviv. Halper’s landlord “very considerately” gave him a break on his rent since he remains at 50 to 75 percent of pre-war sales, and the landlords of many retail establishments on Allenby have been giving similar discounts to their tenants. Halper realizes that “fear of empty real estate” may be part of the motivation, but says there’s also a “sincere attitude that ‘We’re all in this mess together’—that’s one of the greatest things about the Israeli national character.”

One clear downside of the post-October 7 period is that most of the usual tourists, as well as many English-speaking expatriates and dual citizens, have fled Israel. On the other hand, Halper points out, the usual traffic jams and parking problems in the neighborhood are largely gone. And thousands of Israelis from South Israel and near the Lebanese border, forced to abandon their homes, have moved to Tel Aviv. “There are tens of thousands of internal refugees from the north and south of Israel ensconced in all of Tel Aviv’s hotels,” says Halper. “I’m meeting quite a few new customers from this source. They’ve got a lot of time on their hands, if not ready cash. But I give them discounts. There are also many soldiers on leave who visit Allenby with their families. You see hundreds of young men and women in civilian clothes lugging their assault rifles along with baby carriages. Quite a sight!”

Halper remains hopeful about Israel’s future. The whole country, he says, has come together in support of the soldiers, and against what all view as an existential threat. “Had Hamas added a few thousand more fighters, they’d have been able to take the entire Negev, Ashkelon, and possibly the airbase near Beersheva and the nuclear reactor in Dimona,” he says. “Had Hezbollah jumped in at the same time, I don’t think that Israel would have survived.”

Halper has noticed less polarization over the past two months. “From the left, there’s less push for territorial compromise with the Palestinians,” Halper notes. “The kibbutzim that were attacked were amongst the most far-left in Israel. Firm peaceniks.” On the other side of the spectrum, “Bibi’s push for judicial reform is finished,” he asserts. “In the words of one of his closest allies, Yoav Kisch, the minister of education, ‘For the past nine months we’ve been engaged in shtuyot (nonsense).’ It was nonsense that was tearing the country apart.” He later jokes, “The only judicial reform that Bibi can now take credit for is our blowing-up of the Supreme Court building in Gaza.”

While Halper sees that the war has shaken “people out of their beloved political positions,” he knows there may be a return to mutual acrimony and recriminations after the war. Maybe, he hopes, “the shock of what happened will bring new leadership to the fore, cooler, more practical heads, perhaps from the ranks of our selfless young soldiers.”

Halper remains optimistic that his store “can and will continue as before.” He still hopes to come to the United States once the Gaza war ends to see his mother, who’s doing better, and perhaps give some readings from The Bibliomaniacs. But if “Hezbollah turns it into a two-front war,” he says, all bets are off.

What is the exact address of the Halper’s store? Thanks.