Robert Siegel interviews Susan Neiman

Monuments, holidays and patriotic anthems typically celebrate love of country and pride in national history, but since the end of World War II, Berlin has been an exception. When its eastern side was the capital of the communist German Democratic Republic, one monument lionized the Soviet Red Army, whose advance led many Germans to flee west. Today a Holocaust memorial stands in the center of the city, and “stumbling stones,” blocks embedded in the pavement, document the names and dates of residents who were deported during the Third Reich.

Germans have devoted so much attention to working through their Nazi past that their capital city has become an attractive home to some Jews in recent years. Among them is the philosopher Susan Neiman. She grew up in Atlanta during the civil rights movement and later earned a Ph.D. at Harvard University. Neiman is director of the Einstein Forum, a think tank in Berlin, where she has spent much of her adult life. When she has not been writing about Immanuel Kant and the enduring virtues of the Enlightenment, she’s written about being Jewish in Berlin. Neiman’s new book, Learning From the Germans: Race and the Memory of Evil, concerns that German process of “working off” the past and, by way of comparison, how the United States might do the same with its legacy of slavery and contemporary racism.

When we compare two historical phenomena, in this case the Nazi Holocaust and American slavery and racism, it’s not hard to find differences—in duration and consequences and how central each was to the development of the national economy. What’s at the core of both national experiences that invites comparison?

What I think is common are wounds of a war, wounds that have affected national narratives, national self-understanding and the ways in which ordinary people treat each other down to this day. What the Germans have done—with difficulty, it took them a long time to do it—is face up to what horrible crimes were done in their name, and they’ve become a better country for it.

You spent a year in Mississippi studying how some people there are trying to memorialize the victims of segregationist violence—Emmett Till and the murdered civil rights workers Michael Schwerner, Andrew Goodman and James Chaney. What specific lessons can Americans take from the Germans about creating a new national narrative?

One of the people I interviewed in the South was Bryan Stevenson, who’s most famous for his work on the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, the memorial to the victims of lynching that opened in Montgomery, Alabama in 2018. He said that his work on that memorial was very much influenced by what he saw in Germany. Prior to that, he had been working against the death penalty, and he was impressed by the ways in which Germans thought about the death penalty and how it was used and abused during the Nazi years.

He points out that in the South, you can hardly go a couple of miles without seeing some monument to the Confederacy. It’s very much part of the landscape. He argues that, first of all, Americans need to confront the fact that real acts of terror were committed, the memories of which we would prefer to suppress or record under the very silly and trivializing name of the Jim Crow period, when actually it was a systematic regime of racial terror in many parts of the country, not just the South. I should emphasize that I went to Mississippi not because I think there is no racism anywhere else, but because the Deep South does talk about its history. Everything is much more in the open there. So it’s a magnifying glass for looking at the rest of the country.

It was an extreme place. Hodding Carter III, the Mississippian journalist who used to work in the Carter administration, likes to say, “I lived in a police state.” There was an official state organ that surveilled people and investigated anyone who was trying to change the Jim Crow laws. We didn’t have that in New York when I was growing up.

Well, that’s correct, but by looking at the extremes we can say something about the way things are in the rest of the country.

I was surprised by how impressed you were with East Germany’s early response to the Nazi era as opposed to West Germany’s. The West Germans may have been in a state of denial for a generation, but they paid reparations both to individual Jews and to the State of Israel. On the other hand, I remember in 1983 being in Dresden in East Germany at the Museum of the History of the War to Liberate the German People from Fascism—a construction that, to me, sounded as if the Germans were victims of fascism rather than its enthusiasts. I recall searching in vain for the word Jew in that museum. Also, politicians in the West were at least accountable to voters. Those actions by East Germany, I always thought of as being less popularly authentic.

I know that this is going to be the most controversial chapter in the book. The leaders of East Germany, all of whom had been in exile during the Nazi period, were Germans, not Soviet Russians. Quite a few were Jewish, and they had been the first victims of the Nazis. The first people that the Nazis attacked were the communists; then they went for the social democrats and then the Jews. And I think it is very important to remember that when we think about the devastation that Nazis caused all over Europe, the Jews were not the only victims.

In the West, acknowledgment of Nazi crimes came much more slowly. West German President Richard Von Weizsäcker used the words “day of liberation” about the end of World War II for the first time in 1985, on its 40th anniversary. Before that it was called the Day of Defeat or the Day of Unconditional Surrender. It was a day to be mourned in West Germany and not even discussed. Many historians have studied the ways in which ex-Nazis continued to staff the government. Konrad Adenauer, the first postwar chancellor of West Germany, was not a Nazi, but his top staffer had contributed to writing the Nuremberg Laws. Meanwhile, the courts and the German version of the FBI were full of ex-Nazis. There was a silent bargain made in the 1950s and 1960s that “Okay, we will pay reparations because we would like to be accepted back into the Western community of civilized nations, but in return we won’t say anything about the war.” On the contrary, in the East, I interviewed a lot of people, looked at a lot of old records and there was a genuine contrition from the people in power, which you simply did not get in the West.

Let me agree with you that this will be the most controversial chapter in the book! To move back to the US, you don’t sound very impressed with the West German reparations. Why are you more supportive of reparations for African Americans?

I’m certainly in favor of the reparations that were paid to Jews, to the State of Israel and to the Soviet Union. I wasn’t in favor of the way that it was done initially in the first few decades after the war, because it went along with the refusal to discuss the war and any questions of guilt or atonement. I am in favor of it here as part of a general attempt to look at the ways in which America has told itself that it’s an innocent country. I think that view is changing now. Reparations would only be meaningful if they were more than a check, if they were accompanied by the kind of national discussion we saw when a House subcommittee discussed a reparations bill in a hearing in June.

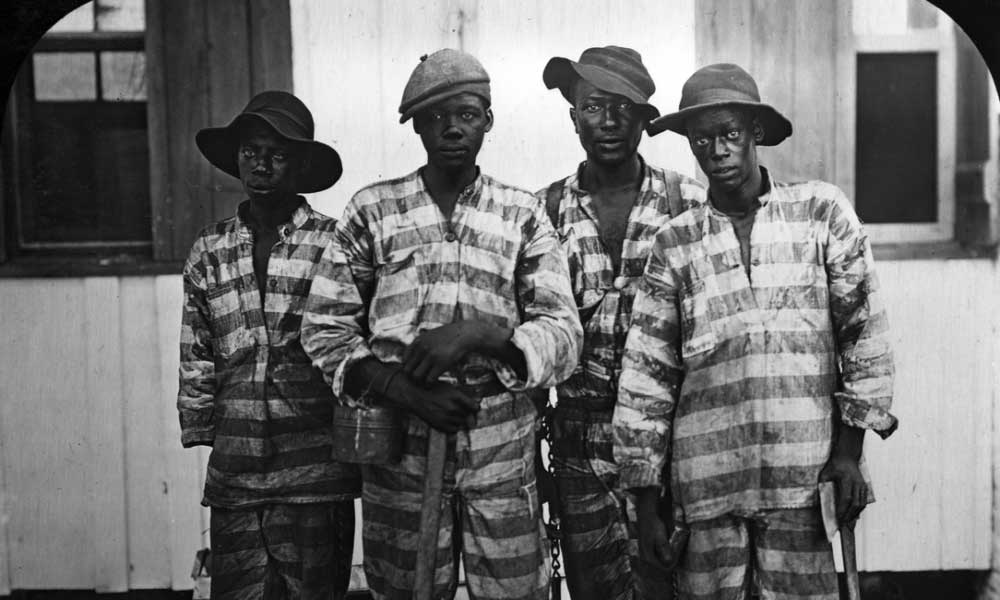

Actually, African Americans were promised reparations by General Sherman in 1865—the idea of “forty acres and a mule.” As soon as Lincoln was assassinated and President Andrew Johnson reinstated all of the Confederate officers, the land was literally taken back. A book that really impressed me was Douglas Blackmon’s Slavery by Another Name, in which he talks about convict leasing, which in many ways was worse than chattel slavery. I think most black Americans know something about this history, largely because it affected their families, but white Americans do not. So the question is often asked, “Well, other immigrants got their act together, why haven’t American black people been able to do that?” And I think the question is much easier to answer if you know about a host of things that were not just personal prejudice but were enshrined in law.

In your book, you describe a few times when you either tell a German that you are comparing the working through of the Nazi past to American slavery, or you tell a Mississippian that you are comparing his or her state’s history to that of Nazi Germany. Could you talk about the reactions you got to the comparison?

Well, the Germans in some sense prove my case, because nearly every German laughs when they hear the title. “What are you working on, Susan?” “Oh, I’m working on a book called Learning from the Germans.” Someone I know, a former minister of culture, started shouting at me in an Italian restaurant. He said, “You can’t publish a book with that name!” And the general line here, among “good” Germans, is “We did too little and too late and we shouldn’t be an example of anything.”

I found that very telling, because I did begin the book by talking about how hard it was and actually how bad it was in the first few decades after the war. And that affected the people I was speaking with in Mississippi very positively, because their view of the Holocaust was, as it is treated in the United States, that it’s just kind of a mystery, the devil incarnate, and the minute it was over every German must have bowed their heads in shame and said, “Oh God, what can I do to atone for this?” The fact that it took many decades for Germans to come to that point was, in a funny way, helpful to people who are working for racial reconciliation in the Deep South. People doing this work are often frustrated that many white people simply don’t get it and don’t feel the need to look at our own histories. Learning that it actually took the Germans quite a lot of time and trouble to do it was something that buoyed my listeners.

In your earlier book, Slow Fire: Jewish Notes from Berlin, which is a very personal story, you relate a conversation with the German artist Dieter, your lover, who says, “Knowing you confronts me with myself, it brings up rage, it brings up sorrow. I can’t really deal openly with you without dealing openly with my parents and I don’t know how to do that.” You ask, “What do you mean?” And Dieter says, “Look, every time I see you, I think of Dachau.” That was 30 years ago. Over the years, has your Jewishness become less of an obstacle to normal social interactions?

Yes, very much so, but that is, again, because Berlin changed. I left Berlin in 1988. My oldest child was born there. I really didn’t think it would be possible to raise a Jewish child there, or even a child who wasn’t what they now call a Bio-German—somebody whose ancestors are German rather than, say, Turkish. Germany is dealing with its own immigration/assimilation questions. Twenty percent of the country has one parent who was born in another country, which is a good thing. But that was not the case in the 1980s. That encounter with Dieter was certainly telling. I had many, many others that made me think, “I don’t want to subject my child to this.”

I went back to the States and taught philosophy at Yale for six years, then I made aliyah and taught philosophy at Tel Aviv University for five years. The year the Einstein Forum was recruiting me, I made six trips to Berlin from Tel Aviv, trying to gauge the temperature. A number of things had happened since I left. There was reunification. Most importantly for me, there was a progressive government which really had sworn to face up to the past in all kinds of ways that weren’t superficial. One was to change the “blood and soil” law giving German citizenship to people who could prove they had German blood. Berlin had become the capital and a much more international city. You’ve probably noticed, if you’ve been there recently, you can hear virtually every language and see a much more diverse number of people, not simply on the streets, but working in culture, working in journalism. There are television presenters who are not blond and blue-eyed. All of that convinced me that this actually was a place where I and my children could live comfortably.

You acknowledge in the book that the Germans are teaching a population to take responsibility for the crimes of the Nazis—in some cases, Germans who have very little, if any, biological connection to the people who were there. These aren’t the grandchildren of SS officers, these are the grandchildren of Kurdish peasants. We have the same issue in this country. Do we ultimately all assume responsibility for the historical crimes of our countries, even if we can honestly look in the mirror and say I came to this country precisely because it’s not like that anymore?

I think we are telling citizens, “If you are going to accept and be proud of the achievements of a country, you also have to be prepared to pay its debts.” When talking about monuments, I think it’s very important that we not only remember the crimes that have been committed in American history, but that we also remember the resistance and the heroism of people like Goodman, Chaney and Schwerner. There are so many heroes. Germans feel quite nervous about the idea of the hero because they feel that it was so abused by the Nazis. I say, “Look, we have a concept of ‘the other America’ that started with people like Emerson and Thoreau.” I’ve seen footage of Harry Belafonte actually speaking in East Berlin at the Palace of the Republic, saying, “I bring you greetings from the other America.” It’s very important that we not simply beat our breasts. Monuments are neither about history, nor about hate, nor simply about heritage—those are the slogans that you hear in the monuments debate—they are about values. They are about what we choose to honor and what we choose to reject in our history. And my guess is there is no country in the world that doesn’t have both, that doesn’t have things it wants to cherish and to pass on to its children and things that it needs to be ashamed of and face up to.

At the beginning of the book when you describe the elements of a national narrative, you go so far as to mention that perhaps an old national anthem should be discarded, just as East Germany replaced “Deutschland Über Alles,” and that perhaps we should replace “The Star-Spangled Banner” with a less bellicose song. I worry that you are playing with things that masses of Americans take comfort in as expressions of their love of country, and that a majority of Americans would say, “I don’t recognize my country anymore. I’m voting you guys out at the next opportunity.”

My own suggestion in the book was Paul Robeson’s “Ballad for Americans,” Paul Robeson being one of my heroes and part of the “other America.” That song was recorded in 1939, and it was played at the 1940 Democratic, Republican and Communist Party conventions. It shows you something about how our history can change. It’s probably too cheesy and over the top for today’s ears.

It’s not the merits of the Robeson song that I question. It’s the substitution of it for our very imperfect national anthem—which gets crazier in the later verses, actually—in a way that is unsettling to people who may never read Hannah Arendt but who have a sense of their country that they cherish. I felt “There goes Ohio” as I was reading it.

Well, I don’t know about you, but when in 2007 I became a passionate supporter of Barack Obama, my New York journalist friends said I’d been in Europe too long and only a European could believe that an African American intellectual could become president of the United States. It seemed pretty impossible to a lot of people, and the backlash that we are experiencing now notwithstanding, Americans did come together, the majority of us, around the very unlikely presidency of Barack Obama. I have an open mind about what we could come together around now.

By this reasoning, Jews should claim reparations from Egypt, for they were slaves unto Pharoah.

How sad that some intellectuals see the past (or present/future) in terms of Nazism (far right) or Communism,( far left.) Is there another possibility for a leftist Jewish intellectual? My mantra for all of us is that a change of heart is what is necessary! The Judeo-Christian Bible calls it ” circumcision of the heart.” Genuine contrition and repentance are what are required, while acknowledging the existence of the God of Israel…the reason for the existence of the Jew in the first place. Slavery existed in Biblical times as a necessity for reasons of war and economics. It had nothing to do with race or ethnic differences; anyone of any race, creed, educational background or socio/economic condition was fair game for capture from the winning side. Poor people often sold their children into slavery, or they were confiscated due to debt. It was the way of life. In more recent times, the idea of ethnic superiority became a factor. Black people were portrayed in the World Book Encyclopedia as intellectually inferior to whites and ethnic cleansing is commonplace worldwide, finding its’ golden age in Nazi Germany. On a trip to Germany in 1989, my husband and I spent time with two Northern German families and one German speaking Swiss family. The couple in the northernmost city were clearly anti-Semitic, saying of them: “the world has always had troublemakers.” The other German family were humble, contrite and couldn’t speak much due to shame. The Swiss couple were quite neutral; never speaking a word about the situation. Perhaps that is still the make-up of the German state. In any case, anti-Semitism is on the rise worldwide, racism is raging still, and pretending that a political/economic change anywhere can make a difference is absurd. Again, read your Bibles. God is no respecter of people; He hates racism, ethnic cleansing, and godless societies. Choose you this day whom you will serve…even Communism has a god…and he hates all that is good and righteous.